App Created at NC State at the Center of Important USDA Plan to Track Swine

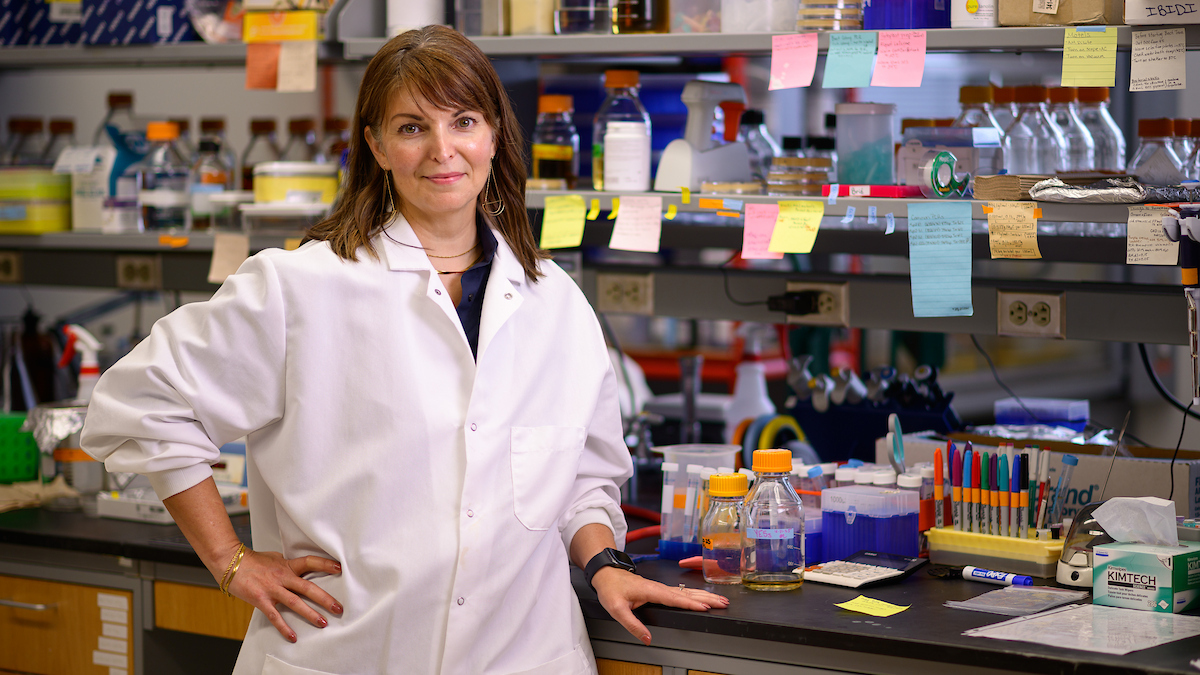

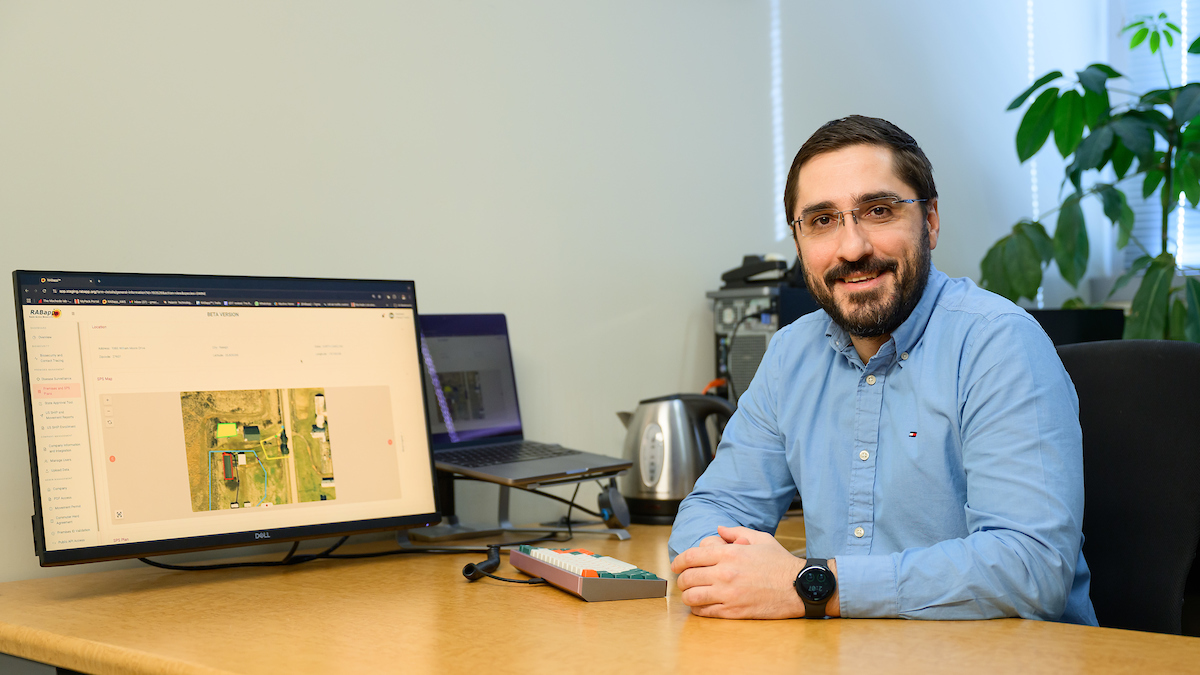

Dr. Gustavo Machado, associate professor of emerging and transboundary diseases at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, has led the research and the design of RABapp, which 15,000 swine farms across 23 states already have registered to use.

A cloud-based computer program developed at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is the critical component in a US Department of Agriculture plan to begin tracking the movement of swine across the United States next year to prevent the spread of deadly diseases.

The program, called the Rapid Access Biosecurity App or RABapp, allows farms to enter biosecurity and animal-movement data online so that state and federal authorities can better track and control outbreaks of swine diseases, including African swine fever, classical swine fever and influenza A. Though the USDA’s new initiative, the US Swine Health Improvement Plan, allows hog producers to become certified as disease-free, the app also has the capability to process information on cattle and poultry biosecurity and movements.

Dr. Gustavo Machado, associate professor of emerging and transboundary diseases at NC State, has led the research and the design of RABapp, which 15,000 swine farms across 23 states already have registered to use. Machado helped create a similar system in Brazil, his native country, where laws have required animal traceability for decades.

“To use RABapp, farmers need to sign an agreement to have access because their data is considered classified,” says Machado, who has a DVM and a Ph.D. in epidemiology. “Then they can get a biosecurity plan entered and reviewed by animal health officials, so that farms with biosecurity plans and movement data in RABapp can be certified. That’s why this program was created: to be able to secure the market and demonstrate to our importers that farms have what we say they have.”

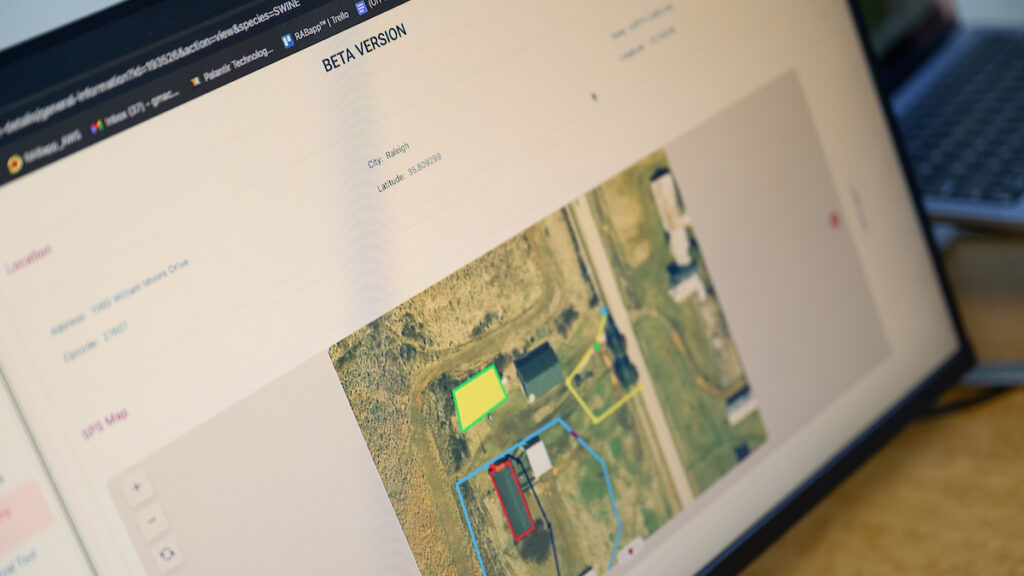

With more than 150 questions to answer and a map-making capability, the RABapp program provides the tools farms need to create a biosecurity plan. The finished map will show color-coded assets, such as red lines that no one can pass during a disease outbreak unless they’ve showered and blue lines where anyone can still go.

“We also ask what they do, such as whether they clean the vehicles when they come in,” says Machado, who also has researched how often diseases are spread through unsanitized trucks. “How do they handle doing a shower in and shower out situation during an outbreak? It’s quite key for curving disease dissemination.”

The farms also report the movements of their swine: what farms they came from and what facilities they’re going to. The program shows any farm that reports a disease outbreak in red.

“This is a breeding farm,” says Machado as he points to a red dot on his computer screen. “You see a lot of farms downstream from this farm, so you know these farms are probably infected because they are receiving piglets from that breeding site. If I wanted to be ahead of the curve, I would test these farms right away. If we wait too long, we have a lot of other farms downstream. Guess what? They’re also going to be infected.”

The USDA estimates there are about 23,000 commercial swine farms in the United States. The goal is for the USDA to codify that farms be registered and certified by the US SHIP program.

In creating and launching RABapp, Machado and his team of computer programmers have worked with pork producers, state veterinary health officials and veterinary practitioners across the country. In a novel partnership with the NC State University Department of Computer Science, Machado hires new master’s degree holders for two-year stints in his lab, giving them experience and fulfilling his programming needs.

“Everything in the RABapp program is two clicks away, max,” he says. “Our users are very happy. They always compliment us and say RABapp is very easy to use.”

North Carolina is the third-largest pork-producing state in the country, and the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine supplies most of the food animal veterinarians with whom each farm is required to contract. A farm’s veterinarian is the person who likely will create the biosecurity plan in RABapp, says Machado, who notes that NC State veterinary students focusing on food animal medicine learn how to build biosecurity plans.

Disease outbreaks can be costly for farmers. A single outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, for instance, can cost a swine farm upward of $600,000, Machado says. Losses from industry outbreaks of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome cost pork producers $1.2 billion annually between 2016 and 2020.

In theory, Machado says, the RABapp could help U.S. pork producers increase their sales because most countries that import pork products require proof of where the food came from.

“If there’s a crisis here, countries are going to turn and say, ‘So what is your traceability system?’” he says. “So, there is an urgent need to get most producers onboard.”