‘My Favorite Part of NC State’s Curriculum’: Selectives Set Up CVM Students For Excellence

During a two-week mini-term after final exams, the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine’s students explore their interests within and beyond veterinary medicine through hands-on, specialized classes.

Dr. Kelley Varner, assistant clinical professor of anesthesiology, quizzes two third-year DVM students as they prepare to sedate a gelding for orthopedic surgery at NC State’s Large Animal Hospital: How do you tell if a horse is ready for anesthesia? How long does xylazine take to work?

The Equine Anesthesia students, Maya Keefer and Jessica Arnold, answer her questions as they watch a team walk the horse into the preoperative room.

“You ready?” Varner asks Arnold, who has volunteered to induce the thoroughbred. They anesthetize him together, and Keefer joins to intubate him and wheel him into surgery.

The induction process is over in minutes, but its lessons will stick with the students for much longer. This type of hands-on, experiential learning is exactly what many look forward to during their end-of-semester selectives.

Selectives are what the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine calls its short-format classes held during a two-week mini-term after final exams. The one- and two-week courses span numerous specialties within veterinary medicine and are kept small for individualized instruction.

In a nutshell, they are “laboratories of education and innovation” where first- through third-year students can explore topics of interest to them while connecting with potential mentors, says Dr. Laura Nelson, associate dean and director of Academic Affairs.

“Selectives, for the most part, are there to help students further their preparation for a desired career goal,” she says. “They provide exploration, education and enrichment and give students the opportunity to work with veterinarians in smaller groups.”

The significance of these opportunities isn’t lost on these future DVMs.

“Selectives honestly are my favorite part of NC State’s curriculum, because you can do so many things that are not covered in class,” Keefer says. “And I can ask Dr. Varner questions immediately. I can interrupt her and be like, ‘Hey, what do you mean? What’s happening?’”

“And you get to know faculty, too, that you don’t usually get one-on-one experience with,” adds Arnold.

Currently, students are required to take 12 credit hours of selectives between their first and third years, Nelson says. First-year students must take two credits of Success in Veterinary Practice, a business-oriented course, but they are free to follow their interests otherwise.

This fall, students are learning how to treat equine colic, examine and diagnose North American marine mammals, manage the clinical aspects of trap, neuter, vaccinate and return programs and much more.

Many veterinarians-in-training are also shadowing clinicians around the Veterinary Hospital to get a feel for different services, while others are taking their CVM training off-campus to intern with practices, conduct research with outside organizations or attend industry conferences.

And that’s just a snapshot of this year’s offerings. With over 70 selectives to choose from, there’s something for everyone.

From classroom to clinic

Equine Anesthesia is one of dozens of courses open to students seeking time in clinics. Selectives offering live animal and clinical experiences tend to be the most popular, Nelson says.

“Students are interested in participating in the clinical world and learning more about what happens in hospitals,” she says. “And preclinical students are always welcome in the Veterinary Hospital, but this is one way to invite them in.”

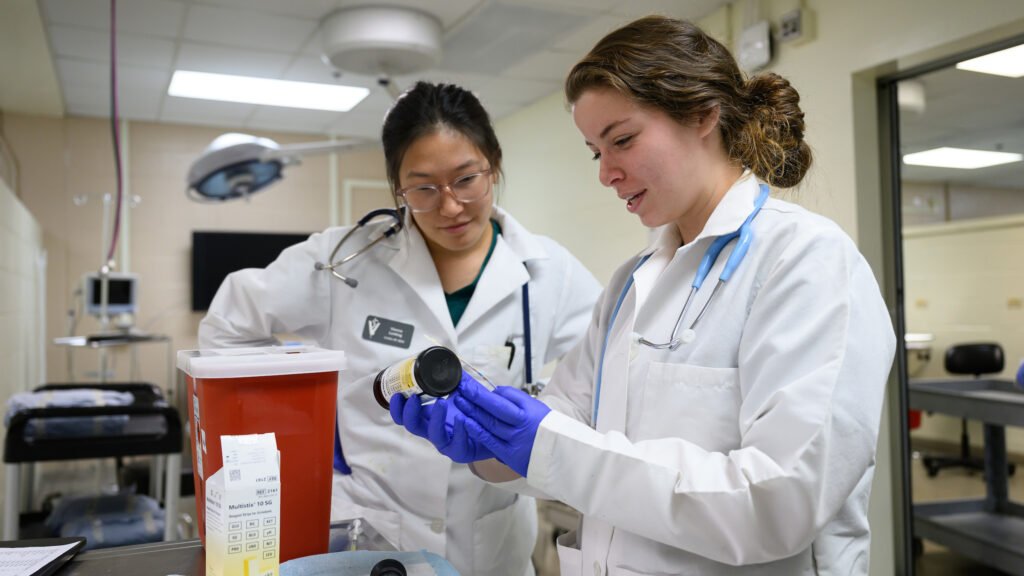

During a recent afternoon in the Advanced Ferret Medicine selective, third-year student Meghan Chung and second-year Ramya Boggavarapu rouse a ferret named after rapper Andre 3000 out of anesthesia following a physical exam.

“I’ve been waiting for all three years I’ve been in vet school to take this selective,” Chung says. “It’s so competitive to get into, and I knew it was going to be such good hands-on experience.”

Students are assigned lottery numbers for selective registration, and higher-level students enroll earlier. Boggavarapu, who is considering specializing in exotic animal medicine, says she feels lucky to have scored a seat.

“Finding opportunities to work hands-on with exotics and get supervised instruction this early is kind of rare,” she says. “And the opportunity to do surgery is great — because as second-years, we only get a chance to do a neuter. Here, we get to do neuters, spays and dental exams and learn how to use an ultrasound on a species that you don’t normally work with.”

The class, led by exotic animal medicine expert Dr. Tara Harrison, provides an overview of ferret health and treatment and also covers clinical, political and social issues unique to the mustelid species.

“I enjoy the one-on-one instruction,” Chung says. “Dr. Harrison came over and taught us how to do blood draws and was guiding us through it. It builds confidence in a way that you won’t get by just sitting in a classroom and learning about the technique.

“Plus, you get to snuggle this man,” she coos, cuddling Andre 3000.

Teaching resilience and relaxation

From application to graduation, veterinary school can be a perfectionist environment where students feel pressure to succeed, instructors say. But in a couple selectives, students are learning that it’s OK to try new things and fail.

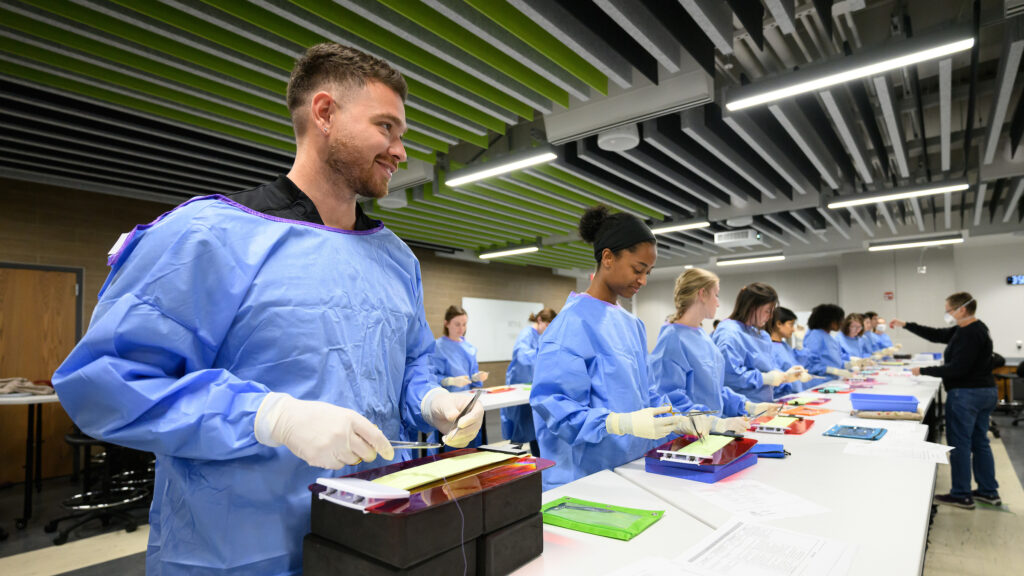

Dr. Amy Lehman and Dr. Jen Turner’s Psychomotor Skills course is where many first-year students don surgical gowns and gloves for the first time. It’s also a training ground for handling syringes, performing venipunctures and tying sutures, albeit on cloth and foam models.

These early attempts at surgical skills often have unplanned outcomes.

“I blew the vein!” one student yells, laughing, as her first attempt to place an IV catheter makes her model limb leak blue-tinted liquid from its pipe insulation and neoprene sleeve.

Learning from mistakes and breaking a process down into steps are key lessons of the course, Turner and Lehman say.

“Practicing surgery skills — hand skills — seems to be the first time a lot of our students encounter something that’s really and truly a challenge to them, because you cannot succeed by studying out of a book or reading about it,” says Lehman, an assistant teaching professor who runs the CVM’s Simulation Lab. “You have to practice it, and you have to be willing to fail in order to get better.”

Student Eric Ortiz says he appreciates having this dedicated time to fine-tune his approach.

“I wanted to learn to use all the tools and get more stability in my hands,” he says. “Here, there’s more time for the instructors to focus more on your technique, or correct you, or just give you some one-on-one advice. The earlier we learn it, the more we can practice.”

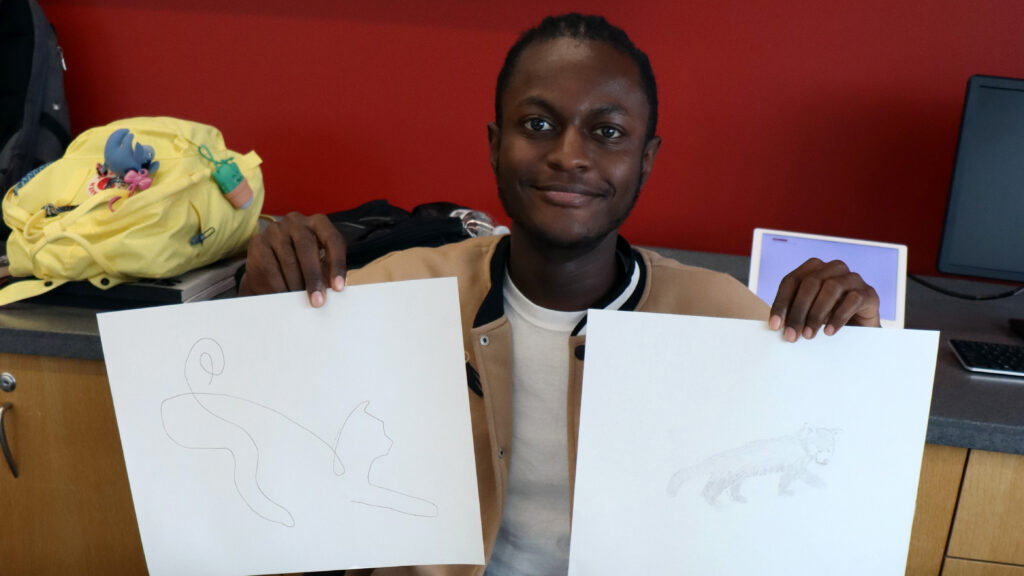

Elsewhere on campus, students in Dr. Michael Stoskopf’s Veterinary Illustration course evaluate each other’s drawings of various animals and insects. Several say this is their first time exploring an artsy hobby.

Stoskopf, a professor of wildlife and aquatic health, says veterinary students face increasing pressure to overwork themselves. It’s healthy for them to take the time to learn a slow, intentional craft that can help them de-stress.

“The class is really about life choices and realizing there’s more to life as a veterinarian than the bad cases, and we need to keep that balance,” he says.

Second-year student Xavier Crumel says the class was outside his comfort zone at first, because he had not drawn since childhood. He initially wanted to find a way to decompress after long days but is now inspired to keep sketching.

“Learning different techniques, such as stippling and shading, I really found that very therapeutic,” he says. “I’d give this experience a 10 out of 10, because I can actually see myself continuing drawing after leaving class because of how relaxing it can be.”