The Human Connection

At the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, we conduct research that leads to healing across the animal-human bond. ‘Bench to bedside’ takes a unique form on our campus, where advancements bridging veterinary research and human health care can span ‘barn to bedside’ or ‘farm to table.’

By Katie Rice

Identifying gene mutations linked to bladder cancers and investigating targeted treatments. Improving storage methods to keep intestines healthy for transplant and expand the donor pool. Studying cardiac genetics to develop therapies for cardiomyopathy.

This critical research may be happening at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, but it has a direct benefit on human health, too.

“We’re taking the fundamental knowledge that we learn through research and using our expertise and resources to impact human and animal health, whether that’s in a screening mechanism, a new therapeutic or a better diagnostic tool,” says Dr. Michele Battle, head of the college’s Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences.

Whether conducted at lab benches in the state-of-the-art Research Building, in modern wards at the Veterinary Hospital or in the dynamic fields of the Teaching Animal Unit, a majority of the research happening at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is applicable to human health.

“Translational medicine is a two-way street between what we do at the bench and what we see in the clinic,” Battle says. “Many diseases we see in people also occur naturally in animals, and comparative medicine allows us to identify commonalities in diseases across species and solve problems in both animal and human health.”

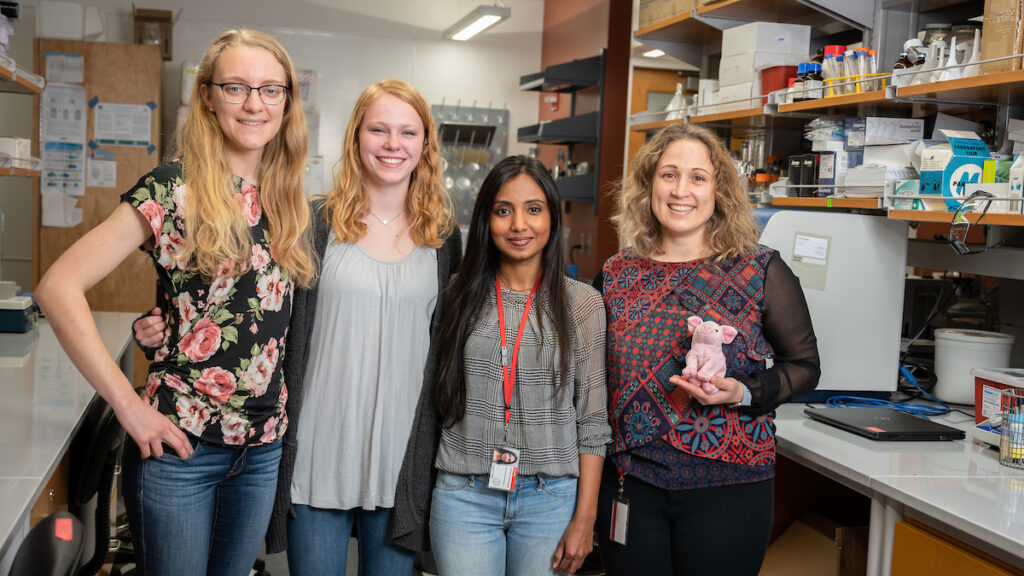

For instance, faculty and graduate students across the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences and the Department of Clinical Sciences – including Dr. Jorge Piedrahita, director of the Comparative Medicine Institute – found in 2023 that pig intestinal epithelial stem cells are similar to those within the human intestine. This groundbreaking discovery means that, by studying colorectal cancer in pigs, researchers can better understand the disease in humans, too.

Located inside the Research Triangle, the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is a neighbor to the nation’s preeminent human medical schools and major pharmaceutical and biotechnical developers, leading to unparalleled interdisciplinary collaborations on health care’s biggest needs.

From research with whole-body benefits to organ-specific investigations, the college makes a difference in the health of our animal and human communities every single day. Here’s a glimpse of recent life-changing work conducted by our faculty and graduate students.

Helping Whole-Body Health

Lung, bladder and colorectal cancers are among the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States, affecting approximately 474,000 Americans combined in 2023. Several College of Veterinary Medicine researchers have dedicated their careers to treating and one day potentially eradicating these and other types of cancers.

Dr. Ken Adler, a professor of cell biology, was the first researcher to identify the MARCKS protein’s role in lung cancer progression. Now, the cancer drug he developed to target the protein has shown encouraging results in halting the progression of advanced lung cancer in a phase 2 human clinical trial.

Studying cancer development in companion animals can give us valuable insight into human cancers because pets share our environments and are exposed to many of the same carcinogens.

Dr. Matthew Breen and Dr. Paul Hess understand this well. Breen, the Oscar J. Fletcher Distinguished Professor of Comparative Oncology Genetics, pinpointed novel genetic mutations linked to a subset of canine bladder cancers that could lead to targeted treatments in dogs and humans.

Hess, an associate professor of oncology and immunology, partnered with Dr. David Zaharoff, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at the NC State College of Engineering, to develop an immunotherapy treatment for late-stage canine muscle-invasive bladder cancer that is currently in clinical trials at NC State. Their National Institutes of Health-funded research aims to find a treatment for the same type of cancer in humans, which has been considered incurable thus far.

“Immunotherapies that succeed in dogs are ‘fast-tracked’ into humans,” Hess says. “Veterinary oncology is in a sweet spot: We get to try to help our patients and people at the same time.”

Coronaviruses have been top-of-mind for scientists and the public over the past four years, and the veterinary research field is no exception.

Assistant virology professor Dr. Elisa Crisci found that a novel platelet-rich plasma biologic drug developed at NC State not only stalled the spread of a common porcine RNA virus in cells, but it also made human RNA viruses, including coronavirus, less infectious.

Using an in vitro approach, her team found that the antiviral treatment, called BIO-PLY™, reduced the viral load of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, or PRSSV, and decreased the infectious viral particles spread in macrophages, a type of white blood cell. When tested on the human coronavirus and influenza A virus, the drug had similar outbreak-fighting effects. Crisci’s lab is developing studies to evaluate the treatment in pig patients with viral respiratory infections and pneumonia.

A key step in stopping spread is understanding how a disease moves through communities. Infectious disease professor Dr. Cristina Lanzas models disease spread in animal and human populations, and she recently tracked the impact of vaccination on COVID-19 transmission in St. Louis. Her team found that higher vaccination rates led to fewer COVID cases, adding to a body of research showing that higher vaccination rates make COVID more manageable.

NC State scientists are also advancing treatments for diseases that spread zoonotically.

Dr. Ed Breitschwerdt, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases, is considered the foremost expert on the Bartonella bacterial family. In 2023, his team discovered that Bartonella henselae, which causes cat scratch disease, could survive in fluids including blood, saline and cow’s milk for up to a week, demonstrating the bacteria’s previously undocumented ability to survive in external environments.

Bartonella infections can be serious or even life-threatening. Breitschwerdt’s lab is working with researchers from Duke Pharmacology and Tulane University to develop an antimicrobial treatment for bartonellosis that the group hopes will heal both animals and humans.

PHOTO BY JOHN JOYNER/NC STATE VETERINARY MEDICINE

Good health begins with good nutrition, and College of Veterinary Medicine researchers work closely with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration to protect the nation’s food supply from veterinary medication residues, pesticides, environmental toxins and the types of foodborne pathogens that sicken over 48 million Americans every year.

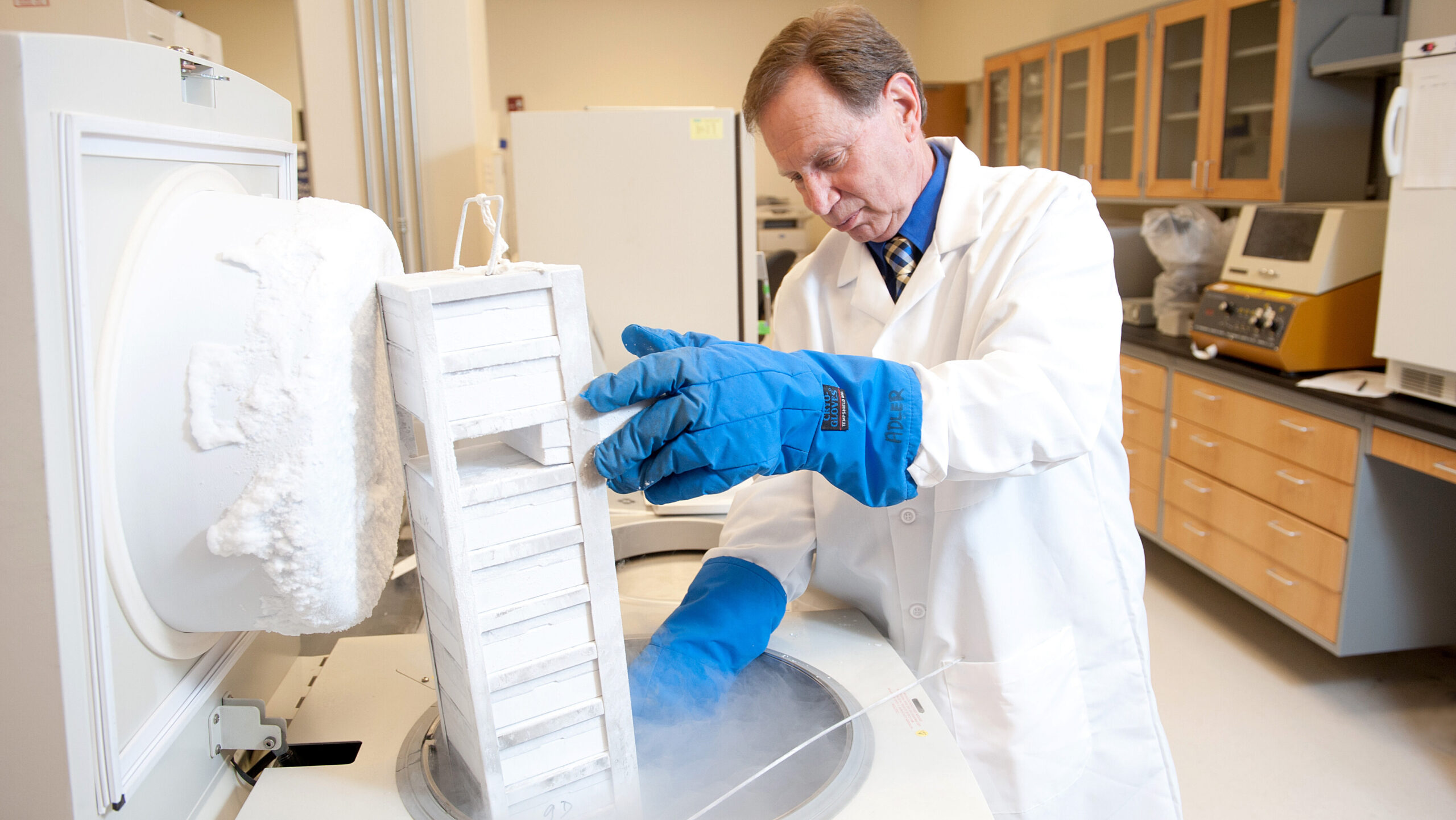

Dr. Ronald Baynes, a director of the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Databank, says the 42-year-old organization co-led by NC State maintains the most comprehensive veterinary pharmacokinetic database nationwide that veterinarians can consult in real time to mitigate drug and chemical residues from animal-derived food.

Much of the databank’s information comes from live animal and pharmacokinetic modeling research to better understand how changes in animal health status and physiology can influence how long it takes an animal’s body to process medications or recover from chemical exposure. This work is conducted by NC State scientists, including clinical veterinarian Dr. Danielle Mzyk, ruminant medicine associate professor Dr. Derek Foster and assistant professor Dr. Jennifer Halleran, along with a team of technical support staff and graduate students.

“When we publish and present our work, we’re sharing with the world that animal and human health are interconnected,” says Baynes, interim head of the Department of Population Health and Pathobiology.

Faculty within the department extensively study antimicrobial resistance, which can lead to the proliferation of disease-causing agents in our food, animals and environments. Dr. Sid Thakur, executive director of the university-wide Global One Health Academy, veterinary microbiology professor Dr. Megan Jacob and Global Health Program director Dr. Paula Cray are key partners with the Food and Drug Administration, leading grants within the organization’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System and GenomeTrakr project, which helps identify drug-resistant pathogen strains across the globe.

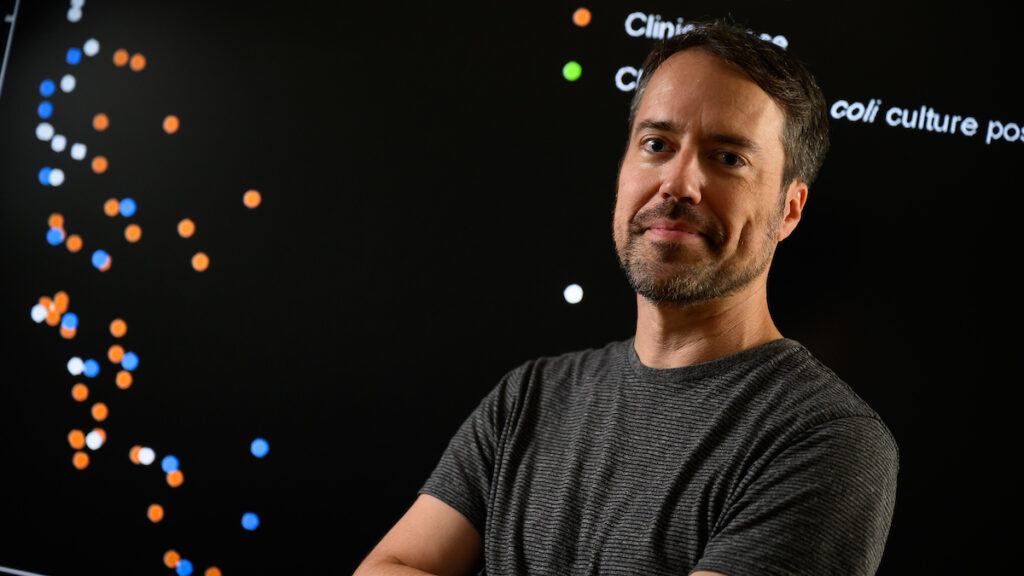

In a recent project, the group tested for E. coli in meat sold at grocery stores statewide, found evidence of multidrug-resistant E. coli in a significant share of the meat tested and isolated an emerging E. coli strain in some samples. This research showed the need for additional studies on the origins of drug resistance and further monitoring of a new pathogen.

Earlier this year, a team including Thakur and Dr. Ben Callahan, an associate professor of microbiomes and complex microbial communities, developed a new computational technology to serotype, or classify, E. coli and Salmonella enterica by sequencing a single-marker gene. Their work is a key steppingstone in improving and expediting the detection of foodborne pathogens and avoiding illness outbreaks.

Boosting Body Systems

The nervous system is the body’s control center and includes the brain, spinal cord and an extensive nerve network. College of Veterinary Medicine researchers work with it all.

Dr. Natasha Olby, the Dr. Kady M. Gjessing and Rahna M. Davidson Distinguished Chair in Gerontology, is deepening medicine’s understanding of human aging by studying the process in dogs. Her research has demonstrated that aging dogs and people share the same relationships between hearing loss, sleep disruption and dementia.

Olby’s comparative research also includes identifying similarities in gene mutations that cause neurodegenerative and muscle diseases in dogs and people. She helped uncover a gene mutation in canine degenerative myelopathy — a condition comparable to Lou Gehrig’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, in people — and is currently running clinical trials at NC State evaluating a targeted gene therapy for the condition.

Dr. Santosh Mishra, an associate professor of neuroscience, is also making headway in neurosensory research through his investigations of common chronic skin and joint conditions. Last year, Mishra identified the brain natriuretic peptide’s role in activating atopic dermatitis, also known as eczema. This finding suggests that blocking the peptide’s ability to bind to skin cell receptors could lead to future eczema therapeutics.

The immune system directs the body’s response to bacteria, viruses and other pathogens and includes the thymus, spleen, lymph nodes, white blood cells and bone marrow. Such a complex system demands collaborative research.

Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening severe allergic reaction that can sometimes occur idiopathically, without being triggered by a known allergen. Traditional immunotherapies to prevent recurrent anaphylaxis can be prolonged and ineffective, so associate immunology professor Dr. Glenn Cruse is testing the ability of a longer-term gene therapy treatment called KitStop to decrease anaphylaxis’ severity.

The new therapy depopulates mast cells, a kind of immune cell found in connective tissues that causes anaphylaxis. Cruse’s lab found KitStop decreased the duration and severity of anaphylaxis in a mouse model and proposed it could be an effective therapy for people who regularly experience anaphylaxis.

Our immune systems also respond to chemicals in our environment, including PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Dr. Jeff Yoder, a professor of innate immunology, and Dr. Katie Sheats, an associate professor of equine primary care, found that three common PFAS inhibited an immune process called the respiratory burst that kills pathogens and fights infection.

Their study is the first to link these PFAS, part of a family of “forever chemicals,” to suppressed function of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. It also established new cellular screening tools that future researchers could use to identify chemicals with immune-inhibiting effects.

College of Veterinary Medicine faculty are experts in the myriad conditions affecting the skeleton, muscles and connective tissues.

Dr. Duncan Lascelles, the Dr. J. McNeely and Lynne K. DuBose Distinguished Professor in Musculoskeletal Health, leads the field in cross-species pain research through his Comparative Pain Research and Education Centre and Translational Research in Pain program. His labs frequently partner with researchers college-wide and beyond to develop methods to measure and treat pain in different animal species.

Lascelles’ recent collaborations include a partnership with Duke University researchers investigating the ability of a localized adenosine solution to relieve pain and promote healing after bone injury. That study found that giving adenosine, a naturally occurring chemical in the body, to mice with tibial fractures reduced pain for these mice and improved their bone healing.

With further research, adenosine could replace nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioid analgesics, both of which can have significant side effects, to alleviate bone fracture pain in human orthopedic patients.

Dr. Lauren Schnabel, a professor of equine orthopedic surgery, conducts research that can also benefit other species with musculoskeletal injuries and diseases. Her work includes pioneering the use of equine mesenchymal stem cells from the bone marrow in therapies to treat tendon and ligament injuries in horses. The same treatment will likely promote healing in humans and dogs with Achilles and other tendon injuries.

Diastolic dysfunction, a common type of failure in the heart’s lower chambers, often occurs with age in humans and is more prevalent in women than in men. Rhesus macaques also develop the condition, but until recently, scientists did not know whether their disease patterns were similar.

Assistant clinical professor Dr. Yu Ueda found that a macaque’s age and exercise levels could predict its risk for developing diastolic dysfunction and that female macaques showed increased risk. His research opens the door to further efforts to prevent and treat diastolic dysfunction and similar cardiovascular diseases in primates and humans.

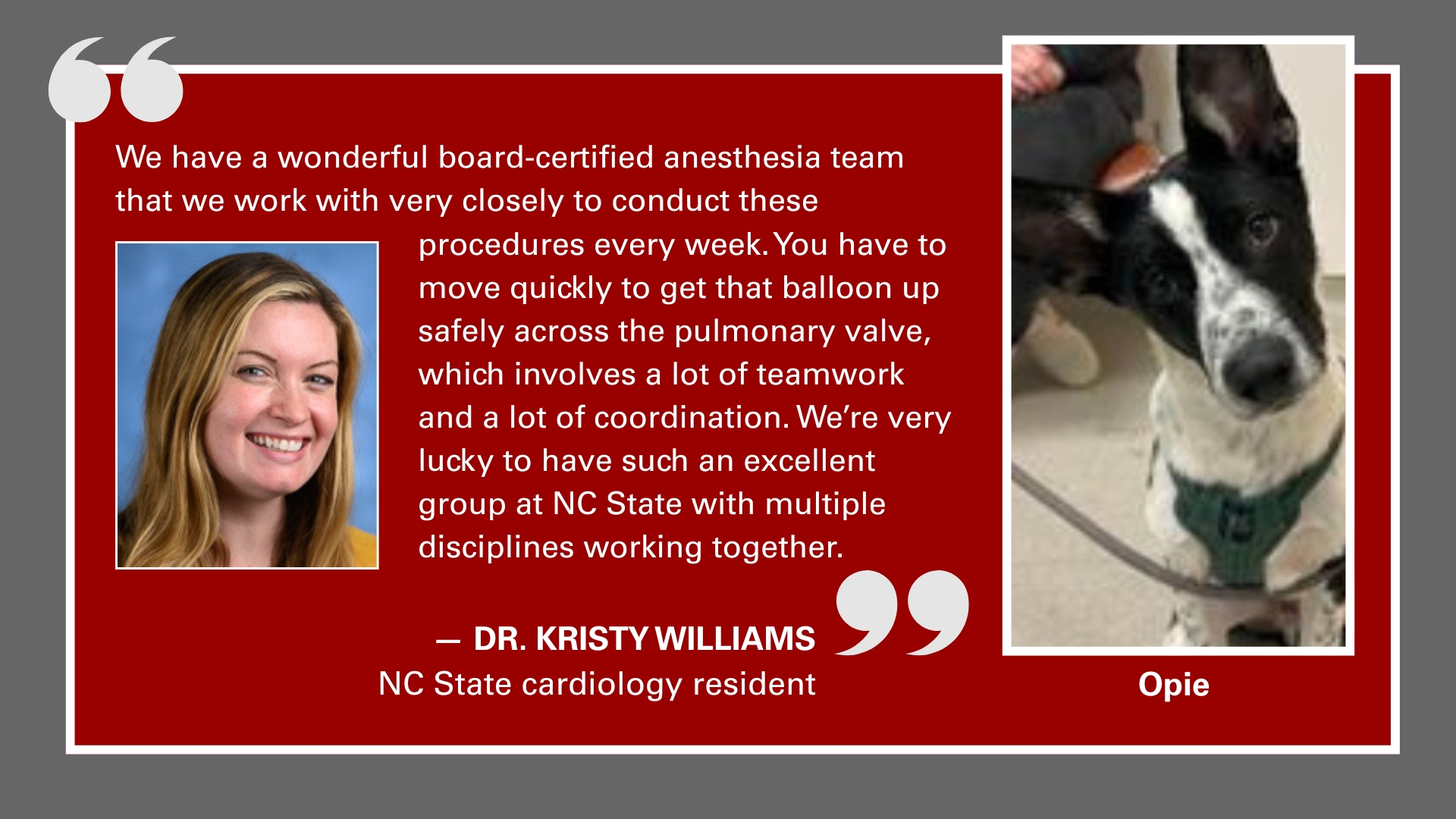

Ueda’s co-author on the study is Dr. Josh Stern, associate dean of research. Stern’s lab consistently highlights the parallels between animal and human cardiac conditions, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Subvalvular aortic stenosis is another highly comparative condition. It is the most common congenital heart disease in dogs, and though rarer in human children, it produces a similar fibrous ridge under the aortic valve that obstructs blood flow from the heart’s left ventricle.

Stern’s analysis showed that treatment diverges between species as the disease progresses, with medications prescribed for canine treatment and surgery advised in human care. He noted that veterinary and human cardiologists should work together to find treatments to halt disease progression and identify a method to permanently remove the ridge. The Stern lab is currently leading a clinical trial for dogs with severe subvalvular aortic stenosis that Stern hopes will help children with the same condition.

College of Veterinary Medicine researchers help animal and human communities breathe easy about health, especially when it comes to the lungs.

Dr. Yogesh Saini, a professor of pulmonary immunology, researches the respiratory tract, including the impact of environmental toxins on the lungs. Saini collaborated with researchers at the University of Texas at Tyler Health Science Center on work suggesting that a specific peptide, CSP7, could be an effective treatment for conditions including cigarette smoke-induced lung injury and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD.

COPD is a leading cause of death in the U.S. and worldwide. Many current treatments reduce airway inflammation or manage COPD’s symptoms, but CSP7 may be able to reverse lung injury while improving the organ’s function, making it a more effective therapy. The research team is also furthering its preclinical testing of this peptide against allergic asthma.

Additionally, NC State scientists are looking to the lungs to improve drug delivery methods. Researchers from the College of Veterinary Medicine and College of Engineering collaboratively developed a tunable nebulization system to more effectively administer intrapulmonary drugs, which can work faster and at lower doses than medications given in other ways.

The team, including Cruse and former regenerative medicine professor Dr. Ke Cheng, found that the system, which allows patients to inhale medicine liquefied into a fine mist, was effective in mice and could be upscaled for larger species.

The College of Veterinary Medicine’s gastrointestinal experts are guiding the field in understanding and treating conditions of the stomach, intestines, gallbladder and related organs.

Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff, is a bacterium that causes nearly half a million infections in people in the U.S. each year. Infections can result in colonic inflammation with potentially life-threatening symptoms.

Dr. Casey Theriot, an associate professor of infectious disease, launched a study that discovered that certain bile salt hydrolase enzymes found in different Lactobacillus bacteria can restrict C. diff’s spread within the gut. Her team’s work reveals how altering the gut bile acid pool might be an effective treatment for patients with C. diff infection, avoiding antibiotics that can exacerbate the infection and treatments that can pose complications.

Intestinal malrotation, a congenital condition where parts of the intestine become twisted, occurs in approximately one out of every 500 births in the U.S. Its cause is unknown, but Dr. Nanette Nascone-Yoder is looking for answers.

Nascone-Yoder, a professor of developmental biology, worked on a study to identify potential environmental causes of the condition in frogs, finding that exposure to the herbicide atrazine was correlated to amphibian intestinal malrotation. It is unclear whether herbicides may also contribute to the condition in people, but her research suggests that the cellular processes disturbed by atrazine may also underlie human malrotation.

‘One Health’ At Home and Abroad

PHOTOS BY JOHN JOYNER / NC State Veterinary Medicine

All of this work, combined with NC State’s exemplary research facilities, makes it no surprise that public health agencies, including the World Health Organization, rely on NC State veterinary faculty to help shape protocol. Locally, faculty also lead college- and university-wide consortiums, including the Global Health Program and Comparative Medicine Institute, to advance medical understanding using a One Health approach.

Sometimes, the veterinary college advances research simply by opening avenues of communication with human-focused scientists who are unaware of veterinary medicine breakthroughs, says Dr. Mike Nolan, interim head of the Department of Clinical Sciences.

“We help scientists in other departments, at other universities and in other health professions understand what the needs are in veterinary medicine, what we have to offer, where there are similarities and differences between human and animal health and how those can be leveraged,” he says.

These conversations have saved years and millions of dollars in research and development, Nolan says, through insight only a veterinary school can provide.

“We bring a lot of value to the region in that way,” he says.

The College of Veterinary Medicine’s renown as a prominent research institution helps recruit world-class faculty, staff and graduate students who develop new ideas that advance human and animal health. And in return, these investigators — particularly student trainees — grow professionally and personally.

Even students who enter the college without research backgrounds can get involved in studies that improve animal and human health via initiatives like the Veterinary Scholars Program. The 10-week summer program lets first- and second-year students work on mentored research projects in faculty labs under the guidance of faculty, graduate students and lab technicians.

“Research is about bedside in the clinic, about the benchtop in a lab, about helping the community, but research is also in our classrooms,” Stern says.

Because veterinary medicine researchers are well-positioned to approach health questions from a holistic perspective, they have a deep understanding of the interplay among animal, human and environmental health and are critical to advancing this approach across the world.

“I got into veterinary medicine because I believe it’s always One Health,” Baynes says. “Animals and humans share the planet and need each other, and our researchers’ work gives the public a better understanding of that interchange while improving care across species. We’re leading the way to a healthier world.”