Summer Research Program Opens Doors of Discovery for Veterinary Students

The NC State Veterinary Scholars Program is one of the strongest in the nation, offering students 10 weeks of meaningful mentorship and a stipend to dive deeply into the wide range of innovative research projects that NC State College of Veterinary Medicine faculty lead.

Many NC State veterinary students are spending this summer getting hands-on learning through internships in animal clinics or externships in equine practices, but more than 50 are working with faculty mentors on campus, knee-deep in research ranging from investigating the role of COVID in neurodegenerative diseases to using electrical pulses to try to induce a positive immune response against metastatic cancer.

Innovative research is a pillar of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, where nearly every faculty member is involved in advancing the field of veterinary medicine through investigation and discovery. Exposing students to research paths is equally important, and the college’s Veterinary Scholars Program offers DVM students a paid opportunity to pursue their research interests under faculty mentorship.

“If you look around the College of Veterinary Medicine, you’ll see many of our researchers got their start in a summer research program like VSP during vet school,” says Dr. Joshua Stern, associate dean of research. “I did, the dean did, and there’s a whole host of others. It really kicks off a career trajectory.”

NC State’s VSP program, in conjunction with the national Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program, is one of the strongest in the nation, offering students a $6,500 summer stipend so that they can afford to participate. Stern says he expects more than 40 of the students to present their findings at the national Veterinary Scholars Symposium in Minnesota in August.

Over the 10-week program, students attend weekly seminars focused on learning the research process in addition to working with their mentors and networking with other veterinarians and researchers during visits to outside research facilities. Dr. Jody Gookin, a professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences, Dr. Ronald Li, an associate professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences, and Dr. Sam Jones, Assistant Dean for Graduate Programs, collectively lead the program, whose success Gookin attributes to how approachable the faculty advisers make the often deeply scientific research.

“When people think about research in veterinary medicine, they automatically go to research around treatment and diagnosis in pets and our animal patients,” Stern says. “We do that exceptionally well, but the research portfolio of the College of Veterinary Medicine is so much broader than that.”

Our researchers and scientists, he says, are literally helping understand the very basic functional units of cells. They’re helping us understand how organisms develop. They’re helping us understand the genetics and genomics of virtually every organ system.

“And they’re working not just for animals, but for people and the planet,” he says.

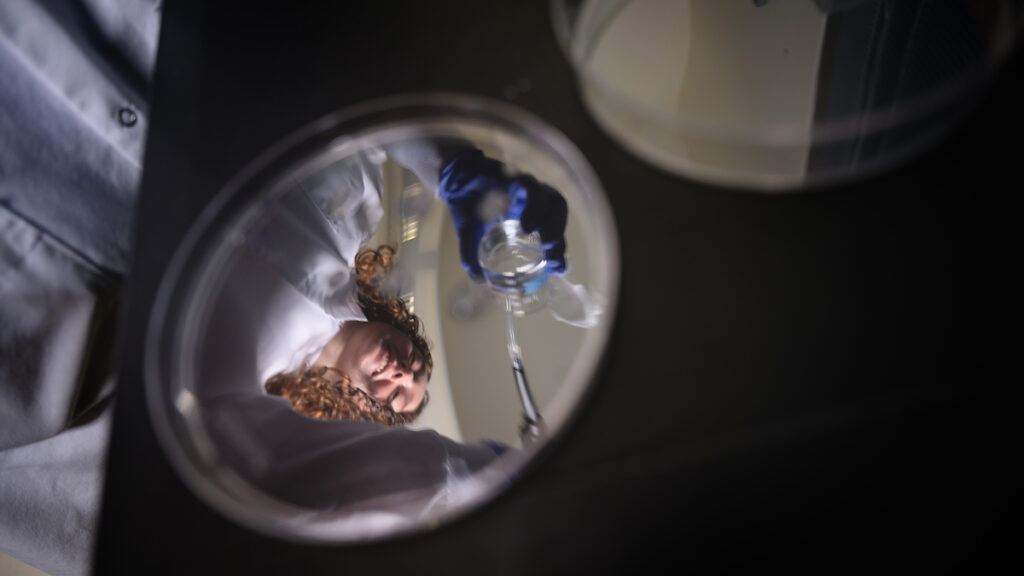

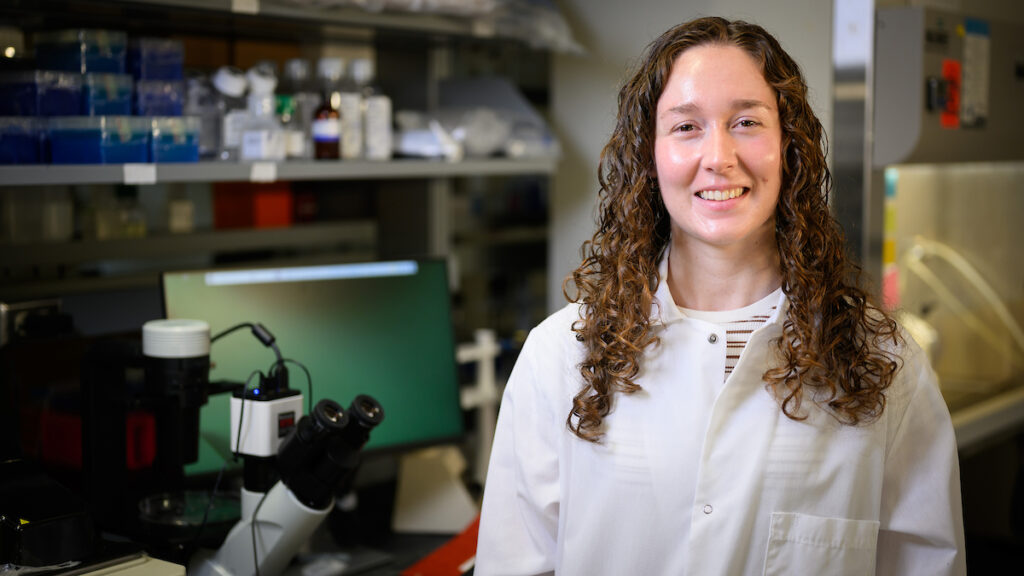

This summer, Brooke Stonemetz, NC State DVM Class of 2028, is exploring regenerative medicine with Dr. Christophe Guilluy, an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, by analyzing chromatin remodeling during freshwater polyp regeneration.

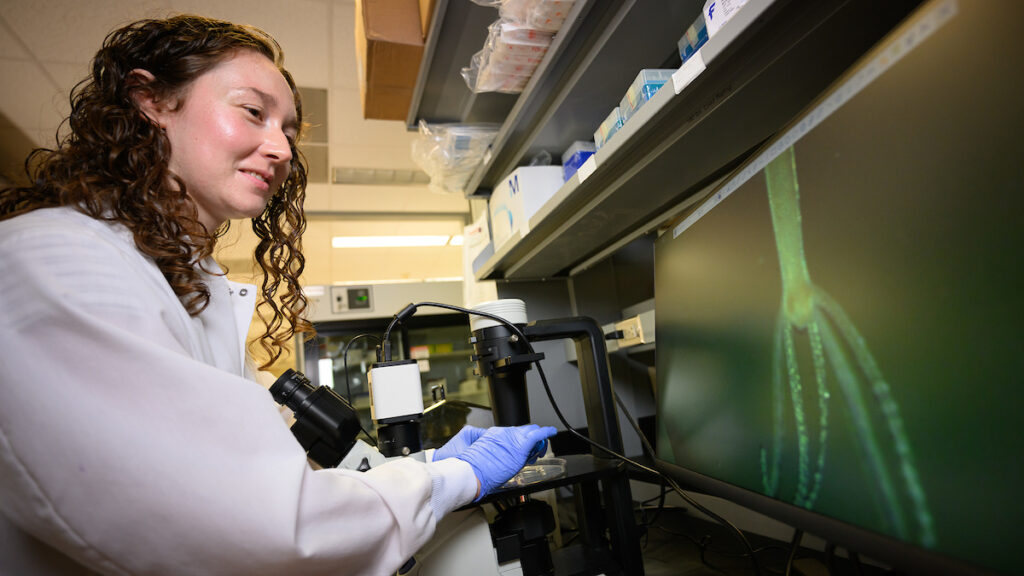

The polyps, called hydra vulgaris, can regrow their heads or a foot if they lose them.

“And if you cut them off at the same time, leaving the hydra in three parts, each part will grow into a complete hydra,” says Stonemetz, who grew up near Charlotte. “So they have a signaling pathway that tells them, ‘Do I need a head or do I need a foot?’ and we’re exploring how that happens.”

The nucleus holds all of the DNA of a cell, and the DNA is packaged in chromatin fibers, which have protein histones that play a crucial role in the organization of the DNA, she says. Dr. Guilluy’s research is looking specifically at the role of Histone H3 Lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation in influencing the behavior of Hydra vulgaris cells.

“When Histone 3 Lysine 9 becomes methylated, it silences genes, thereby preventing the DNA from being transcribed into RNA, so right now, we’re looking at, why is it present?” she says. “In his previous work, Dr. Guilluy was surprised to find the methylated protein present after the head or foot was amputated because, how is this thing regenerating if it’s not able to transcribe and access DNA?”

Dr. Guilluy describes methylation as a reversible chemical modification of the Histone 3 protein.

“This modification is a key part of the epigenetic mechanisms that cells use to control which genes are active or inactive” he says. “It’s like a chemical tag on Histone H3 that switches genes on or off without changing the DNA itself.”

Studying the hydra’s response to tissue injury could lead to uncovering the molecular “secrets” that allow them to regenerate so effectively, which would advance regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, Guilluy says.

In the lab, Stonemetz is testing how well the hydra regenerate using different inhibitors of Histone methylation and then using RNA sequencing to evaluate the downstream effects.

‘That’s the Beauty’ of the Program

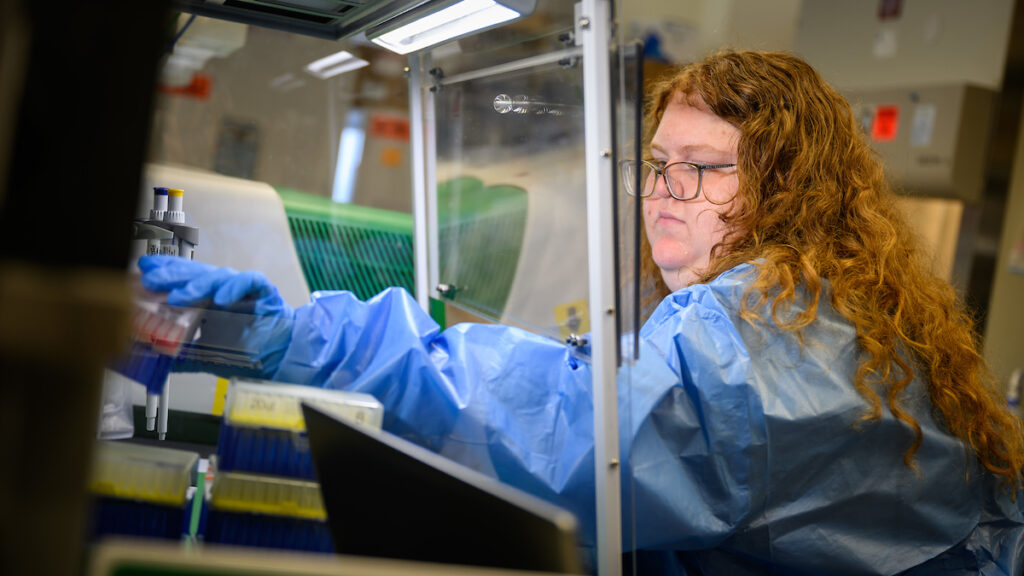

Katherine Stalford, Class of 2028, has been interested in infectious diseases since she was bitten by a dog as a child and developed MRSA osteomyelitis. This summer, she’s working with Dr. Adam Birkenheuer, the Andy Quattlebaum Distinguished Chair in Infectious Disease Research at NC State, on measuring the prevalence of vector-borne diseases in animals at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

“It’s a fantastic area for research because they have a lot different species, potentially from different continents, and they’re interacting with each other and also possibly with native North American wildlife,” says Stalford, an Asheville, North Carolina, native. “One of the big questions was, are there any vector borne diseases within this population of animals in this safari park? And if so, what are they and where are they from?”

Vector-borne diseases, such as Lyme disease and malaria, are transmitted to humans and animals through the bites of infected mosquitoes, ticks and fleas. The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is an international leader in researching vector-borne diseases.

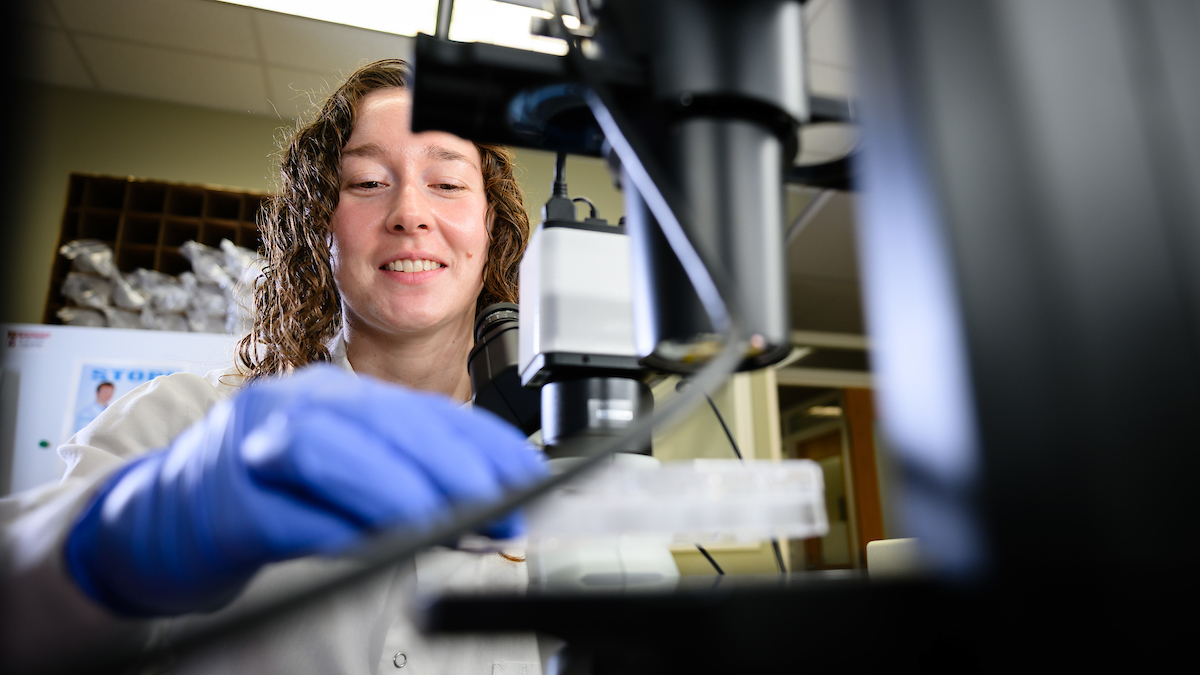

Stalford’s work includes extracting DNA from nearly 150 blood samples from about 50 animal species at the zoo and then using a polymerase chain reaction or PCR test to look for eight genera of vector-borne pathogens. Positive tests are sent out for DNA sequencing to see whether they can identify the species.

“It’s a fun mix of lab work and data analytics,” Stalford says. “It’s so fun to actually line up the sequences and see the genetic code and try to guess it. I’ve always wanted to learn, but it’s kind of hard sometimes to get the opportunity to receive that training. That’s the beauty of the VSP program.”

The work could help keep animals healthy by pinpointing the presence and transmission of vector-borne diseases and lead to biosecurity treatment protocols.

“Just being more aware of the presence and path of vector-borne diseases is important,” she says. “It’s an ever-increasing research field, especially in veterinary medicine.”

Stonemetz and Stalford, who both say they plan to focus on wildlife and exotic animal medicine, say the VSP program has been life-changing.

“It sets up a really nice framework for doing research that every week we have a seminar where we go over important things such as grant writing or literature searches,” Stalford says. “Drs. Gookin, Li and Jones are amazing and do a fantastic job of organizing it. It allows for people to come in and actually get trained, learn to ask questions. It’s a really unique program.”

Stonemetz has never participated in research before and has high praise for Guilluy.

“Every experiment that I’ve done, we’ve done a test run,” she says. “He says, ‘Let’s walk you through each step. And he always asks, are you comfortable? He’s definitely very helpful, and I think that it’s really important to have in a situation where someone hasn’t had experience in research before and is considering it.”

Two decades ago, the National Research Council warned in a report called “Critical Needs for Research in Veterinary Medicine” that too few veterinarians were going into research and that colleges should find ways to expand the field.

“Veterinary research serves as the interface of basic science and animal and human health that is critical to the advancement of our understanding of and response to impending risks and to the exploitation of disciplinary advances in the pursuit of One Medicine,” the report said. “Food safety, emerging infectious diseases, the development of new therapies, and the possibility of bioterrorism are examples of issues addressed by veterinary science that have an impact on both human and animal health.”

As Stern says, veterinary colleges like NC State are uniquely positioned to advance research in ways that improve the lives of animals and humans because they have collaborative research groups examining science at every step from bench top cellular signaling to human and veterinary patients.

“It’s an incredible breadth of research that the students are participating in at NC State,” he says. “Whether you’re in the clinic all the time, at the bench most of the time, or somewhere in between, research touches every corner of this college.”