From the Wilds of Kentucky, Chase Carey Reports

Students at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine have access to all kinds of internships, externships and research experiences during their four years of school. This summer, several students are sharing some of what they're doing and learning in real time.

Since my last dispatch, my internship has slowed down considerably, which has its benefits and drawbacks. I have not been out in the field as much, which has been a plus considering the 90-degree heat we have been experiencing! Most of my days have been spent in the lab performing necropsies (including a black bear and a great blue heron) and organizing hundreds of Chronic Wasting Disease samples from the past four years.

CWD is an emerging threat to wildlife across Kentucky, which just had its first known positive case this past winter, and across the Southeastern United States. Monitoring the disease requires an intense, statewide effort each fall and winter that results in the KY Wildlife Health Program having to manage the collection and testing of thousands of lymph nodes from harvested deer. All of the ones in our lab have already been tested, but the WHP has to maintain the database of collected samples for future research and monitoring purposes. As a result, I have been working with the other technician to sort all of the samples from each county of the state from 2020 to 2022, which has taken up a lot of our time!

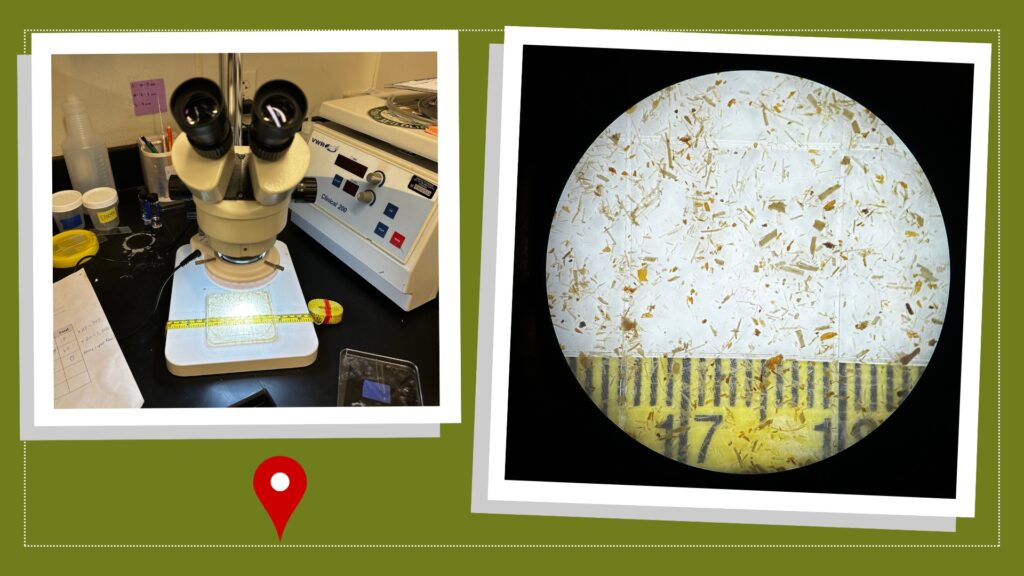

Another project I have been working on has been our elk abomasal parasite counts. APCs are a valuable wildlife management tool that allow biologists to estimate where a population of deer is relative to the carrying capacity of their environment — as in, whether they are over or underpopulated. This is measured by collecting the abomasum (one of the four chambers of a ruminant stomach, like cows and deer have) and washing it through a very fine filter that collects only the stomach contents. We then dilute these stomach contents with ethanol and carefully examine them under a dissecting microscope for the presence of parasitic worms. Most of these worms are less than 8 mm long and hardly visible to the naked eye! We remove each worm, determine its sex for research purposes and then add up the total for each elk. Then we used a research-based formula that provides an estimate of the state of the population. It is a very neat process that I had not heard of before coming to Kentucky.

As my internship comes to an end, I have begun preparing a presentation for the KY One Health Awareness group, which consists of public health officials, veterinarians and agriculture officials from across the state. I will be giving a talk on the tick surveillance project that I have helped with this summer, as well as the growing One Health threat of tick-borne diseases in humans, livestock and wildlife. One Health is a growing movement in the medical profession and beyond that seeks to examine and understand the relationship among human health, animal health and the environment. If you need an example as to why this is important, maybe you’ve heard of COVID-19?

I also wrote a case briefing for the KDFWR WHP newsletter about a recent diagnosis of an American mink in Kentucky with highly pathogenic avian influenza (“bird flu”), which you might have been seeing a lot in the news recently as dairy cows and workers have become infected. Emerging diseases and how they spread between humans and animals is of growing interest to me as it will likely be a large part of my future career as a wildlife veterinarian.

I am grateful for all that I have learned this summer and the ability to see how my veterinary education can be combined with a passion for wildlife health and conservation. It has been a pleasure to share part of my journey with you all from the field. I hope you’ve learned a thing or two, but — if nothing else — remember to check yourself for ticks!

June 25, 2024

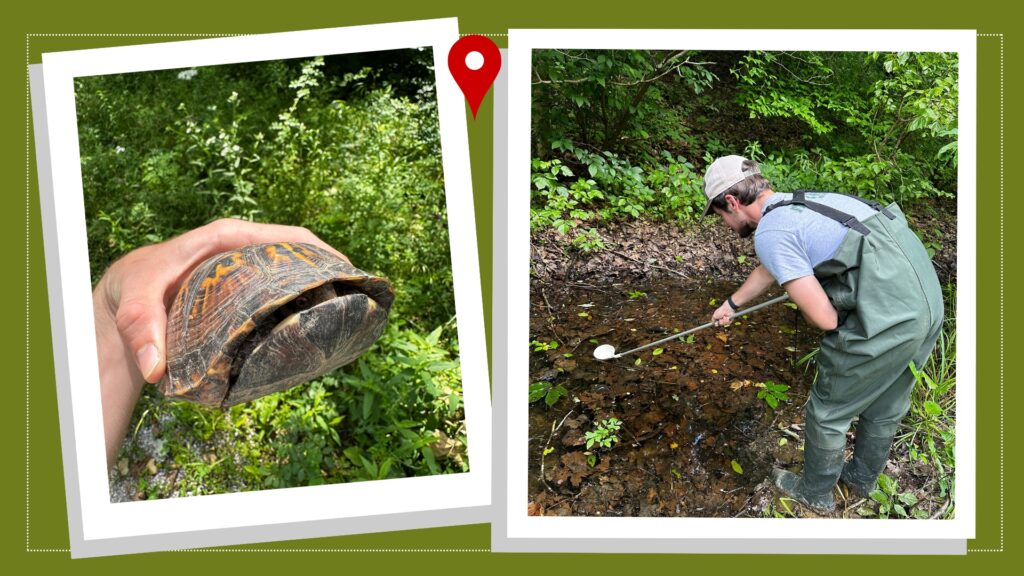

After my last dispatch, I spent dozens of hours in the field (literally) working mostly on our tick surveillance project, but also on our amphibian disease surveillance project.

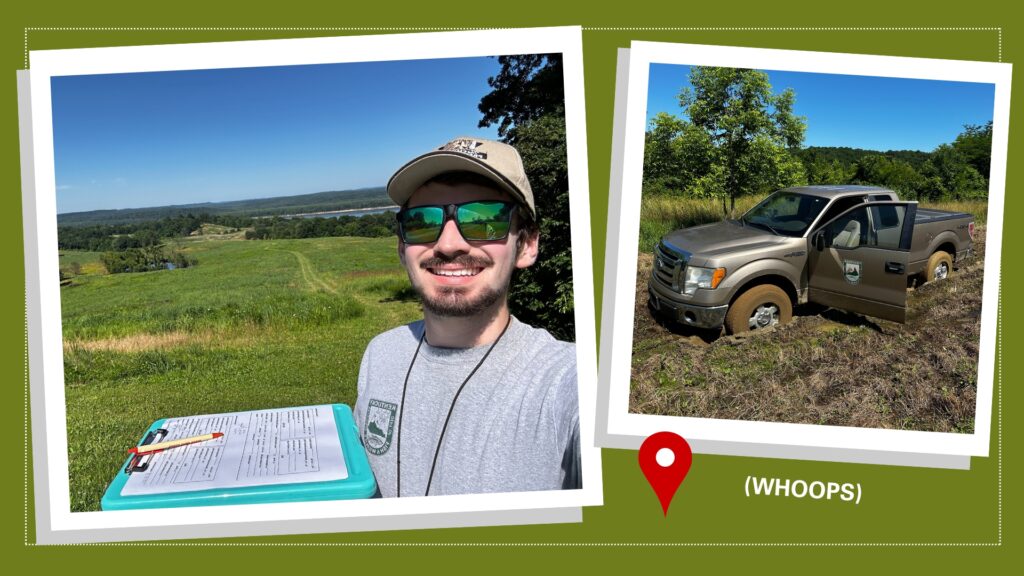

There were many 12+ hour days spent in the hot Kentucky sun fighting off a constant swarm of ticks, mosquitoes and cicadas. One day, I unfortunately got the field truck stuck in a muddy field and had to wait for a tractor to come along and pull me out!

Another day, after a strong weekend storm, we came across a fallen tree on a back road leading to a couple of our sample sites. Armed with nothing but a dull machete/hand saw tool, I became drenched with sweat as I attempted to saw through a smaller limb that was sticking above the rest. Eventually, my coworker and I were able to break it off and slide the tree sideways just enough for us to get the truck over. Though it probably would have taken less time to walk to our sites, I’d like to count it as a win!

Last week, we were visiting our last sample sites for the season, which included one particularly buggy pond. The mosquitoes were so large and aggressive that I could feel each one as it landed on my exposed arms and neck. Covered in spider webs, sweat and blood-sucking fiends, I had for once just begun to pine for the cool A/C and sterile environment of the anatomy lab when I heard a rustle in the leaves. To my right, I saw a young buck approaching the pond we were sampling. He seemed undisturbed by our chitchat as he continued exploring the leaves and ambling toward us. He got to within about 20 yards of me before we made eye contact and he darted off into the woods. It was then that I realized why I do what I do. Despite the rugged conditions, there’s nothing like working in the great outdoors!

Since the conclusion of our field work, most of my time has been spent in the lab, organizing our samples and performing necropsies. Most of these have been on muskrats as part of a research project on muskrat population health, but I have also done a few wild turkeys and red foxes, looking for different diseases and parasites (pictures not included, for obvious reasons!).

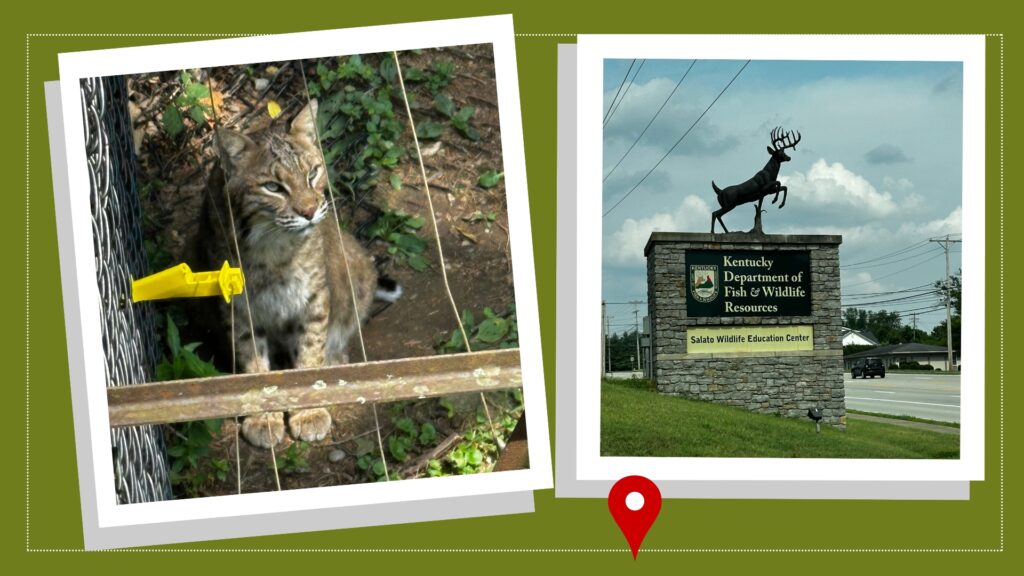

Most recently, I assisted the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources with its annual goose banding at the Department HQ. We rounded up about 20 to 25 Canada geese to be banded for population-level research. I was able to get my hand on a few to assist with banding, which was conducted with proper federal permitting. They were a bit feisty, but I’d much rather handle them than a fractious cat! No geese were harmed in any way during the process, and they all were safely released back into a pond. This work wasn’t directly related to my internship, but it was another great opportunity to get out of the office and get my hands dirty.

JUNE 4, 2024

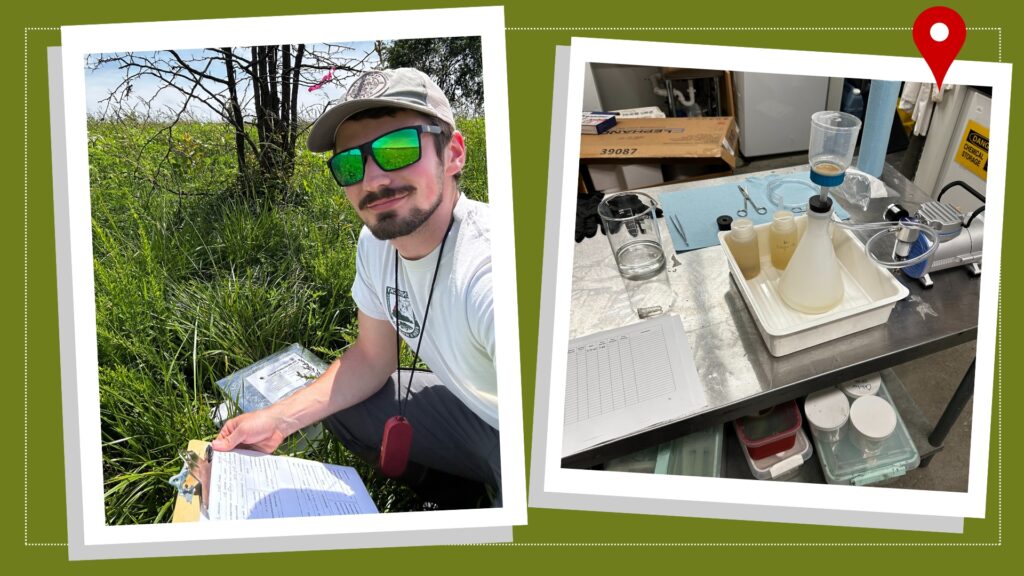

I’ve been working in Kentucky only about two weeks now, but it has been packed full of new and interesting experiences.

This summer, I am working as a wildlife health intern for the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, under one of only a few dozen state wildlife veterinarians in the United States. I have been able to jump in on a number of research projects exploring emerging diseases of wildlife in the state.

The majority of my time has been spent on our tick surveillance and eDNA monitoring projects, which have been very interesting and challenging. For our tick surveys, we put out CO2 traps that use dry ice to attract ticks and catch them on sticky tape. Additionally, we drag a large cloth on the ground vegetation across a transect to catch ticks sitting on the plants. The ticks are then collected in vials and sent to a wildlife lab in Georgia for identification and disease testing. We are looking to see which species of ticks and the diseases they carry are present in Kentucky across different habitats (such as forests or open fields). Needless to say, I have found too many ticks on me to count!

Our second project involves collecting water samples from ponds across the state and testing them for eDNA, or environmental DNA, of specific amphibian diseases. The project is part of an ongoing effort of the KDFWR Wildlife Health Program to monitor emerging amphibian diseases, such as Chytrid fungus (Bsal) and Ranavirus. We collect the water in small bottles and then filter them through a small paper filter that is able to collect the eDNA for testing. This process is super exciting to learn about and see in action!

I also have been able to perform a few necropsies on wildlife and deer to examine the cause of death and collect organ samples for disease testing and research purposes. While all of this may not seem like glamorous work, I see real purpose and excitement in it. I have loved seeing how the disease processes and veterinary concepts we have been learning at the CVM are being applied to real-world conservation issues!

- Categories: