From the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, Emma Eldridge Wraps Up

Students at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine have access to all kinds of internships, externships and research experiences during their four years of school. This summer, several students will be sharing some of what they're doing and learning in real time.

FRIDAY, AUG. 4, 2023

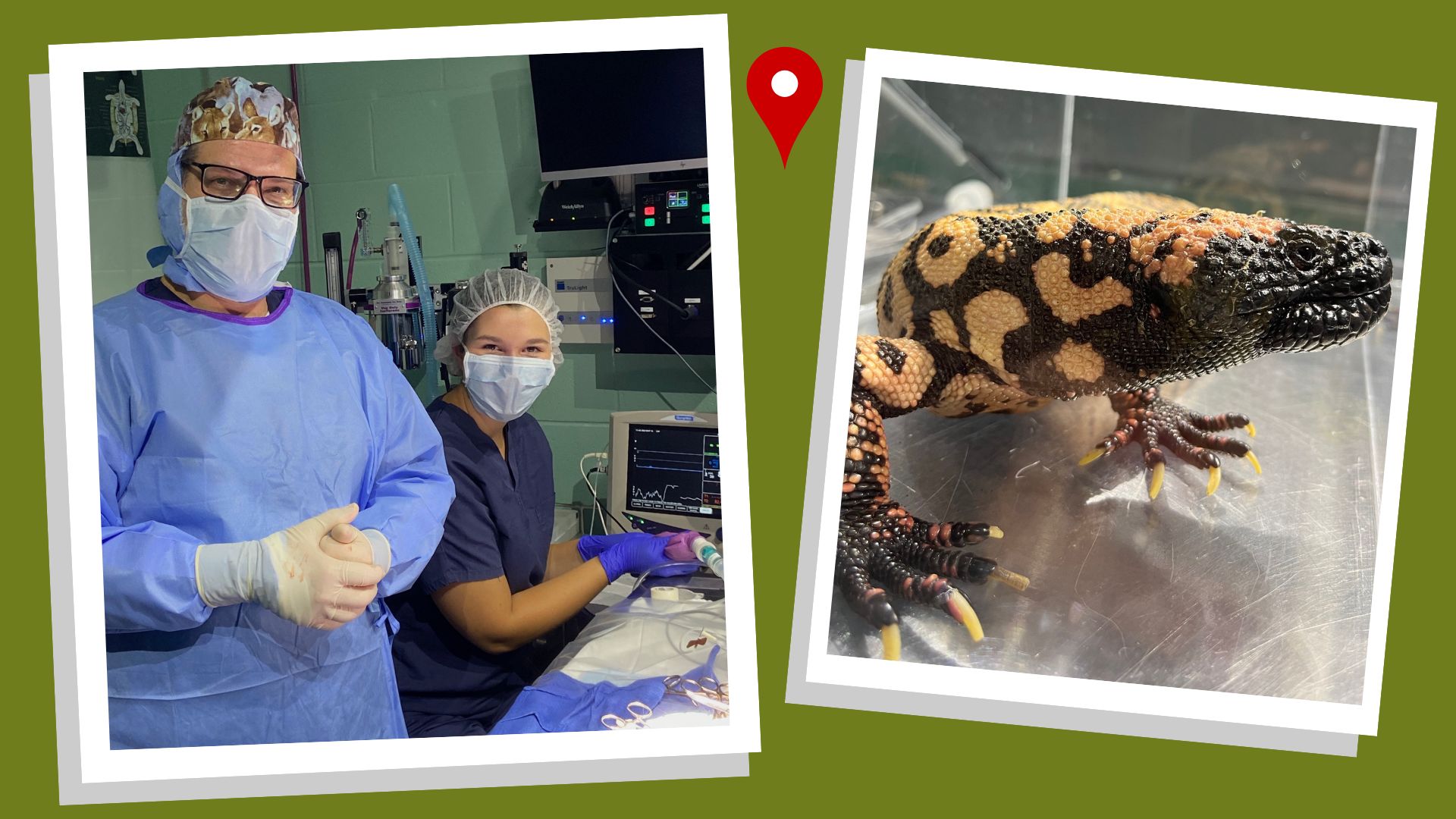

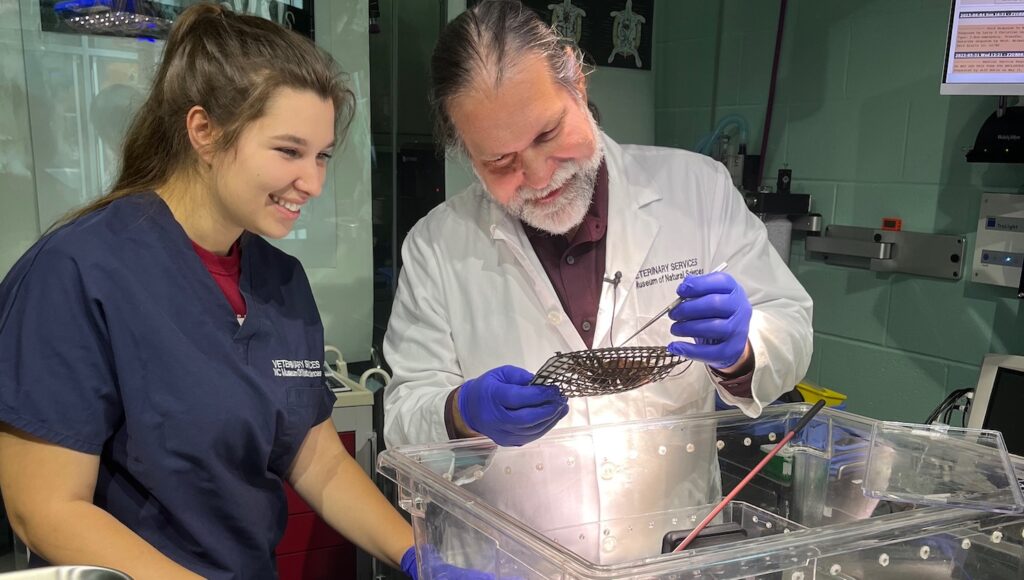

This week at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, I wrapped up my summer internship with fish and invertebrate examinations, as well as a final happy recheck on the Gila monster that I’ve shared several times during my internship.

The last time I mentioned the Gila monster, we were rechecking radiographs and tapping the coelomic fluid again to try to determine its origin. After several examinations to aspirate fluid from the coelomic cavity, there was little improvement externally. The fluid production appeared to be continuous, and details on both radiographs and ultrasound remained extremely obscured. Given that the effusion had remained static at best, progressive at worst, the team elected to take the Gila monster to exploratory surgery about two weeks ago, suspecting either neoplasia or an issue with the reproductive tract (follicular stasis, yolk

coelomitis, etc.).

During the surgery, I was responsible for supervising anesthesia and monitoring vitals, which can be difficult in reptiles. Between the Doppler probe, a pulse ox and a temperature probe, I was able to get a good picture of how the patient was doing and what plane of anesthesia she was experiencing.

Once the inside of the coelomic cavity was visualized, it became very clear that the ovaries were extremely enlarged and cystic, taking up almost the entire coelom. All the vasculature supporting the ovaries and oviducts was ligated and the entire oviductal tract was removed, a process called a bilateral ovariosalpingectomy. This was the best case scenario for our patient, since the reproductive tract can be removed easily and will likely be curative in this situation.

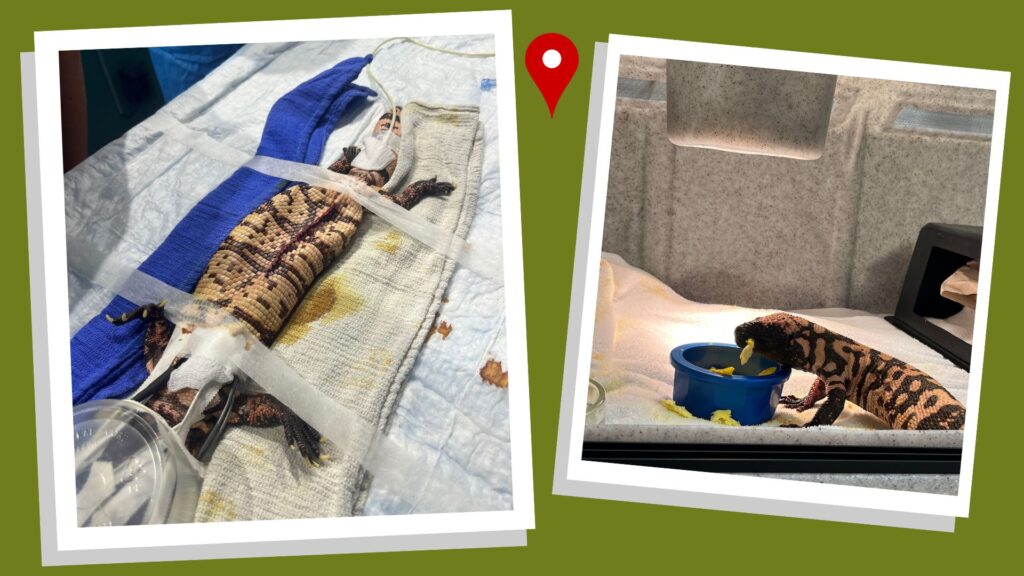

In the photos, you’ll see how deflated she appeared after the procedure, with the removed reproductive tissue weighing 37% of her pre-op body weight! She recovered from anesthesia beautifully and was up and walking within 10 minutes of extubation, which is excellent for a reptile. We’re now two weeks post-op and she is back to normal activity levels, eating and defecating normally, with an incision that appears to be healing well. Histopathology is still pending on the reproductive tissue that was removed, but everyone here is very happy with her recovery.

I was thrilled to be able to participate in such an interesting surgery, as well as follow this patient from her initial presentation all the way through to surgical intervention and recovery. I can’t wait to apply everything I’ve learned here to future cases and my career as a whole, and I’m incredibly grateful to the veterinary staff at the museum for the opportunity to spend so much time learning alongside them.

THURSDAY, JULY 6, 2023

Last week at the the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, I had the opportunity to work with some familiar faces, including our Gila monster from the first week of my internship, the American alligators again and some lesser hedgehog tenrecs that I assisted with as an undergraduate intern!

The Gila monster is doing well but has ongoing coelomic effusion whose cause we haven’t quite pinned down. During this week’s exam, we tapped the fluid again for repeat cytology and culture, collected blood and took more radiographs. The next step is a GI contrast study, with exploratory surgery on the table as a possibility if that doesn’t reveal a cause.

I swear the alligators have grown since I last saw them two weeks ago! We did a quick tank-side examination as a final recheck before transfer, and Dr. Dombrowski gave me the opportunity to practice capture and restraint of the second alligator. I definitely got splashed a bit, but now I’m more comfortable with crocodilians and safe handling!

The last thing I wanted to share is information about one of our lesser hedgehog tenrecs. These animals are named for their resemblance to hedgehogs but are actually part of a very unique family that is found in Madagascar, parts of mainland Africa and the Comoro Islands. Like the lemur species found in Madagascar, the tenrecs are a family with extreme diversity, all believed to have descended from a common shrew-like ancestor. Lesser hedgehog tenrecs are primarily insectivorous, although they do opportunistically feed on other things. They also undergo torpor for three to five months during the winter, similar to the mouse lemur. The museum has three lesser hedgehog tenrecs, and all three received clean bills of health during their exams.

I’ve included two photos of me with the same tenrec, one from my undergraduate internship

and one from this week. One thing I’ve really enjoyed about this summer is the opportunity to

follow up on patients I remember from my time here as an undergraduate! I’ll be back next

week with the next update!

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 20, 2023

Last week at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences was all about spiders! I was able to participate in wellness examinations on two of our resident tarantulas, as well as the final preparations of the brand new special exhibition that opened Saturday, “Spiders: Fear to Fascination.”

Invertebrate medicine is a relatively new field and is constantly evolving. Many people don’t

even realize that spiders can be treated by a veterinarian! Evaluation of spider health includes

watching the animal move; assessing diet, appetite and habitat factors; carefully examining all surfaces of the body; and scoring body condition. Sick or injured spiders can receive antibiotics, antifungals, fluids, and/or topical treatments, just like other animals. They can even be anesthetized with inhalant anesthesia for closer examination or procedures.

Both of the resident tarantulas we examined are females, around 10 years old. Females live

significantly longer than males, so these spiders are around the halfway point of their lifespan.

They both appeared to be in good condition, so we hope to have them around for the next 10

years or longer!

Another big part of last week was checking out the exhibit before its grand opening to the

public. Before going on exhibit, these spiders were cared for in quarantine and given multiple

quarantine exams by the veterinary team. We got to visit them on exhibit during the press

and staff opening, as well as check out the rest of the exhibit. It’s incredibly interactive and informative and was overall a ton of fun!

I learned a ton about spider anatomy and physiology this week, and I hope to work with more invertebrates in the upcoming weeks!

FRIDAY, JUNE 9, 2023

This week at the Museum, I had the opportunity to examine two juvenile American alligators

before they are transferred to another facility! These alligators are almost 2 years old and

have been ambassador animals here at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences since 2021.

When they arrived, they were hatchlings (less than a foot long from nose to tail tip), and they’ve more than tripled in size in the last two years. Although I’m a longtime fan of Steve Irwin, I’ve never done any crocodilian wrangling myself, so it was very exciting to learn about handling these animals. Even at 3 feet in length, they’re very strong, and you definitely wouldn’t want to be bitten by one! Luckily, our two patients were very easygoing on the table, with minimal attitude.

During our exam we checked everything from nose to tail, including a peek inside the mouth

while they gave a warning hiss. Alligators have the ability to regrow teeth that they lose

crunching on prey, and both of ours have a fully equipped mouth. I also made sure to palpate

the coelom thoroughly, since one of these alligators previously swallowed a piece of substrate and had to undergo GI contrast radiology studies to make sure they weren’t obstructed. Luckily, I didn’t feel any foreign bodies today.

Alligators also have a very well developed nictitating membrane that sweeps across the eye from the medial canthus. Right, drawing blood from the ventral tail vein of one of the alligators for routine bloodwork.

After a complete physical exam, the last step before giving them a clean bill of health was to

collect some blood from the ventral tail vein for routine bloodwork. This venipuncture site is a

good option for blood collection in alligators that are small enough to be flipped over and

restrained. We also will be collecting fecal samples from these animals before transferring, in

order to screen for Cryptosporidium and other GI parasites.

Overall our alligators look great, and I absolutely loved the opportunity to work with them! My

inner child was over the moon the entire time. Exotic and zoological medicine is a truly a dream come true for me, and the summer is flying by. I’ll be back next week with another update!

FRIDAY, JUNE 2, 2023

This week at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, we performed wellness examinations on three tiny little poison dart frogs, all of whom belong to the genus Dendrobates. In the wild, these diminutive frogs secrete a toxin onto their skin to defend themselves from predators. They sequester this toxin by feeding on toxic insects so in captivity they are no longer “poisonous” at all!

When performing exams on amphibians, it’s important to minimize handling to avoid raising their body temperature or damaging their mucous coating. For that reason, our frogs were placed in plastic bags for a short time while we examined their overall body condition and measured their heart rates via Doppler ultrasound.

After the exam, they were placed in shallow dechlorinated water to cool them off and replenish their moisture.

These frogs are actually not an aquatic species, but they do live in the rainforests of Central and South America, with high humidity and high levels of precipitation.

For those following along from last week, our Gila monster is doing well! The culture results came back with no growth, and a cytology of the coelomic fluid was most consistent with a transudate. As I learned in physiology class last year at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, a transudate can be caused by increased hydrostatic pressure or decreased oncotic pressure within capillaries/tissue.

The root cause of our Gila’s effusion is still unknown, but we’ve been able to rule out infection. The patient is eating and defecating normally and is moving around comfortably. We have repeat radiographs and a recheck exam planned for next week!

FRIDAY, MAY 26, 2023

Hey, everybody! My name is Emma, and I’m a rising second-year student with an intended focus in zoological and wildlife medicine. This summer I’ll be sharing what it’s like to work as a veterinary intern at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences! I previously interned at the museum as an undergraduate (and loved every minute of it), so I’m super excited to be back as a vet student to learn even more about captive management and exotic medicine. I also will be stationed at Turtle Rescue Team at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine on Mondays, intaking new cases and helping teach the undergraduate interns about wildlife rehab and chelonian medicine.

This first week of my internship, we hit the ground running with a few routine wellness exams, as well as rechecks on a few animals in the collection with chronic conditions. I also had the opportunity to care for some spiders that are in quarantine before going on exhibit. Strict quarantine protocols are an incredibly important aspect of managing zoos, aquariums and museums because diseases and pests can spread through a collection very quickly.

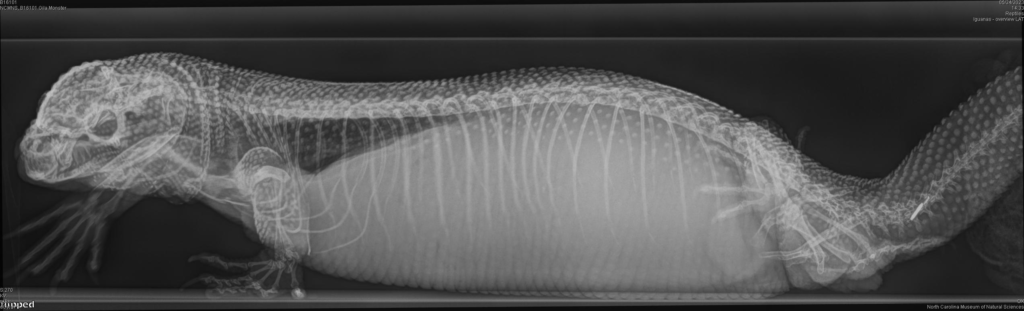

My favorite part of this week was definitely the opportunity to observe and assist with an examination on a Gila monster, one of the only venomous lizard species in the world! Because this is a venomous species, only trained staff can handle them, and we used a large sealed tube to take radiographs.

This particular Gila monster has been looking very round in the middle, despite its tail and limbs looking normal or even a little decreased in body condition. The lack of organ definition on radiographs led our clinicians to believe that there was either significant fluid accumulation in the coelom or a large space-occupying mass. Although we had previously been unable to aspirate any fluid, this time we collected about 20ml to send out for culture and cytology at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. Hopefully we can get some answers to the Gila monster’s condition soon with the help of these diagnostics. In the meantime, we can increase comfort by aspirating fluid to reduce pressure in the coelom.

I’ll be back next week with more interesting cases from the Window on Animal Health and hopefully an update on our friend the Gila monster!

- Categories: