Saving the Life of an Uncommon Friend

She tells you exactly what her horse means to her without saying anything at all.

It’s in the way Regina Taggart lightly touches Yogi’s mane, how she pats his stomach and watches his reaction. It’s in her eyes, in glances of love and appreciation reflecting a bond that was unexpected but embraced.

Here, there is quiet contentment in Taggart’s light smile when Yogi tries to nibble on a shoe when plenty of grass is inches away.

It’s in the way they move together. Taggart guides Yogi as he grazes, and he moves slowly because Taggart does.

“I have a lot of support in my life, but he’s a special one,” said Taggart. “I have a great family. I have a great husband, but Yogi and I have a connection that’s beyond words.”

A year ago, it was difficult for Yogi to move at all. The 13-year-old starting having mild colic episodes that over time became more frequent and severe. While eating, he’d slowly lean downward in awkward displays of discomfort. He ate less and less and then barely at all. Taggart started seeing his ribs poke through.

It marked the beginning of a painful and challenging year, including four hospitalizations at the NC State Equine Veterinary Medical Center, where several treatment approaches seemed to immediately help, but just as quickly showed they really hadn’t.

But NC State’s equine veterinarians never gave up on Yogi and Taggart never gave up on them. That’s why Yogi is here today, and why Taggart still smiles.

Tackling a Medical Mystery

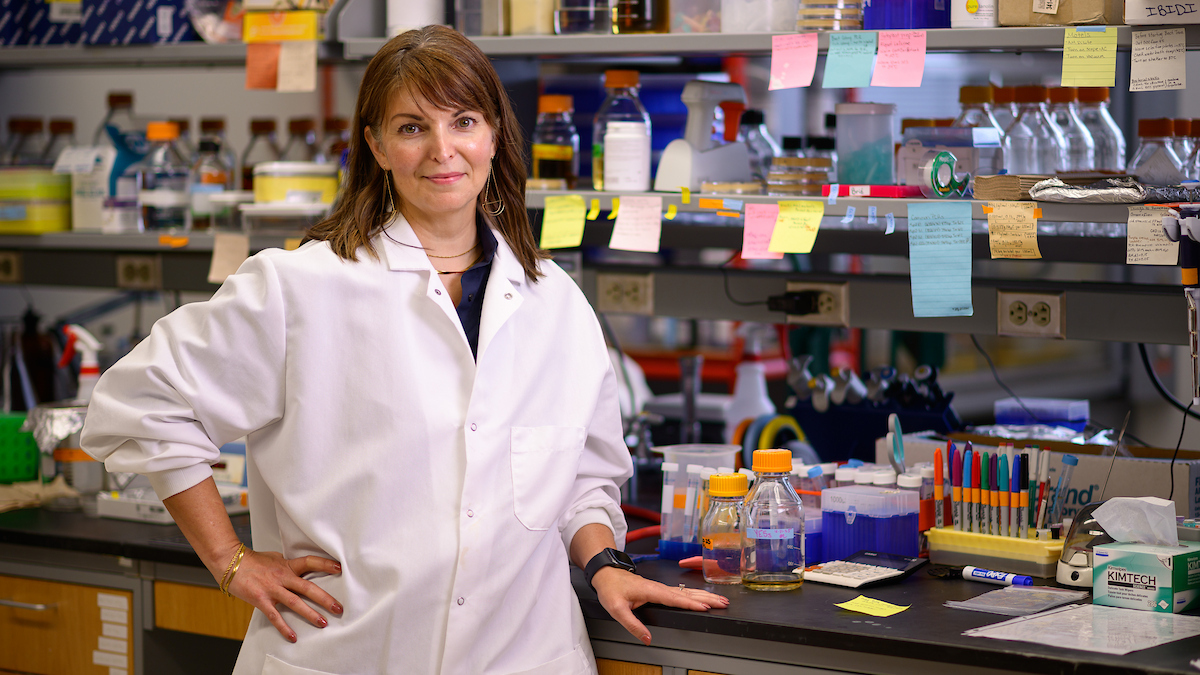

For Nimet Browne, it was like spending endless time trying to put together a big puzzle with pieces that never quite fit.

Yogi first arrived at NC State with mild colic, was seen multiple times by multiple doctors for recurrent colic and eventually diagnosed with severe gastric ulcers. Browne, clinical assistant professor of equine internal medicine, first saw Yogi last January during a recheck.

“He was doing quite well and then sort of started sliding back again,” said Browne. “His ulcers returned and he continued to have episodes of colic. It’s not really common for that to happen. So we delved deeper.”

“They said we can find nothing, we can find something scary or we can find something fixable,” said Taggart. “When it got to the point where I thought I could lose him, it was a hard decision and yet an easy one, because he had a chance. I knew we had to do something and they knew it, too.”

An ultrasound showed thickened tissue in Yogi’s small intestine, about double the size it should be. A biopsy led to a diagnosis of lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis, a common Inflammatory bowel disease. Yogi had a mild case, and he did well during monthly checkups.

Then, once again, Yogi started colicking every other day. Another ultrasound yielded another diagnosis — hemoabdomen. Yogi was bleeding internally and his doctors weren’t quite sure why. Hemoabdomen is uncommon for non-athlete or non-working horses like Yogi.

Browne and the equine team suspected trauma to his spleen, probably from being kicked by another horse or some sort of fall. During a weeklong hospital stay, the bleeding stopped and Yogi’s spleen looked good.

But he colicked again, and this time it was severe. The vets couldn’t get a handle on exactly what was going on inside Yogi, but they knew surgery was the only — and last — option.

“They said we can find nothing, we can find something scary or we can find something fixable,” said Taggart. “When it got to the point where I thought I could lose him, it was a hard decision and yet an easy one, because he had a chance. I knew we had to do something and they knew it, too.”

It was also a hard decision because of Taggart’s history with Yogi. A clinical social worker in private practice, she became curious about equine assistance as a form of therapy for clients. Taggart researched horse therapy and visited places that were successfully using it with children.

She found Yogi one day on a trip to Southern Pines, drawn to his sweet nature. At the same time, Taggart was struggling to cope with her own intensely stressful, emotional year.

“I had a really difficult year and a half and this guy was my rock,” she said. “Whatever I was feeling, he sensed it and was always there. When I felt confused or scared, Yogi stayed with me. I felt protected by him on each ride.”

After Yogi’s first visit to NC State, Taggart formed a bond with the equine staff, partly because Yogi saw almost every internist in the service and was also seen by the general medical and surgery services. Everyone from first-year residents to experienced surgeons saw Yogi and several formed close relationships with Taggart.

“It’s one of those situations that solidifies the importance of really listening to your client and understanding that they know their horse better than anyone else,” said Browne. “I think when she realized I believed her, that we believed there was something seriously wrong with Yogi even when he was presenting typically mild conditions, I think that’s when we bonded. She saw we were all working very hard to figure everything out.”

Taggart said it was her unbreakable trust in the team that gave her the strength to approve Yogi’s exploratory surgery.

“They deeply understand that this is an animal you love and you care about and they are going to do their best,” she said. “They made that clear and they connected with me. A lot of vets don’t do that.”

A Very Special Guy

The surgery lasted five hours. Staff, including internal medicine resident Erin Eaton, would periodically come out of surgery to tell Ragan that everything was going well, that Yogi was hanging in there.

“I remember Erin saying, ‘I’m determined to discharge him!’” said Taggart. “And then I realized what she meant was that he’s going to make it. He is not going to die.”

During Yogi’s procedure, clinical assistant professor of equine surgery, Timo Prange, found a narrowing at the very end of Yogi’s small intestine, right before it goes into the cecum, the beginning of the large intestine. Food was not able to probably move through the area, said Browne, so likely small bits of feed were getting stuck, leading to his severe abdominal stress.

For Yogi, Prange performed a rare bypass surgery and a complicated ileectomy, creating an opening between the cecum and ileum. A lesion found during the surgery likely explains the stomach ulcers and some of the small intestine inflammation.

“Everyone had a bit of a role in figuring out what was going on — everyone,” said Browne. “We don’t give up.”

Taggart waited around in the hospital until she could see Yogi; she wasn’t going anywhere. Yogi was shivering when he walked back into his stall and staff put a blanket on him; they told Taggart that was normal. At that point, it has been seven hours since his surgery began. For the next 48 hours, she visited her horse about three times a day.

Soon, the veterinarians let her feed Yogi by hand.

“It was only for five minutes, but it was amazing to see him just being a horse again. He was happy,” said Taggart.

Yogi stayed at the hospital for a while after surgery, often wearing a blanket with his name on it, though everyone knew who he was. Taggart would bring him organic fruit and carrots daily, which he shared with the horses around him, Browne said.

He gained weight and his personality returned. He would stick his nose out between the slats of his stall so Browne would give him treats. He would just stand there, looking at her until she did. If he didn’t get a treat, he would get visibly angry and shake his head.

“Among our horses, he didn’t spend the most amount of time in the hospital,” said Browne, “but he certainly had a very large impact on the people around him.”

Now, Yogi spends his time in a pasture overlooking a forest of high trees at Fox Valley Stables near New Hill, where he receives wonderful care and attention, said Taggart. After surgery, he didn’t colic for at least 30 days, the first time that had happened in more than a year.

Taggart usually visits Yogi twice a day — she spends most of her free time with him — and she often texts pictures of Yogi to some of his favorite clinicians at NC State. Recently, he was admitted to the hospital for a few weeks after suffering from an equine parvovirus that attacked his liver. The equine service saved his life again.

“I see him as a miracle,” she said. “He really is.”

Taggart is now able to spend time with Yogi on matters unrelated to his health. She’s working on his manners. The master of the art of begging is now learning how to stop when Taggart tells him to.

Taggart hopes to ride Yogi again one day again, though she said she’d be OK if that never happens. What she wants most is for Yogi to be his happy self and to be strong enough to gallop in the green, shaded pasture behind his stall.

“If I hadn’t found him, there would still be a big empty space, emotionally, in me,” said Taggart. “I don’t know what it would have been like without him.”

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine

- Categories: