Groundbreaking Transplant at NC State Helps Jumping Horse Stay the Course

Aided by cutting-edge growth factor research and state-of-the-art ultrasound technology, NC State ophthalmologists successfully performed one of the largest equine corneal transplants ever reported.

In a medical breakthrough, NC State ophthalmologists have successfully completed one of the largest resections and corneal transplants ever reported in a horse, replacing about 60% of the show-jumping animal’s right cornea and then using a novel technique of introducing platelet-rich fibrin, or PRF, proteins onto her eye to encourage healing.

Dutch warmblood horse Myra, which Dr. Michelle Carnes and her husband bought in the Netherlands last fall, somehow injured her cornea while moving to the United States and introduced a fungus that would nearly cost her the eye. As Myra’s infection worsened, Carnes, a veterinary neurologist and neurosurgeon, consulted ophthalmologists across the East Coast and realized the NC State Veterinary Hospital was Myra’s best chance at recovery.

“If anybody was going to be able to save Myra’s eye, it was the NC State team,” she says.

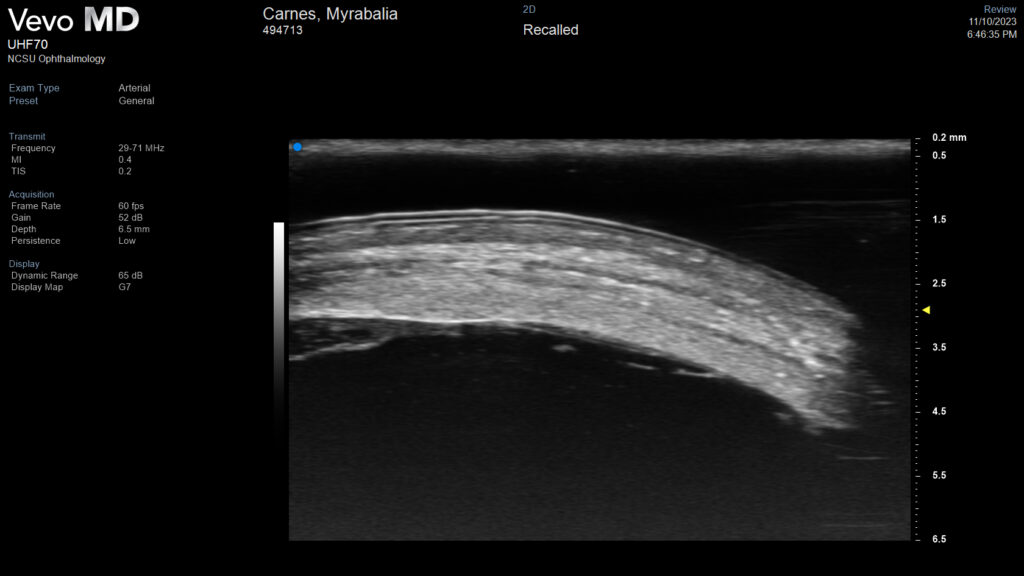

Before Myra arrived at NC State in November, she was diagnosed with a treatment-resistant stromal abscess. As NC State veterinarians cared for the 6-year-old mare over nearly three months, they depended on advancements unique to the College of Veterinary Medicine, from the research exploring PRF use in veterinary ocular surgery to the ultra-high-frequency ultrasound ophthalmologists used to see her infection’s spread, to save the athlete’s vision.

A Complex Injury

Carnes and her husband fell in love with Myra’s sweet demeanor and sharp intelligence while searching for a Dutch show-jumping horse last year. They quickly purchased her and flew her into New York City’s John F. Kennedy International Airport on Sept. 22.

Myra spent over two weeks in two separate required quarantines, during which veterinarians noticed she was not opening her eye and initially treated her for blunt trauma, Carnes says. As soon as Myra’s quarantine ended, Carnes had her seen at the University of Georgia’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital, which is closer to her farm in Tryon, North Carolina.

UGA veterinarians diagnosed her with a stromal abscess caused by a fungal infection deep within her cornea.

“That, as a horse owner, is a devastating diagnosis, because you know that condition can go south really, really fast,” Carnes says.

Myra responded to antifungal treatment at first, but a recheck showed the infection spreading. Georgia ophthalmologists said Myra would likely lose the eye, Carnes says.

A small animal ophthalmologist friend in Florida recommended that Carnes contact Dr. Brian Gilger, an NC State professor of ophthalmology and leading expert in equine ocular diseases.

Gilger and Dr. Michala Henriksen, an associate professor of ophthalmology with expertise in equine ocular fungal infections, promptly replied they would take Myra’s case.

Myra arrived well after hours at NC State on Nov. 10, and the waiting ophthalmology team immediately started her treatment with an examination, a new ophthalmic catheter and an antifungal injection.

They then used an uncommon, specialized gadget called an ultra-high-frequency ultrasound to get a better look at the eye. NC State is one of few universities nationwide that have this advanced device, which lets ophthalmologists see deeper into the eye in more detail than traditional scans allow.

“This ultra-high-frequency ultrasound really transforms how we’re managing these horses’ eyes, because we can see so much better where the disease really is,” Gilger says. “It allows us to see through tissues that are white or opaque and examine underlying structures, something we cannot do with the usual ophthalmic instruments.”

The ultrasound showed surgical intervention was possible to save Myra’s eye, but the odds were daunting.

“Generally, if abscesses are greater than a centimeter in diameter, we know that there’s a very low chance of actually saving the eye, even after surgery,” Gilger says. “Myra’s measured about 1.4 to 1.6 centimeters.”

The team decided to first try antifungal and anti-inflammatory treatment, including luliconazole, a medication whose use in horses Gilger researches. That regimen worked at first, and Myra was discharged to the Tryon farm for a week in late November.

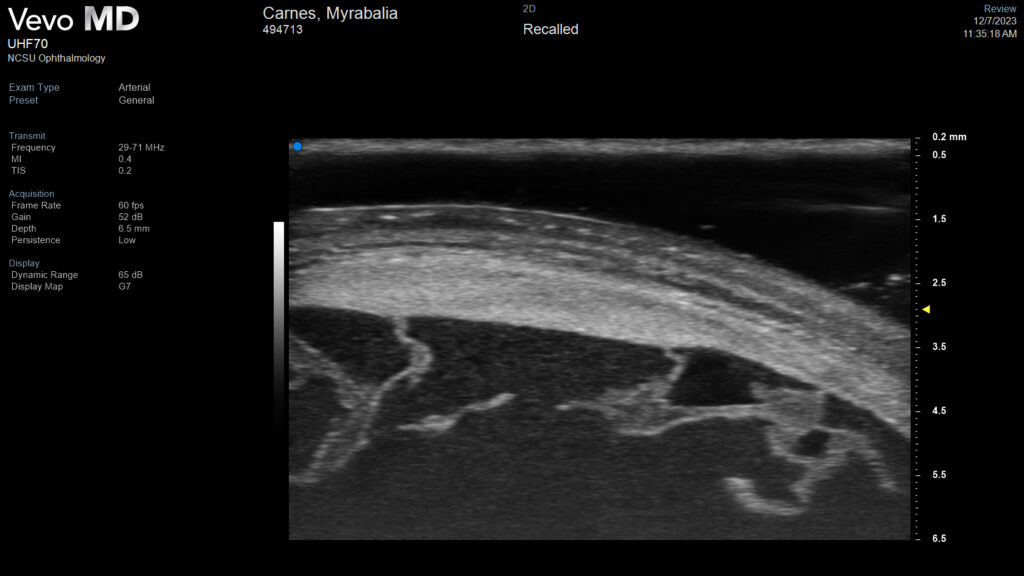

When recheck imaging later showed Myra’s abscess was resisting treatment and breaking into the anterior chamber of her eye, the team had to take the leap. Myra had a surgical resection and corneal transplant Dec. 8.

Ophthalmologists removed 60% of Myra’s cornea to excise the infected tissue and sutured in cryopreserved cornea from a deceased horse whose owner consented to donation. The donor cornea served as a scaffold for Myra’s eye to grow new tissue into the area, Gilger says.

They placed a conjunctival graft over the corneal graft to protect her eye from infection and encourage tissue regeneration and healing.

But their challenges weren’t over. Myra’s conjunctival graft unexpectedly detached within two weeks, revealing that her cornea had ulcerated underneath. The ulcer showed few signs of regrowing its protective epithelial layer on its own, and ophthalmologists decided to introduce growth factors to kick-start the tissue repair.

Platelet-rich fibrin is derived from the same proteins in the blood that produce clotting. It is increasingly being used in human medicine and dentistry for its regenerative properties, because it stimulates the formation of new connective tissues within surgical sites or injuries.

Henriksen has studied the clinical use of PRF in dogs with corneal ulcerations and found it helped their injuries heal quickly. She’s launching another clinical study evaluating its use in horses like Myra.

“It’s basically tissue glue with healing power,” Henriksen says. “And in Myra’s case, it led to a drastic improvement in her vascularization, or how her blood vessels were growing into the graft, and boosted her scar tissue healing.”

Similar to how PRF research entered the veterinary world from human medicine, NC State ophthalmologists are conducting research into wound healing and fungal disease treatment in horses and small animals that can one day translate to human therapies.

For example, stromal abscesses caused by fungal infections are commonly diagnosed in humans living in hot, humid climates. Rising global temperatures are causing outbreaks in previously unaffected areas, and NC State ophthalmologists’ research into treatments like luliconazole for veterinary eye infections could promise results in human ophthalmology.

“Myra’s case really goes to show why we all work in an academic institution where you have access to novel and innovative procedures,” says Erin Barr, a registered clinical technician in ophthalmology and a Veterinary Hospital employee since 2006. “I’m just grateful to be a part of it.”

Seeing how these state-of-the-art treatments benefited Myra showed early-career veterinarian Nicole Himebaugh, a third-year ophthalmology resident, new ways to approach stubborn conditions.

“Making those day-to-day decisions, changing Myra’s treatment protocol depending on her needs and seeing how it was helping her added to my clinical background, which is always helpful,” Himebaugh says. “It was nice to see the progression, the treatment and the outcome.”

Myra’s case was even a learning opportunity for seasoned veterinarians, including her owner.

“There were definite periods of time where I saw things truly from a client perspective, because some of the stuff that they were doing is just foreign to me,” Carnes says. “Who knew you could actually remove 60% of the cornea in surgery, replace it with a donor cornea, and the eye will still work? I didn’t know any of that, and I’m a specialist.”

Going forward, Myra is expected to retain much of her central vision in her right eye but will not recover her hind vision, “like she has built-in blinkers,” Henriksen says. The scar tissue on her cornea may appear opaque, but Myra will be able to exercise and compete in jumping events just fine.

“As a person who is in the veterinary profession, I know how difficult it can be sometimes and you get busy,” says Carnes, who practices in Florida. “But everybody on the ophthalmology service, the doctors, residents, students and the technicians, they were all absolutely lovely. And Myra keeping her eye is a testament not only to the expertise of the team, but the unmatched compassion and love they showed her.”

Looking Ahead

Myra’s friendly attitude not only helped her tolerate extensive treatments but also charmed everyone who worked on her case. She would greet the ophthalmology team with neighs as they approached her stall and nudge their pockets searching for peppermints when they prepared her for grooming or walks.

Most patients are hospitalized for 7 to 10 days at the longest, Barr says. Myra’s 73-day stay, coupled with her cheeriness, led caregivers to form a close bond with her.

“When a horse reaches out to your heart like that, it’s really hard not to get attached,” Barr says. “Everybody’s invested, from the treatment technicians to the overnight staff and the people who cleaned her stall. From the ophthalmology team to the whole equine hospital team, it really was just an incredible group effort.”

Myra was cleared to go home at the end of January. The ophthalmology team threw her a small going-away party during her last week, complete with a carrot cake, and sent photos to Carnes.

“They continually went above and beyond with Myra’s care and their communication with me,” Carnes says. “All of their updates made it easier to be away from her. At that point, NC State knew her better than I did.”

Carnes clipped Myra’s coat for Florida weather once she arrived home and was impressed that she had retained her muscle mass, in spite of her lengthy stall stay and enthusiastic treat-eating.

Myra’s healthy condition is a testament to NC State’s comprehensive care, Carnes says.

“It’s just amazing,” she says. “She’s doing great on a fitness plan to give her time to build up her strength. Myra loves having so much more space now and has outbursts where she bucks out of joy.”

And Carnes already has a VIP guest seat saved for Myra’s return to the arena.

“Dr. Henriksen said she’s going to come to Tryon and watch Myra in a horse show,” she says. “I’m going to hold her to that.”