NC State Manufacturing and Veterinary Medicine Team up to Save Dog

At a time when the expectation is that we should all stay apart, the NC State Center for Additive Manufacturing and Logistics (CAMAL) has come together — safely, of course — with the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) and an industry partner to perform a miraculous procedure that saved the life of a dog and furthered medical research.

Several oncology departments within the CVM hold a weekly meeting to discuss cases that may require collaboration between them. At one of these meetings in June, Marine Traverson, CVM assistant professor of soft tissue and oncologic surgery, was introduced to a unique problem.

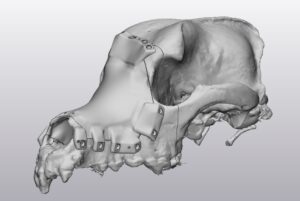

“That morning, one of our medical oncology residents, Dr. Susan Shapiro, presented the CT scan and the biopsy results of Sheba, a 10-year-old spayed female great Pyrenees that was affected by a very large tumor of her maxillary and nasal bones, the bones that form the snout,” Traverson says.

This particular tumor was relatively rare and remarkably invasive.

“Sheba’s was definitely one of the largest I had seen,” Traverson says. “The tumor had basically taken over the largest portion of her snout.”

Initially, surgery was not considered as a treatment option for Sheba because the tumor was so large that it looked inoperable. Suddenly, Traverson had a eureka moment. “I was looking at her CT scan in this virtual meeting and thought, she needs a 3D printed implant,” Traverson says.

Sheba’s owner liked the approach, so Traverson began building a team.

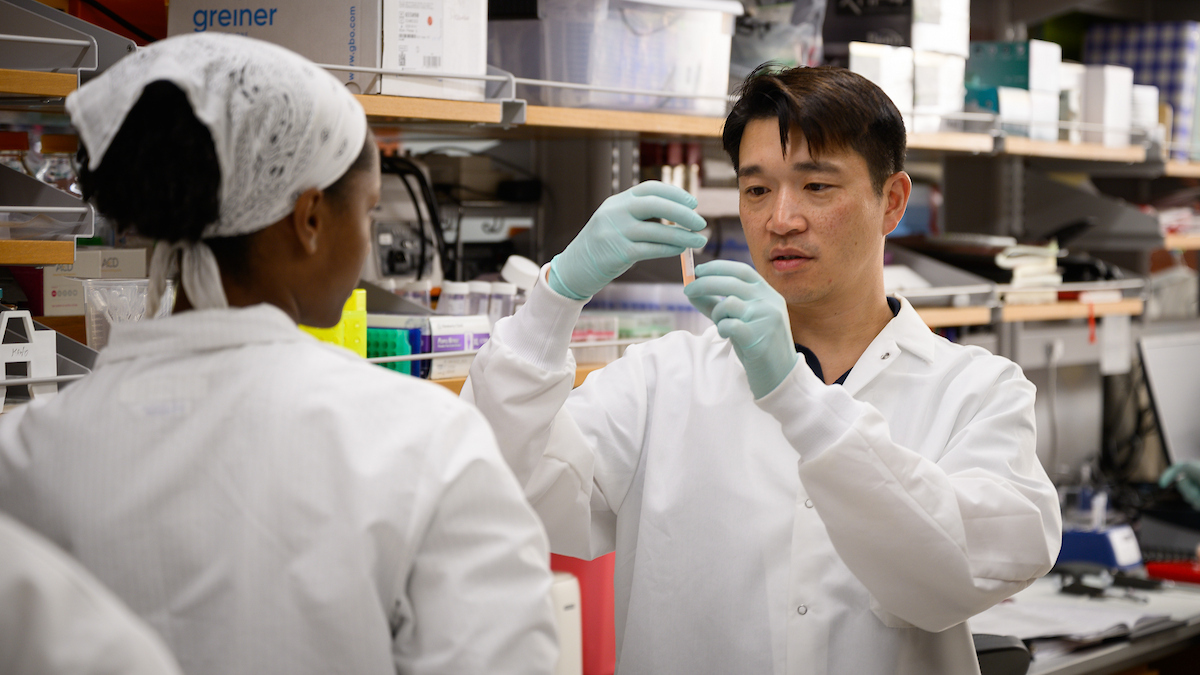

Getting the Team Together

Traverson first reached out to Ola Harrysson, director of CAMAL, at the end of June to get his opinion on the possibility of designing a 3D-printed, custom-made cutting guide. Harrysson and Traverson have a history of working on many projects in the past. “Dr. Marine Traverson contacted me shortly after joining the College of Veterinary Medicine in 2018. She had an interest in using 3D printing in oncology, and we started a collaboration right away,” Harrysson recalled. “We currently have a couple of funded projects, and we are working with six students from three different colleges.”

Harrysson jumped at the chance to work with Traverson on another project. “For this summer, we had several different student projects that were going to look at the custom design of implants and cutting guides for common oncology cases,” says Harrysson. “There are currently no good treatment options, and Dr. Traverson is interested in finding better solutions.”

With little time to plan, Harrysson recruited Maddie Wood, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, and Shelby Neal, a senior in chemical engineering. “I made sure to make it very clear that I wanted to be a part of the project as I saw this as an excellent learning opportunity,” says Wood.

“Marine shared the case with Ola, Shelby and myself in an initial meeting after she had reviewed Sheba’s CT scans,” says Neal. “She then formulated a general plan of removing the diseased bone with the aid of a cutting guide and reconstructing the anatomy using a patient-specific 3D-printed implant,” Wood says.

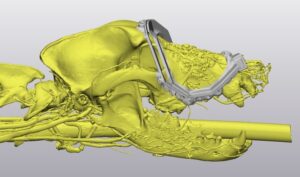

After this meeting, Wood and Neal received Sheba’s CT scans and began creating the design. “Our task was to design a cutting guide that could remove the tumorous bone, leaving enough margin around the tumor for error, and then design an implant to replace the removed bone,” Neal says.

The team’s final member, Jeremy Knight, a medical application engineer at Materialise, joined the project when Traverson reached out for additional help to create the surgical guide and prosthetic implant. He provided the technical assistance with Materialise’s anatomical modeling software, the Mimics Innovation Suite.

“The goal of this project was to create and 3D-print a surgical cutting guide which would assist Dr. Traverson in completing a maxillectomy procedure,” Knight says. “This surgical procedure requires extreme precision due to the delicate nerves and soft tissue within close proximity, which is why it’s necessary to use a guide.”

To create the prosthetic implant to replace the removed mass, they isolated the tumorous region using Materialise’s 3-Matic software. Then they modified it to look like the form and structure of a healthy dog. Materialise has a been in support of medical applications of 3-D printing at NC State since 2003, says Knight. With Knight’s expertise and Materialise’s support, they could design the items Sheba needed for surgery.

When it came time to print the parts, Matt White, an integrated manufacturing systems engineering student, stepped in when the team needed consulting on manufacturing capabilities. White was off-campus at an internship where he worked with additive manufacturing processes.

“We were operating EOS [medical imaging] machines and printing a material that happens to be a biocompatible polymer,” he says. “CAMAL is not currently outfitted to produce biocompatible polymer components, and due to my connection from working in the lab, I was able to fabricate the components.”

He quickly made the parts and had them ready the next day.

The Surgery

Creating the surgical guide and implant had its difficulties. Various clinical and engineering factors required multiple revisions to the design.

“These projects that involve real patients are always very time consuming and stressful since you usually don’t have a lot of time, and you have to get it right the first time,” Harrysson says. In this case, the implant and cutting guide’s original design took about three weeks, and the tumor grew too much during that time for the implant to fit Sheba accurately.

“As a result, we had to redo the entire project in three days to get it ready for surgery,” says Harrysson.

With their team’s support and skill, they were able to manufacture the parts just in time.

“A project like this can’t be done without the multidisciplinary team,” Harrysson says. “The fact that so many people came together with a wide variety of skills truly made this project a success.”

It required the surgeon to decide how much tissue to remove and where the implant can be attached using screws. The engineers are needed to design and fabricate the models, implants and cutting guides.

“We have been working with the vet school for almost 20 years on various cases, and none of them could have been done without the multidisciplinary team,” said Harrysson.

The team ensured that Sheeba’s surgery was a success, and two days later, she returned home to recover.

“I have been in touch daily with her owner since, and day after day, Sheba has recovered her stubborn, charming personality,” says Traverson.

Future Applications

The use of 3D printing technology is relatively new in veterinary surgery, especially in oncologic surgery, and it is just starting to show its full potential.

“3D printing is primarily used for very complicated cases where regular treatments or implants are not available,” Harrysson says. “By doing these complicated cases, we push the limits of what is possible and will offer better treatments and solutions for both animals and humans.”

Traverson agreed.

“I highly believe that it has a role to play and can optimize the surgical accuracy and the reconstruction of the anatomy after large tumor removal,” she says.

For what it’s worth, Sheba doesn’t seem to care that she was part of pushing a revolution in medicine even further. She is just happy to be home resting comfortably with her loving family. Good girl.

Story provided by the NC State Center for Manufacturing Additives and Logistics.