Working for the Wolves: Carnivore Crew Labors for a Species’ Life

“No other vet school in the entire country has an opportunity like this to see such up close and personal management of the most endangered canine in the world."

Over her three years as a student at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, Annie Gorges has made the trek to the red wolf pens hundreds of times to measure out food, tote 5-gallon buckets of water and check for fallen trees, all in pursuit of protecting the world’s most endangered canid.

The wolves at NC State, which has cared for 18 animals over the past 20 years, are part of a national program to repopulate the species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service leads the effort in accordance with the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Species Survival Plan.

The Wolfpack’s wolfpack currently has four members: Oak, Niko, Boone and Brevard. Another two wolves, a breeding pair, recently went through the wildlife service’s release process on the North Carolina coast, the only place in the world that red wolves can be found in the wild.

“It’s actually very profound,” says Affrika Sanford, also in her third year at CVM and part of the student-run Carnivore Conservation Crew of wolf watchers. “Finally hearing that some are going to be released, I’m like, ‘Oh, I took care of this wolf for the last two years, and they’re suitable enough to help repopulate this species.’ We as a team work together, and this animal is thriving and is healthy enough to be on its own now. It’s very rewarding.”

The Carnivore Conservation Crew has about 50 members who are required to take at least two husbandry shifts a month, says Gorges, co-president of the crew. Each week a team captain organizes students into two daily shifts, one in the morning and one in the afternoon before dark. The afternoon team often has two members so that one can go into the pens and clean the grounds, food bowls and water buckets.

“No other vet school in the entire country has an opportunity like this to see such up close and personal management of the most endangered canine in the world,” Gorges says. “This is a once in a lifetime opportunity for students. It’s an experience most people don’t get in their lives let alone while they’re a vet student.”

A real team effort

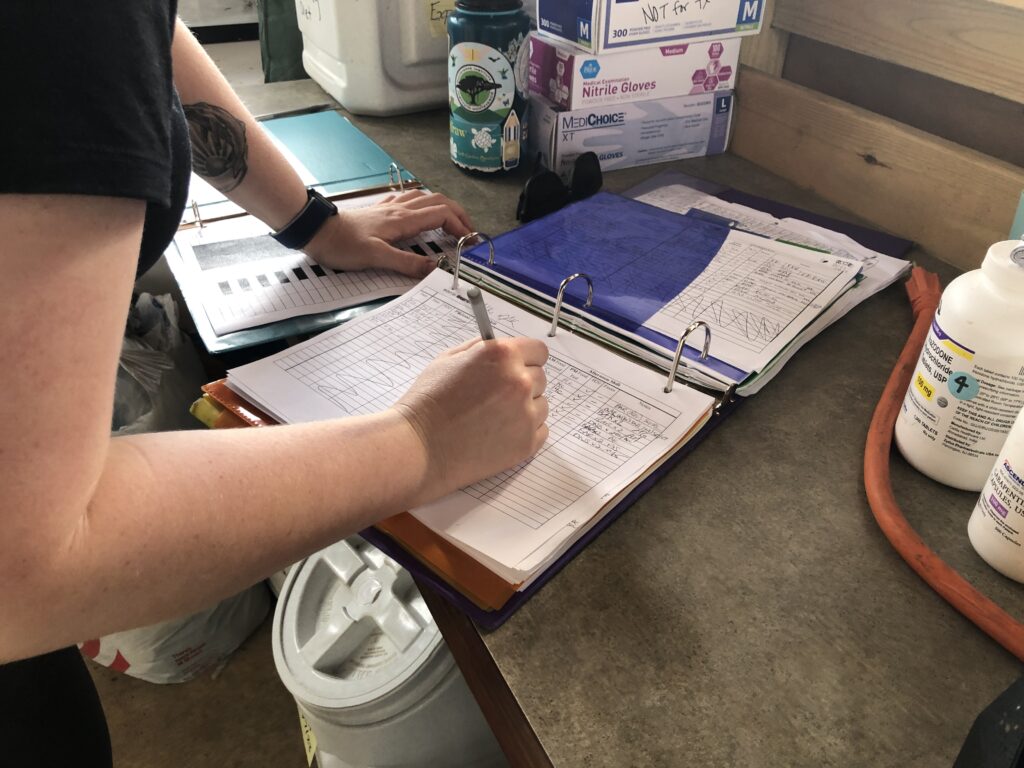

In addition to dispensing food and water, the crew’s responsibilities include walking the perimeter, checking the fences, administering medicines, keeping log books – how much food was eaten, how did the wolf look – and offering the animals activities that keep them from becoming bored.

“We try to give them something different multiple times a week,” Gorges says. “Sometimes that’s paper animals or different foods, or we’ll scatter the food so they have to hunt for it. We give them frozen items like blueberries. We put spices in ice cubes or applesauce or meat broth.”

The Carnivore Conservation Crew has several subgroups, including one responsible for planning the enrichment items. Other groups take care of preventative medicine, grounds maintenance and fundraising and merchandise sales to support the effort.

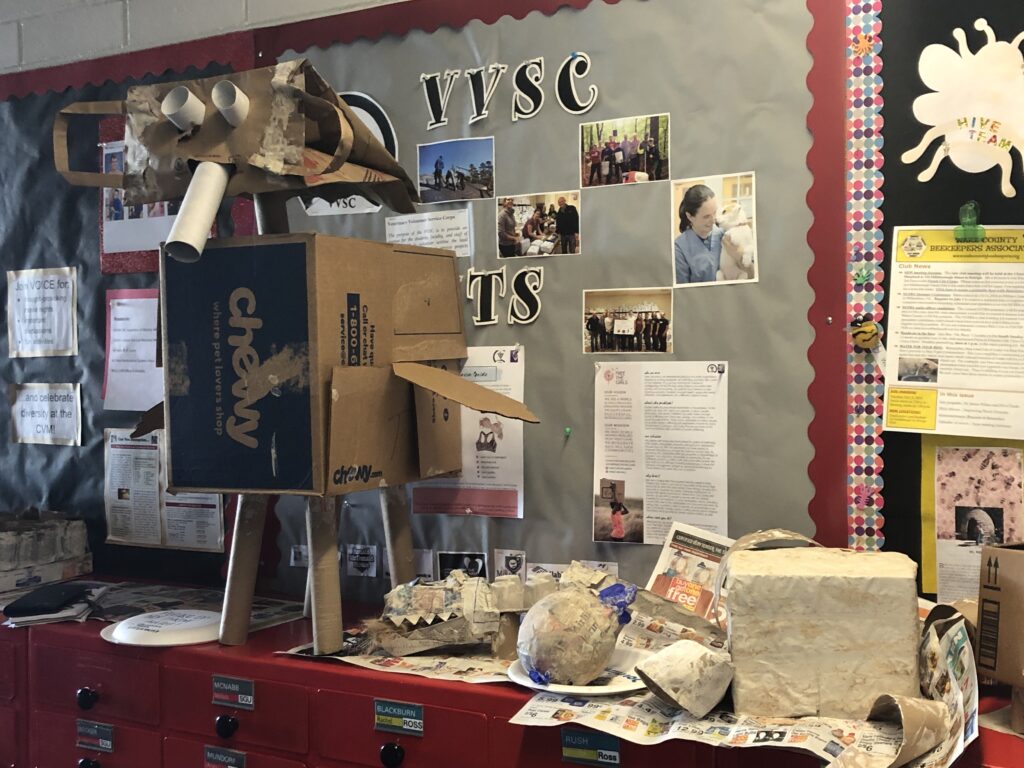

This spring, the enrichment team created critters out of cardboard, egg cartons and empty toilet paper rolls and then voted on the best creation. Boone, who turned 7 in March, later received the “giraffe,” which he dragged around his pen for days, Gorges says.

“He completely destroyed it, tearing all of the tubes off the box,” she says. “It’s just so important for their mental health.”

In the fall, the students toss pumpkins into the pens and in the winter Christmas trees. Even scent enrichment is important, Gorges says.

More than food and water

During an afternoon shift at the pens in late March, the now-brown evergreens pepper the pens, still releasing their piney odor.

Gorges has measured out dog kibble and canned food for the four resident wolves and gotten thawed whole prey ready for a fifth wolf, which was injured in the wild and brought by the wildlife service to the NC State Veterinary Hospital for surgery and care. The wild wolf, one of fewer than 20 left in the world, likely will stay in Raleigh eight weeks before the wildlife service restarts its release process for him.

“Partnerships with organizations such as the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine are an essential component of the recovery and conservation of red wolves,” says Joe Madison, program manager for the wildlife service’s Red Wolf Recovery Program. “The service is both lucky and grateful that such an organization and the individuals associated with it exist and are so willing to assist at a moment’s notice.”

Two days of rain have left the NC State wolf area soggy. Gorges, carrying five food servings in a bucket, fills up another at the water pump and then sets it down to unlock the second of three gates protecting the wolves.

At each pen, she checks the fence before feeding and watering the wolves. At one, she kneels in the mud and scoops food into the pen one spoonful at a time. At another, she takes the food and flings it over the fence in several handfuls, giving Oak and Niko, a breeding pair living together, something to hunt for later.

Scouting the fence line, Gorges finds a tree has fallen onto the back side of an empty pen. She marches inside and wrestles the branches to the ground and then over the fence.

“As far as maintenance, we do everything ourselves,” says Gorges, a California native who hopes to practice aquatic medicine when she graduates. “When dirt erodes around the fences, we’re in here with shovels. I’ve gotten a lot of handy experience.”

As her shift winds down, Gorges washes the food containers before writing down what she has seen on her rounds. She creates a log page for the wild wolf, which was released to a pen to recuperate that morning, labels his medicines and separates thawing meat into portions for the week.

“When we have wild wolves come in, we’re best equipped to deal with it, to rehabilitate them or deal with their injuries,” Gorges says. “We have the most amazing surgeons and anesthetists and just all of the exotic animal faculty and residents in the whole country, so this really reminds us of how well-equipped we are to make the most difference for this species.”

Tomorrow morning, another NC State student working to keep the red wolf from extinction will come.

Follow the Carnivore Conservation Crew on Facebook @carnivoreconservationcrew and on Instagram at @carnivoreconservationcrew.

YOU CAN HELP!

Donate to help NC State care for its Wolfpack wolf pack here.

- Categories: