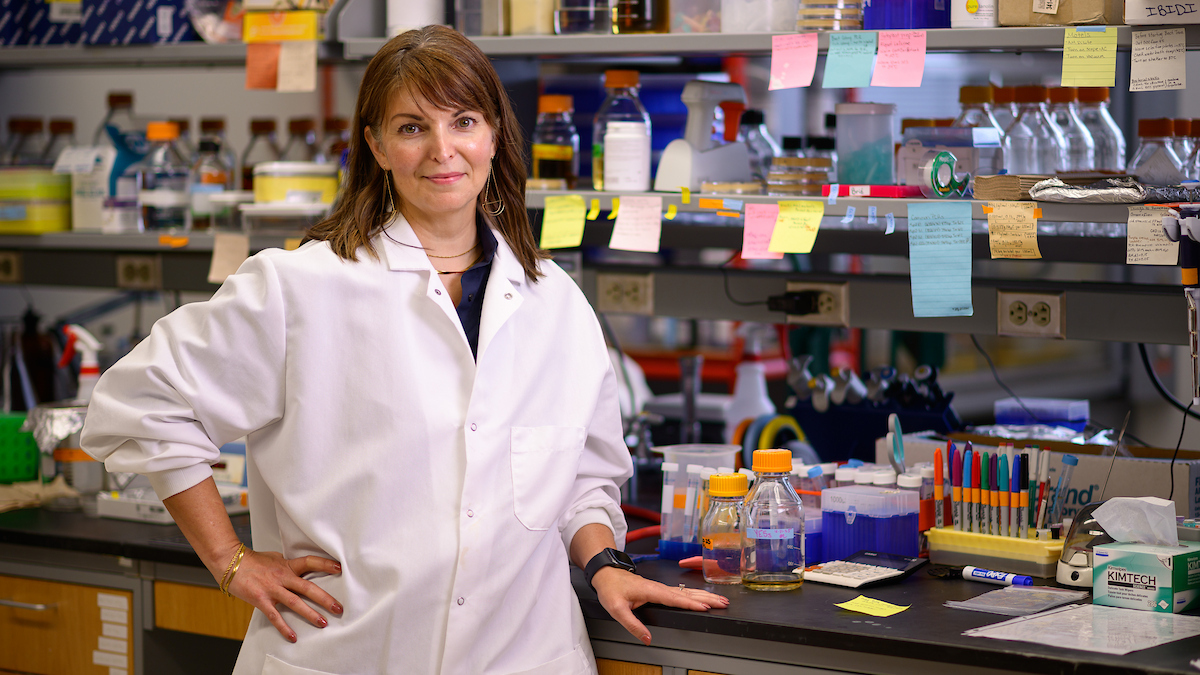

Extraordinary Purpose: Taking the Fear Out of Cancer

To know Joanne Intile is to know her cats.

First of all, there’s five of them. But the real insight into Intile’s offbeat personality is gleaned from her pets’ names. There’s Sepsis — “Sepsi” for short — a tongue-in-cheek reference to her veterinary career. There’s Crab Cake and Prunewich, both nods to her time spent working at a practice in Maryland.

(For those terrified, a Prunewich is a type of breakfast sandwich found in Ocean City, Md. Prunes are not involved.)

And then there’s the most recent addition to her feline brood. On the same day she got the job offer from the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine as the clinical assistant professor of medical oncology at the Veterinary Hospital, Intile began fostering a 3-week-old sickly cat she later adopted. She named the kitten Rally in celebration of the new position.

“Rally” is how the Long Island, N.Y., native has always pronounced “Raleigh.” The name also reflected Intile’s hope that the cat would rally back to good health — and she did under her care.

Intile earned her DVM from Cornell University, followed by an internship at Long Island Veterinary Specialists and a residency in medical oncology back at Cornell. Her appointment at the CVM comes after stints in private practices.

She’s also a veterinary journalist with a focus on materials geared toward owners of pets with cancer. Intile, who lives in Cary with her husband, Marc Hirshenson, a veterinary surgeon with a private practice in Durham, talked to us about her interesting road to specializing in oncology, her passion for writing about veterinary medicine and more.

What was your first day here like for you?

I distinctly remember just how excited I was. I parked my car and I immediately started to walk over and took 4,000 pictures of the school. I remember how proud I felt, but also humbled by the responsibility. At the same time, I just remember taking the pictures and thinking, OK, this is super-cheesy but I’m really excited.

What led you here?

Teaching is always something I’ve loved to do. A draw was definitely the school’s reputation and the oncology program’s reputation. There’s the fact that we’re doing bone marrow transplants and cutting-edge research. And we’re very open to clinical trials here, which is really important to me.

How would you describe yourself as a teacher?

I am someone who will always try to temper whatever subject we’re talking about with a practical aspect. I would tell a resident or intern that you can run every test in the book, but when you get out there in the field here are the things you’re going to have to consider for a particular case. I would ask them what would be the top two things you would recommend to that owner, because clients are going to tell you this and that. I’m pragmatic in the case approach, but I’ve also become more flexible. It’s also important to teach them that OK, you can do it that way but you could also do it this way.’

Was there an instructor who had a big impact on how you teach?

Absolutely. My mentor during my residency, Ken Rassnick, was such a huge influence. One of the things he used to always say to me was, ‘You have to decide what kind of oncologist you want to be.’

And that type of thing is so daunting when you’re starting out. You feel like that puts such pressure on you, but that really shaped how I approached everything that I have done professionally. When I make decisions I think about him saying that to me.

What led you to oncology?

I didn’t decide on oncology until I started my internship following graduation from veterinary school. I worked with an amazing oncologist at the time and I fell in love with it. It was such the opposite of what I thought. Owners come to an oncologist and you give them hope.

I decided to try my hand at applying for a residency. Most people who apply for residencies know their path much earlier on. There I was, three to four weeks before I needed to put together an application for a residency and I decided to go for it.

So for you it came down to choosing to focus on the hope of treatment versus focusing on the mentally consuming fact that they have cancer?

It came down to really realizing that once you get past that hurdle of telling an owner their pet has cancer you’re getting them to come in to find out what kind of options they have. You’re telling them it doesn’t have to be a death sentence. It can be tailored to whatever you and your pet need. And we will make your pet feel better, we will improve the quality of life and we’ll give you more time with them.

So how do you personally approach client communication, especially with people coming in for the first time to see you and maybe they’re scared or worried?

That’s a really hard question. I’ve had plenty of consults where an owner has come in and said, I’m not going to do chemo. I’m not going to do radiation. But they kind of just want information. A lot of people want to know what to expect as the disease progresses. So when I get that sense from somebody, it’s not my job to sell them on any type of treatment plan. I’m not here to say you’re a bad person because you don’t what to do this.

And then you’ll get the opposite end. You’ll get the people that say, do whatever you have to do to save my dog’s life. Most people are in the middle. They say, I got this diagnosis. I don’t know what to expect. What can I do?

What happens is you get experience over that time and you tell them here’s what I’ve seen happen or this is what I think will happen. You just have to be honest with people. You have to empower them to decide what works for them.

I think it’s also difficult for someone outside of veterinary medicine to really get an idea of what it feels like to be in your kind of position. Is there a way you can describe it?

(laughs) Yeah, when people ask me what I do for a living, I usually always hear, oooh … that must be really hard.

Well, it is hard.

It is hard and I get that. One of my main goals through my writing and the education that I do is to take that mystery out of veterinary oncology and make it less scary and make it something that’s more approachable to people.

I’m curious about your work to dispel myths and clear up misconceptions about oncology. You do that in a very public, personal way through your blog, Growth Factors. When did that start?

That started sort of fortuitously through my employment with petMD, when they had approached me about writing this blog which was a weekly article that could be on anything I wanted. And initially I took a very didactic approach to it. You know, let’s talk about tumor types.

OK, so more medical journal-y?

Yes. Then I read a lot of human medical books on how doctors think and how they feel and got really interested in the emotions behind medical writing. We’re thought of as being so regimented and I’m not. I’m that weirdo. I’m a lefty in a world of righties.

So I took a little leeway with my writing for petMD. I started writing more of a personal blog. But I’m more of a consultant now with petMD; I have to keep it to the technical stuff. So that led me to use my own avenue to get the more personal writing out there.

I want to reach out to the pet owner. I think some pet owners may not even know that specialists are out there, that this could be an option for them. So that’s how I got down that avenue with my writing — just trying to reach them.

Do you think more vets should do what you do?

I think it would be great if they want to. I understand that writing is not most people’s bag. It happens to be mine; it’s just something I really like to do. I don’t even know if I’m decent at it. I think spreading the world about specialty medicine is important.

What should people keep in mind when they come to the oncology service for the first time?

On a broad scale, just understanding that coming for the appointment doesn’t mean you’re signing onto anything. You’re not saying that you’re going to put your pet through anything. Come through the door and get the information. On a smaller scale, you’re coming here and you have access to all these opinions. You will probably meet one doctor that day, but that one doctor is going to spread roots and talk to probably anywhere from two to 10 other people about your pet’s case. And even if we just collect a tiny blood sample from your dog, you’ll have these brilliant clinical pathologists looking at your dog’s blood sample. And then if there’s any question we’re going to call you and talk.

I wanted to ask you finally, and this is something I’ve been asking everybody, what do you think makes a good vet a great vet?

I think owners have appreciated in me honesty, frankness and candor. I’m not saying bluntness. I’m just saying being honest and being able to listen to what they are saying.

These are owners who may be scared and we all know what that feels like. Distill it down to its most basic level: What would you do if you were told your dog had cancer? I would be a mess. My best doctors are the ones who are honest and direct and accessible.

For more information on the NC State Veterinary Hospital’s oncology service, go here.

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine