Patient Spotlight: Puppy Thrives After New Hernia Surgery Approach

When newlyweds Ellen and Drew Williams were looking for a house in Raleigh, they knew they wanted a big backyard for a future puppy.

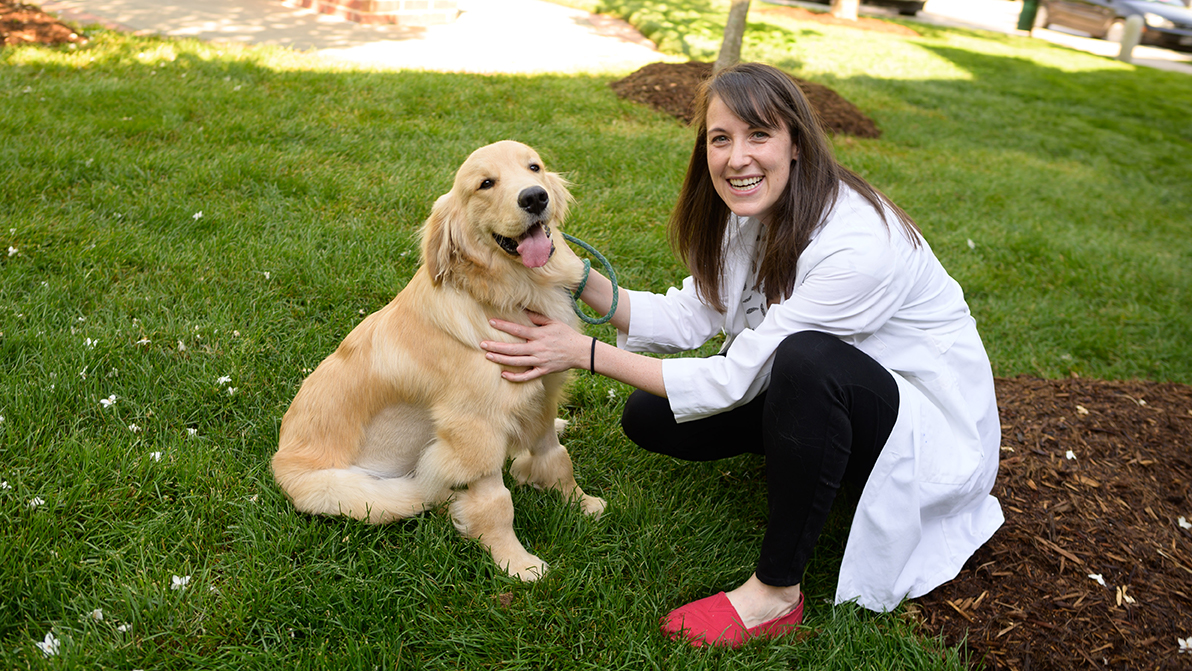

Not long after they were settled in, Drew surprised Ellen for her birthday with what she called the best gift ever. He told her they were on a waiting list to pick out a golden retriever puppy. The couple visited the breeder in Harrisburg, N.C., several times before they brought home 8-week-old Trout.

A few months later as the Williamses watched Trout play in their yard they noticed he had a runny, snotty nose instead of a healthy wet nose. To rule out pneumonia their veterinarian took radiographs of Trout’s chest, which revealed that some of his organs had herniated, or shifted, from their normal position to the space beside his heart through a hole in his diaphragm.

After a CT scan, Trout was diagnosed with a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia, or PPDH. His gallbladder and part of his liver had moved to his chest next to his heart. This type of hernia is rare in dogs, occurring only if a dog is born with an abnormal connection between the sac around the heart and the abdomen.

To learn more about PPDH and treatment options available, the Williamses did a fair amount of research on their own, including talking to human surgeons who were colleagues of Drew Williams’ dad, a heart surgeon in Greenville, N.C. The Williamses wanted to find a place that would perform Trout’s surgery laparoscopically and were referred to the NC State Veterinary Hospital’s soft tissue and oncologic surgery service. The minimally invasive PPDH repair would prevent a potentially life-threatening surgical emergency if his other organs herniated into the same space near his heart.

“As NC State alumni, we know that NC State’s Veterinary Hospital is one of the best in the country,” said Ellen Williams, who earned her bachelor’s in 2012; Drew Williams earned a degree in 2008. “We were overjoyed to learn how beneficial it would be to go the laparoscopic route. We are so thankful that NC State was willing to perform Trout’s surgery this way.”

A Different Approach

PPDH surgery in animals is not generally performed laparoscopically. Instead, the typical surgery involves a large incision in the abdomen and occasionally the chest to repair the diaphragm and move the organs into their correct location. This open surgery approach often means a longer recovery time and more potential for complications.

In laparoscopic surgery, surgeons make one or two incisions just large enough to insert the laparoscope, a wand-like instrument with a light and a camera that feeds video images onto a screen in the operating room. At the start of surgery, the abdominal cavity is filled with carbon dioxide gas, which is reabsorbed into the body after surgery, to give the surgeon a better view of the abdomen and more room to perform the surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery is commonly used for hernia repair in humans, including for treatment of PPDH. Valery Scharf, assistant professor of soft tissue and oncologic surgery, wanted to translate the technique to her veterinary patients, as laparoscopy has not yet been reported for use in animals with PPDH.

Trout’s surgery was not Scharf’s first laparoscopic hernia repair. She assisted with a similar repair of a different type of diaphragmatic hernia during her veterinary surgical residency.

“In veterinary and human surgery, we are continuing to develop new minimally invasive techniques for our patients, so we are constantly looking for ways that we can decrease the invasiveness of surgical treatments,” she said.

Scharf invited two surgeons, colleagues of Drew Williams’ dad, from East Carolina University to assist with Trout’s case: Mark Iannettoni, professor and chief of the division of thoracic and foregut surgery at the East Carolina Heart Institute, and Carlos Anciano, assistant professor of thoracic and foregut surgery and director of minimally invasive surgery at the Brody School of Medicine.

The two surgeons drove up from the coast for the procedure and brought suturing devices used in human surgeries to make Trout’s surgery more efficient. The two-hour surgery was successful and Trout went home the next day.

Scharf hopes to use this same technique for future patients and plans to continue collaborating with other surgeons to expand minimally invasive treatments.

“Minimally invasive surgery is becoming a viable approach to treating many diseases in human medicine, and by repairing these hernias laparoscopically in dogs, we are making those same standards a reality in veterinary medicine,” Scharf said.

Reducing Recovery Time

Recovery from minimally invasive PPDH surgery involves two weeks of kennel rest to give the tissues time to heal. For the Williamses, trying to keep a rambunctious puppy quiet was the hardest part of the process.

“Trout’s recovery is going great,” said Ellen Williams. “He has taken it better than we have. His cone and new haircut are the only ways anyone would know he even had surgery.”

Trout continues to follow his morning routine of carrying around his favorite stuffed dog and sleeping on his back with his giant puppy paws flapping in the air in his tiny puppy bed from when he first arrived at the Williams’ home.

“Every morning, my husband or I let Trout out of his kennel and he walks out, greets us with kisses and a wagging tail,” said Ellen Williams. “Trout then goes back into his kennel to grab his ‘baby,’ proudly taking it to his mom for cuddles. He carries that baby dog around every single day and sleeps with it every night.”

Soon he’ll be ready to play in the big backyard again with his second-favorite baby — a stuffed trout.

To learn more about the soft tissue and oncologic surgery service, visit their web page.

~Brittany Sweeney/NC State Veterinary Medicine

- Categories: