From an NC State Ruminant Research Project, Hannah Dion Reports

Students at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine have access to all kinds of internships, externships and research experiences during their four years of school. This summer, several students are sharing some of what they're doing and learning in real time.

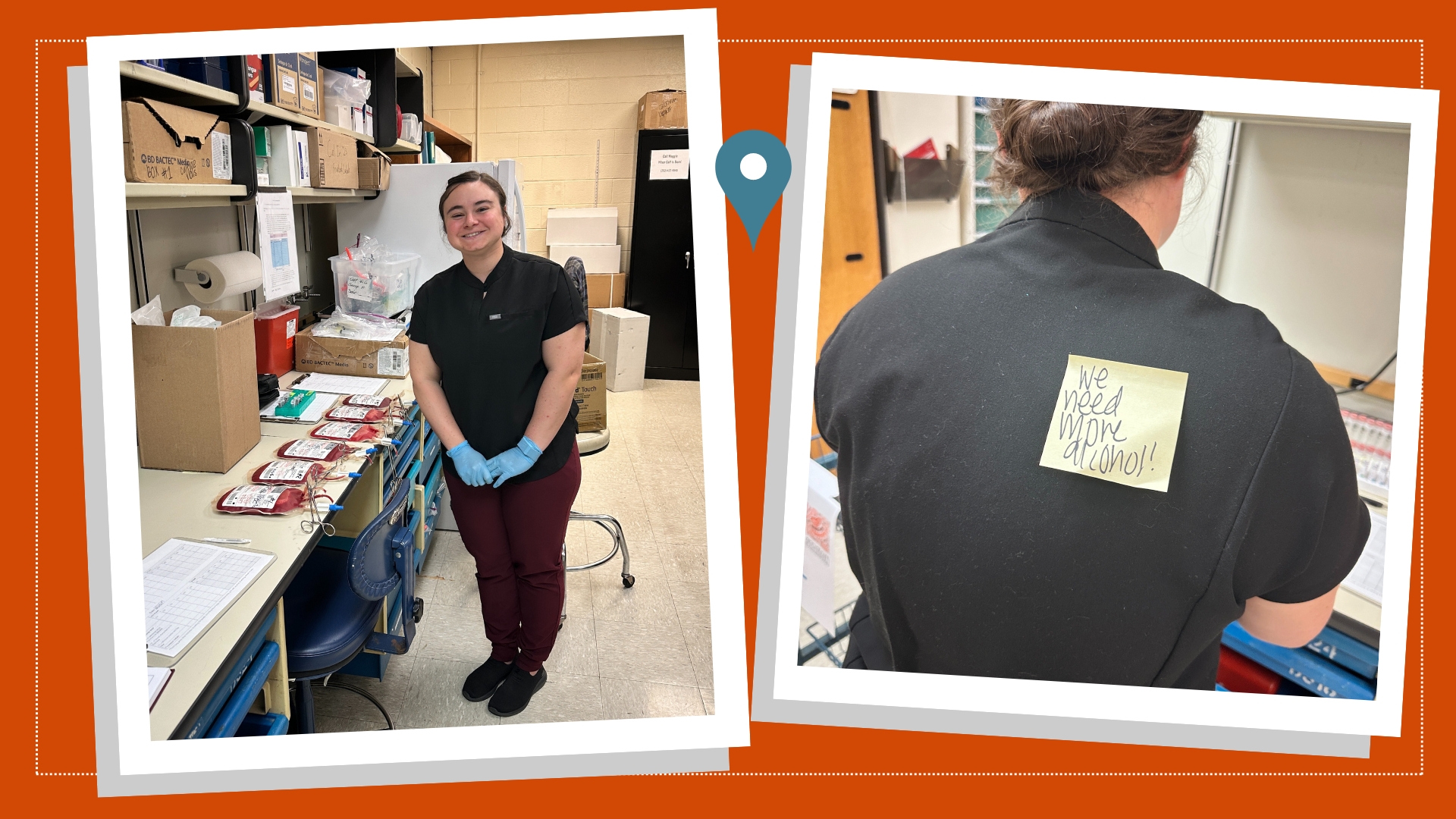

This past month has been spent performing laboratory tests on our blood bags. We used alcohol to clean the sampling ports on the blood bags themselves for weekly samples and needed more.

The most involved laboratory test has been the erythrocyte osmotic fragility test. Broken down, we are testing the stability of the red blood cells by exposing them to differing concentrations of NaCl and looking when the red blood cells undergo hemolysis, or burst.

The longest step of this process was the 45-minute incubation period.

Fun fact: Goats have the smallest red blood cells out of all our domestic species. Yes, even smaller than cats!

Out of the lab itself, we have been performing statistical analysis on our results and preparing our abstracts and presentations for the VSP Summer Lecture Series!

Through the VSP Program, the ruminant cohort has been performing multiple studies, including Dr. Jennifer Halleran’s, on campus. We have been able to assist them in collecting data and learn about their projects.

My lab partner, Lanie Phillips, took advantage of the opportunity recently to assist with baseline measurements for Dr. Halleran’s project (pictured below) designed to find the most effective ways to administer pain medication to goats with urinary blockages.

JUNE 6, 2024

Because internal parasitism is leading to a large number of anemic goats in the southeastern United States, hospitals throughout the area are performing blood transfusions frequently to treat the issue. Clinicians can either give fresh goat blood as a transfusion or store it as refrigerated whole blood or packed red blood cells. Storing blood is more practical for late night and emergency situations as the blood is easily accessible and available for immediate use.

However, there is no consensus on best practices when it comes to storing goat blood, the duration of storage and the effects on the blood product preparation itself, as well as administration methods, using a fluid administration pump or administrating it through gravity flow.

This summer we are trying to find out how long we can safely store and use goat blood as either whole blood or packed red blood cells without risking red blood cell health, identifying whether there is any bacterial contamination or growth within the blood bag over time and trying to establish the best administration method for these blood products to our patients. This study will improve blood transfusion medicine in small ruminants as a whole.

On May 28, Dr. Lisa Gamsjaeger, veterinary technician Lanie Phillips and I went out to the Small Ruminant Educational Unit, which undergraduate veterinary students use for their animal science classes and labs, to collect baseline bloodwork and FAMACHA scores to sample and enroll goats that weighed enough to collect 900 mL of blood from them for our study.

A few facts:

- The farm itself is a small working farm, breeding sheep and goats for NC State students to work with.

- The Large Animal Hospital uses these goats for their internal blood bank because they are healthy, appropriately vetted, up to date on vaccinations, routinely weighed by the staff, friendly and used to humans.

- Our project is focusing primarily on blood banking and blood transfusion techniques for small ruminants, so it was appropriate to use these goats, as they are already used by the hospital for this purpose, and the farm’s manager, Hannah, was happy to assist us in any way that we need.

- This day we identified eight goats that met our criteria and enrolled six on the following day.

FAMACHA scoring is an important part of our process. FAMACHA uses the mucous membrane color of the lower eyelid (conjunctiva) to assess the amount of red blood cells of small ruminants. A high FAMACHA score indicates anemia, which is likely caused by parasites and requires appropriate deworming. Internal parasites, most importantly the barber pole worm or Haemonchus contortus, can cause severe anemia in goats. However, they often go undetected and untreated unless the level of parasitism affects the goat’s day to day life or causes a level of anemia that makes the goat display overtly negative clinical signs. Internal parasites are the biggest cause of health and production losses in small ruminants in the United States, so regular monitoring of the parasite burden through fecal examinations and FAMACHA scoring should be performed to detect the presence of these worms early.

One of the best things about the Veterinary Scholars Program this summer is that there is opportunity to assist and learn from other projects that are going on in your cohort. In the food animal/large animal cohort, there are several other projects with multiple species. Dileydis Soto Montes, NC State CVM class of 2027 working with Dr. Kelley Varner, and Maggie Mooring, class of 2027, working with Dr. Jennifer Halleran, volunteered to help us get hands-on experience with the goats.

Anna Flynn, a Ph.D. student focusing on calf health and the fecal microbiome and how those are impacted by the feeding of waste milk, and research assistant Hakeem Jenkins also were part of the goat team.

First we identified the goats whose collected baseline blood work was satisfactory to participate in our project and that could withstand a 900mL blood donation. We had marked the goats sampled the day prior with a purple stripe on their shoulders. Then, we conducted a full physical examination to confirm that the earlier results were still true. Then we clipped the area on both sides of the goats neck, over their jugular veins, and aseptically prepared the area before collecting a preliminary blood sample to run more extensive baseline blood work. This blood work would give us a baseline against which to compare future values from the blood transfusion bags themselves and what we are testing on them.

Lastly, we collected the blood donation for the blood bag! Everyone involved, under the guidance of Dr. Gamsjaeger, got the experience of collecting a blood donation via the blood bags.

Teamwork was essential during this entire process! Everyone had a role that we rotated through: restrainers, collectors, blood bag mixers and weighers, material runners and documenters (and, of course, photographers!). Then we returned to NC State College of Veterinary Medicine to start our initial processing, organizing and Day One testing.