Interpersonal Expertise: NC State a Veterinary Leader in Cultivating Student Communication Skills

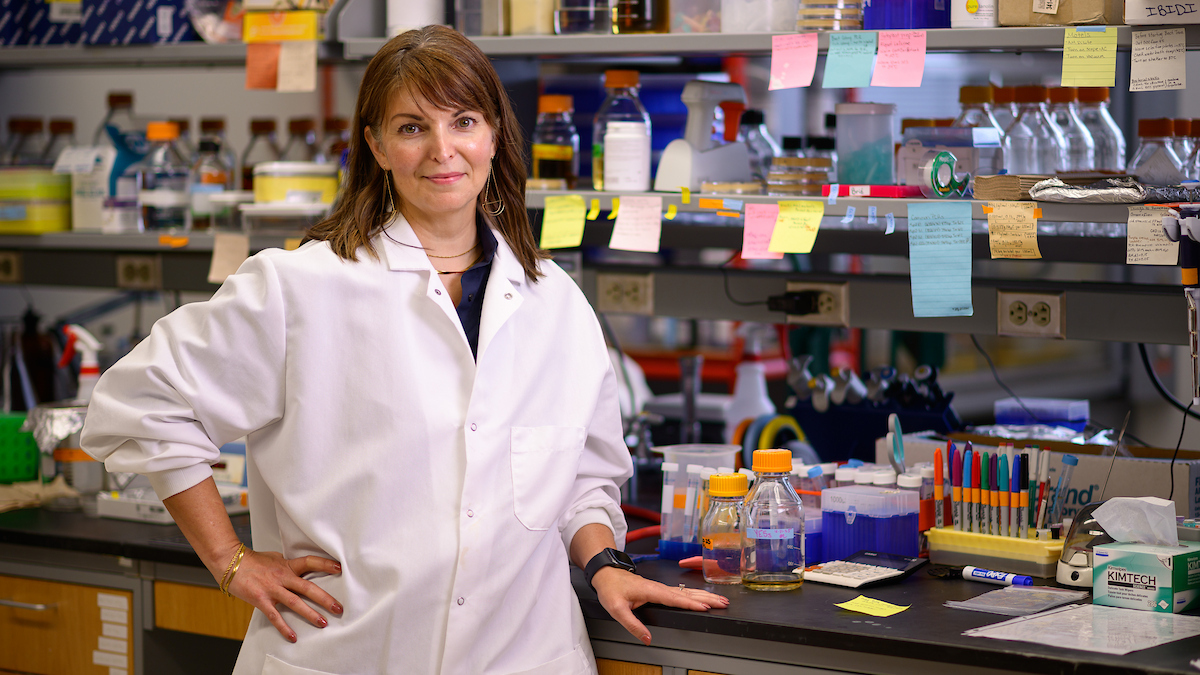

Dr. April Kedrowicz, who holds a Ph.D. in communication, does even more than institute new ways to teach critical skills to NC State College of Veterinary Medicine students. She also researches their efficacy and explores communication-related issues important to the veterinary profession.

At NC State, having veterinary students master critical communications skills is on par with having them conquer cranial anatomy, and the job of leading the lessons in language belongs to Dr. April Kedrowicz, an associate professor in the college’s Department of Clinical Sciences.

Kedrowicz, who holds a Ph.D. in communication, is an expert in training others how to cultivate verbal and nonverbal skills. She has incorporated communication instruction into every unit of the Becoming a Professional thread she leads as part of the new five-thread curriculum that the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine adopted last year.

Alongside learning to identify muscle groups, diagnose equine colic and complete intricate surgeries, veterinary students practice listening to clients in distress, communicating difficult medical concepts and becoming better team members with their colleagues.

“They’re learning the importance of communication with clients and making those connections between what they say, how they behave, how they listen,” Kedrowicz says. “They know that is going to impact what clients do when they leave the clinic. I want them to communicate with clients in a competent manner, but ultimately the reason that is so incredibly important is because it impacts animal health.”

NC State has led the way in incorporating the American Association of Veterinary Medical College’s move to Competency Based Veterinary Education in its new curriculum, whose other threads for students starting with the Class of 2028 are Animal Health and Disease, Exams and Interventions, Form and Function and Integrated Applications.

Dr. Jan Hawkins, head of the NC State Department of Clinical Sciences, says Kedrowicz is truly unique in the field of veterinary education, offering structured laboratory experiences for students on difficult situations such as advising clients on euthanasia for their pets or resolving interpersonal conflicts. In July, she’ll become the only full professor in the department who doesn’t hold a doctor of veterinary medicine degree.

“I am not familiar with anybody at any veterinary school who’s not a DVM who is involved in health care communication, and she is outstanding,” Hawkins says. “I think that says a lot for her, that she took something like veterinary medicine that wasn’t her background but immersed herself in it. And it says something about the foresight of NC State to recognize that having an expert teach communication skills is important. We’re just really fortunate to have her here.”

Backed Up with Facts

What also makes Kedrowicz unique is that she has the data to back up her teaching prowess. Over the past decade, Kedrowicz, a national Competency Based Veterinary Education leader and member of the AAVMC’s Council on Outcomes-based Veterinary Education, has published more than 30 studies on the efficacy of communication education strategies and on communication-related issues important to the veterinary profession.

Her two most recently published papers fall under the latter category. One looked at the importance of competent communication in enhancing whether clients adhered to antimicrobial recommendations, and the other explored the hidden curriculum in communicating dog breed stereotypes during veterinary clinical training. Results of both research projects were published in the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education.

“What those two studies have in common is they both highlight the hidden curriculum that our students get exposed to, one with respect to antibiotics and having those conversations, and one with respect to how we identify and manage pain in dogs,” she says. “The hidden curriculum is anything that students take in that is not a part of the formal curriculum or a purposeful educational initiative — things that they see role models do.”

The studies found that students very much internalize what they see clinicians doing, which affects their perceptions on how well clients will adhere to antibiotic instructions or on how to identify pain in particular dog breeds.

Sometimes they see things that enhance what they’ve learned in their preclinical coursework and things that might be at odds with what they learned, she says.

“That came out with the dog breed stereotypes,” Kedrowicz says. “Students are taught there’s no difference in pain threshold based on breed of dog, but when they get to clinics, the messages might be a little different. Maybe we rely on shortcuts based on prior experience with specific breeds. Maybe we are doing some pain scoring in our head as a clinician, but we’re not verbalizing our thinking so our students think we’ve made a leap based on the dog that’s in front of us.”

The study — led by post-doctoral graduate Rachel Caddiel and co-authored by Dr. Margaret Gruen, professor of behavioral medicine, and Dr. Duncan Lascelles, professor of small animal surgery and pain management, all of NC State — was based on observations during a clinical rotation block across three specialties.

Best in the Country

For the antibiotics adherence study, co-authored by Dr. Erin Frey, assistant teaching professor at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, and research specialist Mari-Wells Hedgpeth, the team conducted 11 focus groups with 33 veterinary students across all years of the curriculum. Analysis of the transcripts revealed five main themes: the importance of client education and health literacy, navigating client expectations, barriers and enablers to client adherence, navigating generational differences among colleagues and clients, and the impact of role modeling in the clinical setting.

The study’s results should lead to the next generation of veterinary students being able to confidently communicate about antibiotics, enhance client adherence and increase the likelihood of positive patient outcomes.

“We’re getting a sense of our students’ understanding of client adherence and client perceptions and how their own communication is going to impact adherence and ultimately patient care,” Kedrowicz says. “So that’s bigger than just, ‘Here’s the training.’ It’s really about getting them to acknowledge that their ability to communicate well with clients is going to have a direct impact on patient care.”

Kedrowicz, part of an AAVMC leadership team that is instrumental in training other schools in Competency-Based Veterinary Education, also teaches a graduate seminar on team science and communication to Ph.D. students in NC State’s Comparative Biomedical Sciences program.

“Our communication program is the best in the country because of the breadth and depth our students get exposed to regarding interpersonal interactions, teamwork and professionalism every semester for six semesters,” she says. “They are very well-prepared to enter that clinical year, and once they’ve completed that clinical year, they’re very well-prepared to go out and be veterinarians.”

Kedrowicz also mentors her colleagues, and Hawkins says he happily has been “an old dog learning new tricks.”

“She’s very astute, so she picks up on things we should be working on or things that we could improve,” he says. “For the students, the impact she has is indispensable to their education. Half of what we do on a daily basis revolves around effective communication. Her work helps them in their day to day practice, yes, but more importantly it helps them in life.”