Breaking Barriers: NC State’s Path to More Inclusive Veterinary Medicine

Without hearing a word, Imani Anderson was told veterinary medicine didn’t want her.

Like any proactive pre-vet student, Anderson aimed high. While studying at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, she was initially interested in equine medicine, so she looked for an internship in the horse capital of the world: Kentucky.

While reviewing an equine facility’s website, under “requirements” it noted that students shouldn’t apply if they “have a beard, have locks or any other unkempt hairstyle,” says Anderson.

“After I saw the statement, I looked through all of their pictures on their website. They had no people of color anywhere,” she says. “I said to myself, ‘Well, I guess I should have known better than to apply.’ And I shouldn’t ever feel like that.”

The incident was the first time Anderson felt discriminated against just because of her hair. It felt like an automatic cutoff for people of color in veterinary medicine.

Suddenly, Anderson, who had considered a career in veterinary medicine as early as elementary school, felt like there was no point to even try. Anderson called her mom who talked her off the ledge.

“I told her that it was definitely discouraging because this is the kind of field that I’m going into,” says Anderson. “Knowing the statistics at the time, there were a little over 1% of African Americans in the field. It was like, what am I doing here?”

Her mom told her to keep going. Anderson refocused. She started going out more to NC A&T’s farm, learning more about agriculture, spending time with dairy beef, swine and small ruminants.

Anderson found a possible answer to what she was doing here. Now, she’s a member of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine class of 2025.

“I got this bigger and deeper connection with veterinary medicine because it started teaching me more about small farmers and rural communities,” she says. “And that’s an area in veterinary medicine that honestly needs a lot more assistance than anything.”

Every veterinary student has their own story, and many stories are similar to Anderson’s.

For too long there have been barriers to veterinary medicine for historically underrepresented individuals, especially because of racial and ethnic identity. These barriers have ingrained overwhelming sameness in the profession. There have been decades upon decades of underrepresented students feeling a deep lack of support and understanding.

In many instances, underrepresented students first see a veterinarian who looks like them when they start undergraduate studies — or veterinary school. They see one on TV before they see one in person.

Underrepresented students head to class, walk by decades of framed portraits of veterinary school class composites and can often count the number of students of color on one hand.

For too long, stories like Anderson’s have been common. At NC State, the story is changing.

A Breakthrough Year

When the NC State CVM class of 2025 met for the first time at orientation in August, it felt different.

Under a tent on the campus’ front lawn, masked students met each other for the first time, and orientation was streamlined a bit to reflect COVID-19 safety precautions.

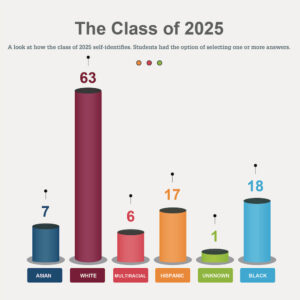

It looked different, too. The class of 2025 hit a high mark at the NC State CVM for the percentage of underrepresented minorities in veterinary medicine within one class. Among the class, a record 37% out of the 99 current class of 2025 students identify as something other than solely white. That number includes a record 18 who identify in some part as African American.

The makeup of the class of 2025 also reflects the wider scope of URVMs. As defined by the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges, historically underrepresented populations in the field include those “disproportionately impacted due to legal, cultural, or social claimed impediments in the United States,” including those disadvantaged because of their gender, race, ethnicity, as well as geographic, educational and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

Fostering a veterinary profession reflective of the world around us has been slow, but progress is being made.

Since the first black student, Tracy Hanner, was admitted to the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine as part of its second class in 1982, the total URVM population at the school has gone from just a few students each year at the most to an average of 25% from the class of 2018 through the class of 2024. The average was just 11% for the four CVM classes before 2018.

During the past 15 years, the number of URVM students in the United States has increased by 11%, according to the AAVMC. Other figures are not as encouraging.

Though the number of racially and ethnically underrepresented students in veterinary medicine has doubled since 2005, according to Insight Into Diversity, the number of Black vets in America dropped from 2.1% of the total veterinary population in 2006 to below 1% in 2019.

When The Atlantic called veterinary medicine the “whitest profession” in the United States in 2013, 92% of veterinarians were white. Eight years later, it’s still 90%.

“It would be a mistake to think that numbers alone tell the story or that we should feel secure that we’ve done everything that needs to be done — far from it,” says CVM Dean Paul Lunn. “This is a vital step that we’ve been able to recruit a class like this. Nevertheless, we’ve made a promise to them that they’re going to find an inclusive environment where they feel accepted, where they feel that they can thrive and where they feel that they’re safe.

“We need to be a place where they can be themselves.”

At the CVM, fixing the problem didn’t happen simply by upping the numbers. It was about acknowledging and understanding that there was a problem in the first place.

Walking the Walk

Finding a school that fostered an inclusive atmosphere was her biggest factor in choosing a veterinary school for the class of 2024’s Nia Powell.

As an undergraduate at the University of Missouri at Columbia, she experienced racial unrest firsthand, as students led several protests highlighting systemic inequity. One event was called “Racism Lives Here.”

“I mean, I’ve been Black all my life. Obviously, I’ve experienced this stuff forever, but that was the first time I saw it from a standpoint where I realized that people really didn’t want me there,” says Powell. “I refused to go to another environment where I was going to have that experience.

“I needed to go someplace where I was not going to be the only person who looks like me and where people were going to appreciate that. People can say that they support diversity all day long, but I do feel like it’s happening at NC State. I’ve never felt less than here.”

Over the past 15 years, the CVM has done many things other veterinary schools have done to address diversity and inclusion. There have been scholarships and recruiting initiatives. There have been book clubs and discussion circles and speakers.

Clubs have been formed for URVM students to support each other. Last year, the college launched the inaugural Fall Program on Race and Representation.

Something else happened 15 years ago: Allen Cannedy joined the CVM as its director of diversity and multicultural affairs. While many URVM students share stories of adversity and systemic roadblocks, their stories at NC State also often include Cannedy.

Much of the slow but steady progress toward inclusion at the CVM can be attributed to Cannedy.

He helped push for an admissions committee that had URVM representation itself. He advocated for eliminating the GRE requirement to be considered for admission, after studies over the decades have shown that as an admissions tool for professional degree programs it disadvantages minority students because of built-in racial, gender and socioeconomic biases, according to the AAVMC.

The NC State CVM no longer requires GRE scores for admission, but 75% of AAVMC-affiliated schools in the United States still do, says the organization.

Another long-standing barrier for URVM students: required experience hours. Previous veterinary medicine experience hours required for CVM admission were as high as 1,200. It was gradually cut down over the past decade — in half, then down to 400 and finally down to the 200 required hours for admission today.

That change impacted many students. Anderson at one point didn’t have a car and was helping to support her mom, who raised her alone. She had to find a job that offered experience but also one that paid. That often meant working at an emergency room every weekend from 4 p.m. to sometimes 4 a.m.

The class of 2024’s Christine Zavala, who identifies as Latina, started working in high school as soon as she was old enough so she could begin saving for college — and to pay for a car so she could drive herself to NC State for undergraduate orientation. As a student, she had to continue working to help pay for school.

“I didn’t grow up with a lot of money. Because of that, I couldn’t just go volunteer for hours a week because I needed to be at work,” she says. “I couldn’t just work for free, like a lot of non-people of color can do.”

When URVM students’ voices aren’t being heard, Cannedy listens.

He has forged numerous relationships with students over the years, often inviting them to shadow him on farm calls he makes as a small ruminant veterinarian. Sometimes during the calls, they talk about inclusion in veterinary medicine. When they do talk about it, he has always been honest.

“I remember asking Dr. Cannedy about what diversity was like at the CVM and he said, ‘It’s not great, but we’re working on it,’” says Zavala. “I understood that. There’s so little representation of Latin people in vet med. It’s hard to find a mentor that understands what you’re going through. He’s really who I talked to a lot about it.”

There was a time when Cannedy knew every single URVM student who entered the CVM. Now, he doesn’t. That’s a good thing, he says.

“It’s not made-up that if you give an underrepresented individual that is capable and competent and that deserves to be here, a chance to be here, that they’ll be successful,” says Cannedy “Now we’re not just talking about that, we’ve done it. So let’s see just how powerful it can be.”

When Lunn first arrived at the CVM in 2012, the first thing Cannedy asked him was what he planned to do to address the lack of diversity and inclusion. A further internal change within the CVM community worked in concert with substantive admissions changes was a further internal change within the CVM community. In 2016, the college committed to becoming a values-driven community, with one of four shared core values being “we practice inclusivity.”

“We know that it is our diversity that makes us stronger,” the statement notes.

They aren’t empty words. A big part of the shift was helping the campus community understand how a history of inequity had led veterinary medicine to this point.

Discussions about inclusion have long been a part of orientation, but starting in 2016, a new house system brought together students, faculty and staff into different, diverse “houses.” An Office of Diversity was created and a diversity committee was formed to not just discuss issues of inequity, but take substantive action (one recent creation: a bias incident report system).

As a rash of incidents shined a harsh light on inequality in America over the past few years, it led to further reflection on veterinary medicine’s crippling sameness.

When violence repeatedly occurred —the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, for example — leadership acknowledged the pain but also took a stand.

“This horrific violence against Black people degrades us. It can have no place in a civilized country and we must speak out against it at every turn,” Lunn said in a publicly released video statement.

Since then, through emails and town halls, Lunn has regularly addressed the type of hate against African Americans, Asians and the Latinx community that many students experience.

“You can hear his emotion,” says Safari Richardson, a member of the class of 2024 who identifies as Black. “Just knowing that we have a dean who cares about these things, I feel like that sets the overall tone of the university. Because I feel like if the dean doesn’t say anything, then they probably don’t care. And then the rest of the university probably won’t care enough to make any changes.”

Feeling Alone

At the traditional white coat ceremony, the incoming CVM class is welcomed into the veterinary field. A person of their choice — usually a family member, mentor, or friend — joins them on stage and places a white medical coat over their shoulders.

“My mother was there with me and her first thought was, ‘I don’t belong here,’” says the class of 2022’s Daniel Mejia, who was born in New York and identifies as Latin American. “She was around all these people who come from families of doctors and are people of higher education. My mom’s a housekeeper at UNC Hospitals. She was a single mother. She had to make a lot of sacrifices, and without those sacrifices, I wouldn’t be here.

“When she said she doesn’t feel like she belongs here that made me feel the same way, too.”

Statement on diversity and inclusion at the CVM.

From his first day on campus, Mejia didn’t know how things would be for him at the CVM, but he felt a sense of excitement right away when his class received their house system assignments. It was that type of enthusiasm, he says, that drew him to NC State in the first place. “It almost felt like I wasn’t going to be treated any different, that everyone is just kind of the same,” he says.

Now beginning his final year at the CVM, Mejia has felt welcomed at the school and within the Latinx student community.

He co-founded the Latinx Veterinary Medical Association student chapter on campus, where students from Puerto Rico, Mexico and other countries, as well as those who identify as white, Black and Asian Latinx, can support each other, talk about what it’s like to be a veterinary student in America when English is not the primary language for some students, discuss shared perspectives on classism and social economics — or just take a break from classes together.

He says he doesn’t feel alone or unwanted, spending a good amount of time being open and proud of his background — and sharing it with others. Through the years, it’s the chats with students, faculty and staff where he brought up issues with his identity and concerns about inclusion that made a difference. In those little moments, there was and still is comfort in having people who are willing to listen even if they may not entirely understand.

“Once people start seeing people like them in this field, in this community, that they can reach out to for mentorship and help, people are not going to feel alone and feel guilty for that,” says Mejia. “I think it will take a while before we see those changes.”

That lack of representation — and having others around them who can relate to and share their experience — has kept many URVM students away from the field.

Anderson grew up in Raleigh with several over the years and never saw a minority veterinarian until a few years ago. One of the first she met was a 2015 CVM graduate, Andrea Gentry-Apple, one of her animal sciences professors at NC A&T. When Richardson shadowed at her first veterinary clinic in Greensboro, all of the veterinarians were white, all of the veterinary technicians were white and all of the receptionists were white. The only person of color was the cleaning lady, who was Black.

Even students who come to NC State from a historically black college or university have felt isolated before. The class of 2025’s Malik Chennault went to Howard University and majored in biology.

“When I would say oh, I’m wanting to go be a veterinarian, everyone would say, ‘What? Like, what? I’ve never met an African American vet before,’” he says.

When he was accepted to NC State, Chennault first reached out to Cannedy and then connected with Powell, who gave him a campus tour. During that tour, he met a Black CVM clinical professor, Mariea Ross-Estrada as well as several other Black students.

“I was floored. I said maybe this is the place for me,” says Chennault. “My mindset coming to vet school was purely based on education. I knew that outside of Tuskegee University, diversity wasn’t necessarily a strong point anywhere. My goal was to be a vet, so at the end of the day, that’s all that really mattered. If I’m going to be the only Black person, that’s OK.

“And so to come here and see it exceed the status quo so much, it just meant more than I could say. It gave me hope.”

Though more faculty and staff inclusion is a long-term goal at the CVM, having supportive and empathetic teachers on campus like Ross-Estrada and Liara Gonzalez, makes a tremendous impact.

Gonzalez, an associate professor of gastroenterology and equine surgery, relates to the experience of many of the college’s URVM students. Gonzalez has long felt as though not much had changed on the inclusion front from when she was in vet school, even though she graduated in 2006.

“I feel like maybe finally we’ve broken through. I feel like finally, we’ve been able to topple this wall where, despite a lot of efforts, we were only moving the needle a touch,” Gonzalez says. “And hopefully this means that we’ll see nothing but progressive improvements and advances in years to come.”

Gonzalez, who identifies as Latina and Jewish, grew up in the northeast corner of Connecticut where her family was the only Puerto Rican and only Jewish family in town that she knew of.

In veterinary school, she had trouble fitting in during her first year until she got to know a group of students who all happened to be Black, indigenous or people of color. They became her support system. They shared life experiences that were similar even though they were culturally different. That felt freeing.

“I could go into a large animal hospital and I could be surrounded by nobody that looked like me or anybody that shared similar experiences,” says Gonzalez. “But I knew that when the day was done, I could call up my girls and we could hang out and banter back and forth and talk about our days.”

Gonzalez committed to making the veterinary school experience easier for those who are different, making it more comfortable for those who feel singled out. She never wants to see a student feel like they have to hide parts of their identity or apologize for an accent. For five years, she led the CVM diversity committee.

“It drives me every day. It’s a responsibility,” says Gonzalez. “I’m appreciative that I can be here to serve as a sounding board for them. I had wonderful mentors, but it’s different when you have someone who has shared in those experiences and can share with you how they dealt with it all.”

When CVM students see someone who looks like them on campus, they see themselves in veterinary medicine.

Cannedy’s support was a big factor in Richardson coming to NC State. The first time Zavala saw a Latina vet was when she worked as a vet assistant in the cardiology service with Teresa DeFrancesco, professor of cardiology and ICU critical care. Working with her, Zavala says, made it feel possible that she could be a veterinarian, too.

And as the United States continues to diversify rapidly on cultural and racial lines, the need for wider representation in the veterinary community is palpable. More people of all races now own pets, including 65% of white households, 61% of Hispanic households and about 37% of Black households, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association. That includes a 44% increase of Hispanic pet owners and a 24% increase in Black pet owners between 2008 and 2018. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that jobs for veterinarians and technicians will grow by 16% by 2029.

“For an underrepresented minority student, seeing a minority faculty or staff member transforms their thinking in ways that you couldn’t imagine — and it can change the profession,” says Cannedy. “When anybody sees an individual that looks like them, that they can identify with, performing those duties and those procedures that they themselves want to do, that validates them. It did for me.”

An Inclusive Future

The class of 2025’s Hannah Wubbenhorst has long felt the lingering crush of feeling ostracized, even by people who she would consider part of her own community.

Wubbenhorst, who identifies as African American and whose dad is white and mom is Black, says she has shared with others what it has felt like being, “rejected as a multiethnic person who’s several shades lighter than average.” She shared that experience with fellow students during CVM orientation.

“Inclusivity is the buzzword these days, so it really comes down to the attitude of leadership for me,” says Wubbenhorst. ”Every place is going to talk about it, but it’s more about being proactive and taking into account what underrepresented minorities or people from different backgrounds are dealing with.

“That’s one thing I enjoyed about orientation. Regardless of who we were, regardless of how smart we seemed, or whether we were white or Black or Latina or Asian or whatever else, we all felt heard and we all had to kind of stretch and get out of our comfort zone. That’s not easy, but it felt real.”

Wubbenhorst almost didn’t apply to veterinary school. She saw others with more experience than she had and felt like she couldn’t compete. On the edge of waiting a year, she had lunch with Cannedy.

She told him that she didn’t think she could apply to vet school.

“And he looked at me and he said, ‘No, you should. Your experiences might not seem like enough, but you as a person are definitely enough and you can do this,’” Wubbenhorst says. “He was the one who convinced me, regardless of how inferior I might’ve felt in terms of those experiences and accomplishments, to still go for it. That there’s more to it than that.”

It’s that unrelenting support that will help increase inclusivity in the future. In 2005, a year after Cannedy began his diversity work at the CVM, the college admitted eight African American students, at that time the most diverse class the college ever had.

“It was extremely difficult for them because our culture, our community, was not quite ready to accept them for who they were,” says Cannedy. “It just honestly wasn’t. I won’t say that there won’t be some challenges in that area for this group of students to face, but they will not face it the way that group did back in 2005.

“We have come so far within our community of raising awareness and understanding and acceptance. Acceptance. Not tolerance, but acceptance.”

Lunn, who will step down as dean in January 2022, knows the fight for inclusion has just begun and won’t ever stop. The last thing the class of 2025 should do, he says, is send the college a message that it can relax inclusion efforts or the support it gives.

“I think this journey to inclusion is something we’ll be going down for a very, very long time to come. It’s something we have to be conscious of and work actively to address at all times,” Lunn says. “Inclusion and diversity will never be secondary issues. It will always be a priority within the college.”

And it will always be a priority for many of the college’s students. Almost all of the students we spoke with for this story are either currently involved in work to promote inclusion in veterinary medicine or plan to prioritize it as part of their careers.

Powell is the class of 2024’s diversity chair, serves on the CVM diversity committee and is a pre-veterinary adviser for the Black DVM Network, among other activities related to diversity. The college recently launched a regular series called Cope & Connect, an in-person and recently virtual space for BIPOC students held weekly and led by Laura Castro, director of CVM counseling services. Powell is pushing for such a safe space to become permanent. So is Gonzalez.

Zavala once served as a panelist for a Q&A with minority high school students who were interested in veterinary medicine. She said it only took 30 minutes to answer their questions, but it felt like those 30 minutes meant a lot of them. Zavala’s long-term goal: opening a low-cost clinic for underrepresented communities, where they can go to a vet who they know can speak their language.

“It’s one thing to have a diverse class and accept more diverse people, but that’s only half of what we need,” Zavala says. “We also need them to feel supported. It doesn’t do us any good to have people here if they don’t feel at home.”

Mentorship is a big part of Richardson’s daily life as a veterinary student. She frequently looks to connect with other students of color — and to tell them to keep going.

“Without the mentors I had, I couldn’t say that I would be sitting in front of you right now, having this interview, so I do try as much as I can to be a mentor,” says Richardson. “We can have difficult conversations, like what it’s like being Black and being Black in vet med. I always tell them that even though our field is not known for its diversity, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t people like you out there. It doesn’t mean that you can’t get through it. It doesn’t mean that you can’t succeed in vet med.”

Getting introduced to veterinary medicine early, says Chennault, is the best way to build representation in the future. So many minority students are not introduced to these professions, let alone ones who live in urban communities, he says, and improved access to public health education, in general, would also benefit so many students.

“Be the first, so you don’t have to be the last,” says Chennault. “And always, regardless of color, do what you want to do, be who you want to be. Always show people that you can do it, that it is possible for someone who looks like you.”

And Anderson knows that URVM students like her may long face the same type of barriers she felt when researching that equine experience in Kentucky. “It’s not worth your time,” “I didn’t know there were Black veterinarians,” “you’re not going to get in” — those statements will likely always be said. Whether they will actually be heard is another matter.

“I stopped hearing statements like those once I started working even harder to get in,” says Anderson. “It starts with you. If you want to be the change, you work to be the change.”

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine