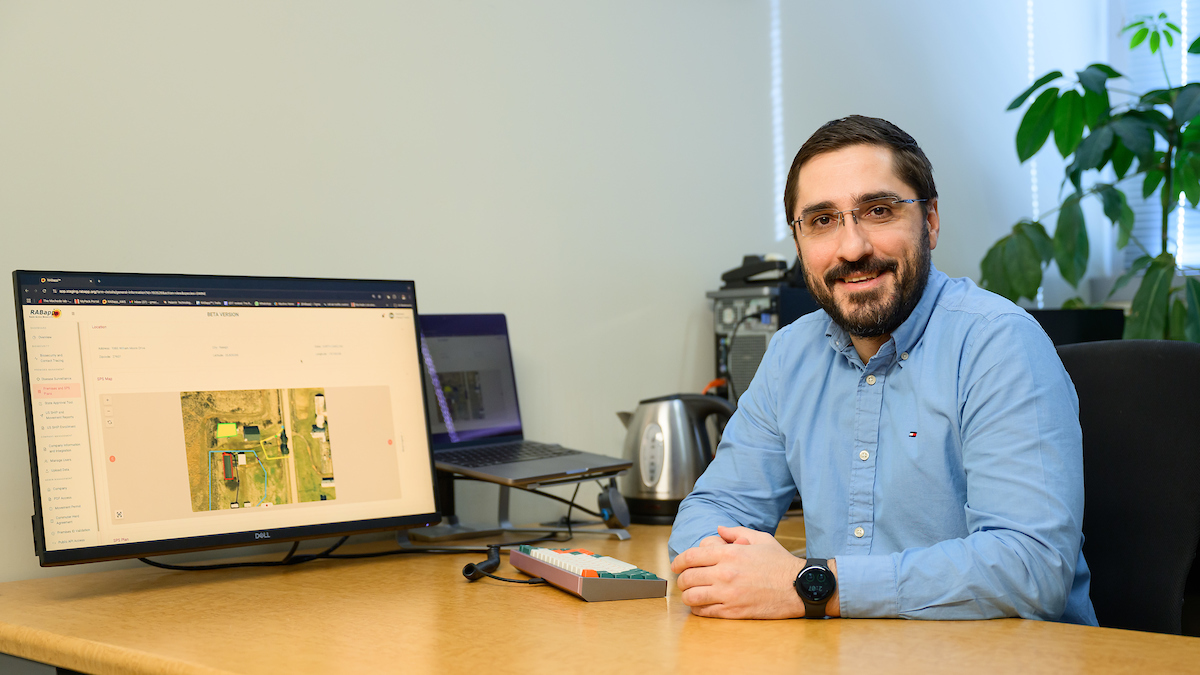

With New Scholarship, CVM Alum Hanner’s Strong Voice for Inclusion Grows Ever Louder

As much as he could let himself, Tracy Hanner became used to hearing racial slurs.

Graduating from high school in North Carolina two years before desegregation, he often heard the words wherever he went. They flew around the corners of his high school hallways in Chatham County as he walked past groups of white students.

The words hit him in the face, but he didn’t wince. He pretended to not hear them at all.

He wasn’t surprised by the questions he was asked after starting veterinary school.

“How’d you get in the class?” “How smart are you?” “Whose place did you take?”

One person asked if there was a Black national anthem, as though America’s national anthem didn’t apply to him.

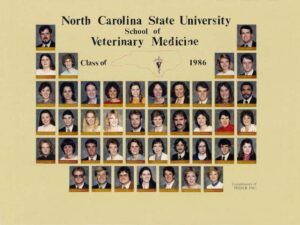

Hanner was the first Black student at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, the only one in the 40-member class of 1986, the college’s second class. At the time, there were very few veterinarians of color in the United States and even fewer were CVM faculty.

One CVM student made a difference just by becoming Hanner’s friend.

Since Hanner was commuting about 60 miles a day, every day each way, from his home in Bear Creek, N.C., to the CVM, Bobby Schopler offered Hanner a room in a home on Jones Franklin Road where he other vet students were living. Schopler soon called him “T.”

And right after the CVM urged support of an endowed scholarship in Hanner’s name last month on Juneteenth, Schopler gave Hanner a call.

“He said, ‘You know, I didn’t realize how tough it was for you,’” Hanner says. “He said, ‘We would just go places and I never thought about how you felt about the places we went to, how you had to think about it, if these places were OK for you. But I didn’t have to worry.’”

Schopler also told his friend he would contribute to the scholarship, which will support underrepresented minority students attending the CVM. He wasn’t alone. A goal was set to endow the scholarship, launched by the North Carolina Association of Minority Veterinarians (NCAMV), at $50,000. The college announced last month that it would match up to $25,000 in public contributions.

It was estimated it would take a month to hit that goal. It took a week.

“Our college is deeply honored to count Dr. Hanner as one of our alumni. He is an inspiration to many members of the Black, indigenous and people-of-color communities,” says CVM Dean Paul Lunn. “The scholarship established in his name provides vital support to underrepresented minority students at NC State.

“The generosity of donors has shown the best side of our community at a time when we must continue to strongly demonstrate our commitment to anti-racism.”

Alumni contributed, CVM faculty and staff contributed. Community members gave in amounts big and small. Those who knew Hanner and those who had never heard of him contributed as a way to honor his nearly 40-year legacy of making tangible and vital differences in diversity and inclusion, not just at the CVM but in veterinary medicine as a North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University professor and mentor. The scholarship is now over $50,000 and counting.

“All I wanted to do was go through veterinary school and then start a career,” says Hanner. “But then that changes when you see there is an issue that is bigger than you but that you can do something about. But this is not about me; it’s about the greater struggle. It’s about the greater reality of changes needing to take place.”

Agent of Change

The Tracy Hanner DVM Scholarship Endowment is the third at the CVM to support underrepresented minority veterinary students. The first, also created by the NCAMV, was the Dr. Alfreda Johnson Webb Endowed Scholarship, launched in 2016 and named for the first Black woman to graduate from a veterinary school. Webb was also Hanner’s mentor, a North Carolina A&T State University professor who also helped guide the CVM in its early planning stages.

The following year, the CVM and Pembroke University announced the University of North Carolina Veterinary Education Access program, designed to make veterinary education more accessible to minority students, especially those from a rural background. Recently, North Carolina A&T joined the program.

The money is significant. Though the CVM is considered among the most affordable institutions of veterinary education in the United States, cost is a hindrance for many. But the scholarships go beyond financial help. They showcase the CVM’s ongoing, ever-evolving efforts to encourage inclusion at the school and in veterinary medicine.

The scholarships, says Hanner, are part of the solution.

Veterinary medicine is still relentlessly homogenous, though in the past 15 years the number of underrepresented minority students in veterinary schools has increased by 11%, according to the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC). The study also estimated that 80% of veterinary students are white.

At the CVM, starting with the class of 2018 and through the incoming class of 2024, the average percentage of underrepresented minority students in each class has been 25%.

Affordability has long been a factor in the makeup of veterinary classes, says Hanner, but for too long so has a status quo of limited visibility.

A Statement From the CVM on Diversity and Inclusion

We choose to be a culture that values diversity, inclusion, respect, empathy and equality for all.

Underrepresented minorities are far less likely to see veterinarians who look like them when they grow up, says Hanner. He says admissions committees often did not consider or see value in diverse DVM classes — diverse in not just in race and background, but in experiences, in ways of thought and different perspectives.

For too long, veterinary schools did not stress that a welcoming, supportive atmosphere was just as important to students as the quality of education, says Hanner. Sameness was ingrained.

“What I’ve always wanted to do was to be able to count underrepresented minorities in veterinary classes on more than just one hand,” says Hanner. “I hoped that there would always be enough that they wouldn’t have to worry about being a person of color, but just think of themselves as a member of a class.”

Hanner could have very easily just launched a veterinary career and left it at that. Instead, he committed to a career changing what veterinary medicine looks like.

In the past 15 years the number of underrepresented minority students in veterinary schools has increased by 11%. At the CVM, starting with the class of 2018 through the incoming class of 2024, the average percentage of underrepresented minority students in each class is 25%.

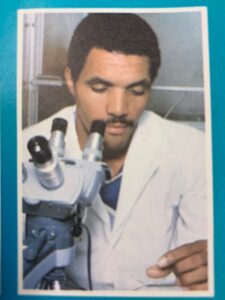

After graduation, encouraged by CVM veterinary toxicologist Cecil Brownie and by Webb, he joined North Carolina A&T as a clinical associate veterinarian in the laboratory animal science program and taught a diagnostic laboratory course. His career always included pushing for his students to consider veterinary medicine, inspiring them to feel undeterred by the color of their skin. He has organized and reviewed countless application materials with students, talked about classes that were needed and taken groups to visit veterinary campuses.

He has made veterinary school possible for so many and encouraged them to pass along the knowledge to make it possible for many more.

Hanner also changed the game at the CVM. As a past member of the admissions committee, he deftly encouraged others to consider applicants similar to those who may have previously been swept aside. He pushed for more people of color to join the college as professors and clinicians.

Since Hanner graduated from the CVM, there have been promising changes going beyond scholarship dollars. The average number of minority students in CVM classes has increased, especially in the past five years, and there is active recruitment.

Allen Cannedy, a close friend of Hanner’s, was named director of diversity and multicultural affairs at the CVM, and an Office of Diversity was launched, with faculty including Liara Gonzalez, Mathew Gerard, Isabel Gimeno and Marcelo Rodriguez-Puebla leading a diversity committee that has several student members.

Recently, safe spaces have been created for underrepresented minority students to receive support from minority faculty and staff. In 2018, the CVM was chosen to participate in a new admissions program designed by the AAVMC to encourage diversity.

“We practice inclusivity” is one of the four tenets of the CVM’s official values.

“Dr. Hanner is getting the acknowledgement and respect that he deserves for all that he has accomplished as a human being and as a member of our CVM community,” says Cannedy. “The scholarship speaks volumes for who Dr. Hanner is, what he stands for and what he has done for the college.”

A big part of Hanner’s legacy has been working with Cannedy and others to recruit students from A&T to come to NC State. A&T has long sent many of its pre-veterinary graduates to Tuskegee University, a private historically Black institution in Alabama with a prominent veterinary school (Cannedy is a Tuskegee alum).

A&T still sends many to Tuskegee to continue their education, but Hanner and Cannedy have worked for decades to reach out to A&T students about NC State, battling a perception that the college may not be the best fit for students and a history lacking outreach.

All I wanted to do was go through veterinary school and then start a career. But then that changes when you see there is an issue that is bigger than you but that you can do something about. — Tracy Hanner

Many students want to take advantage of attending an in-state school for veterinary medicine, especially one as highly regarded as NC State’s, but they want to know it’s a welcoming place, says Hanner and Cannedy.

“I think the biggest discouragement I witnessed was through admissions,” says Cannedy, who joined the CVM in 1995. “I just have listened and heard so many comments, thoughts, biases and prejudices that folks have displayed in the past, in how they thought about individuals, that they would not be successful in our program.

“It had been disheartening to see so many highly capable individuals not get a chance to come and do what they want to do. This has changed because it needed to change.”

Moving the Ladder

Less than a decade after Hanner graduated from the CVM, Shaka Monroe joined the class of 1997 as its only Black student and one of just a few students of color. When he visited A&T on his college search, he met Hanner, a veterinarian who looked like him.

That motivated him to enroll at A&T and join the school’s laboratory animal science program. He hoped to follow in Hanner’s footsteps.

When he interviewed with CVM admissions, the second interviewer was Syl Price, an African American veterinary oncologist. Seeing someone who looked like him in that moment assured him that he could do this, too.

“My impression from my interview onward was that this was a program that is inclusive and diverse,” says Monroe, now an emergency veterinarian in Pennsylvania. “I personally felt supported and was well-prepared for the challenges that came.”

Monroe found that support in many places. A best friend at A&T, Terry Keo, who immigrated from the United States from Cambodia as a child, joined the CVM class of 1998. As a child, Monroe delivered newspapers to Brownie’s home and now Brownie was one of his clinical instructors. Brownie, he says, took every opportunity he had to ask how Monroe’s studies were going and if he needed anything.

There were others. Monroe later met Cannedy during large animal rotations. Bruce Nwadike, an African American surgical resident, taught Monroe during his fourth year. Monroe said he also felt strong support from many non-minority instructors.

When he learned of the Hanner Scholarship, the class of 1997’s Shaka Monroe made a significant contribution, motivated by Hanner’s impact on his life and the CVM’s dedication to encouraging diversity in the veterinary field.

“My decision to contribute was a simple one; I saw that Dr. Hanner’s name was associated with a need that would benefit minority students,” says Monroe. “This scholarship could increase the numbers of minorities in the field, thereby enhancing diversity and providing more opportunities for minority children and students to see that if someone who looks like me can do this, then I can, too.”

Hanner was the first Black veterinarian Quincy Hawley ever met. This was in 2000 when he entered A&T.

“You know what I really remember the most? Just Dr. Hanner being there,” says Hawley. “He was always there for you. He was present. He listened and heard you.”

Hawley, a 2013 CVM graduate and now NCAMV president, was inspired to pursue veterinary medicine at NC State because of Hanner and Cannedy. Hawley was the first recipient of the Webb Scholarship. When he was a student, Hawley says he faced many of the biases Hanner encountered.

Hawley has entered an examination room wearing a white lab coat and stethoscope and has had people not believe he is a doctor, especially if he’s accompanied by non-veterinarians who are white.

“I imagine most veterinarians have never walked into a room before and had an owner tell them that they want another veterinarian because their dog doesn’t like Black people,” says Hawley

But, like Hanner, Hawley committed to being a voice for change at the CVM. He now serves on the college’s admissions committee, as Hanner once did. In the class of 2013, he was one of six students who were mentored by Hanner.

“If you care about diversity and inclusion, you will carry that with you everywhere,” says Hawley. “You will speak up when it’s time to speak up. You will think differently because it is needed. When you see someone you can support or inspire or help support the veterinary profession, you will do it.”

It’s not establishing an office of diversity or changing the college’s admissions approach or even the scholarship that bears his name that is Hanner’s strongest legacy. It is Hawley’s dedication. George Washington Carver inspired Webb, who inspired Hanner, who inspired Cannedy. They’ve all inspired Hawley.

They’ve also inspired Andrea Gentry-Apple. Hanner was also the first Black veterinarian Gentry-Apple met when she enrolled at A&T in 2007. The fact that she was meeting the first Black veterinarian to graduate from NC State, that such firsts were still so recent, was jaw-dropping, she says.

“Once you talk to Dr. Hanner, you can’t really forget him,” says Gentry-Apple. “Once you meet him, he sticks with you. He was a support system for so many. It wasn’t so much, ‘Oh, you can’t do that, you need to be doing this or you have to do that.’ He listened to you. He said, ‘All right, so what can we do to make what you want happen?’”

When Gentry-Apple joined the CVM class of 2015, it was the last group of 80 students before class size increased to 100. There were four Black women in the class, including her, said Gentry-Apple. The percentage of underrepresented minority students in her class was about 10%. Gentry-Apple particularly valued the support of faculty of color at the time, especially Cannedy and Ronald Baynes, a professor of pharmacology who is still a faculty member. But she yearned for more.

“Mostly the people who looked like me were staff, cleaning staff at that,” says Gentry-Apple. “And although you can definitely find allies in every shape, form and color, you’re still going to be drawn to African American faculty. It has definitely changed and continues to change. But do I think that we’re where we need to be yet? No.”

There is a lot of Hanner in Gentry-Apple. Both are bluntly honest but keep positivity close. And like Hanner, after graduation Gentry-Apple joined the faculty of A&T as an assistant professor of animal science. Hanner told her he had been a “ladder” for her. Now he told her she must be the same for others.

It’s Gentry-Apple who now mentors animal science majors at A&T, answers their questions about veterinary schools and tells them what NC State is like. She often visits the CVM and is encouraged by what she sees.

She looks at the student body and doesn’t have to strain to find that one minority student so common in past classes, she says. Several students she mentors at A&T become members of each new CVM class.

“It gives me comfort in the sense that they may not feel like they’re by themselves,” says Gentry-Apple. “They may not feel singled out. They may not feel like they are a black dot on a white sheet of paper.

“Seeing that makes me happier, knowing that I’m sending students who are succeeding and excelling in the program. They say we still have our issues, but it’s better and it keeps getting better.”

The Real Legacy

When Hanner is invited to speak at school he talks about the past, but he celebrates it.

He tells students about the legacy of Black veterinarians of color. He talks about Augustus Lushington, one of the first African Americans to earn a DVM in 1897. He shows pictures of Webb with her class at Tuskegee. He shows pictures of Brownie working at the CVM before his retirement in 2006.

He talks about David Brooks, a Lumbee Indian and Tuskegee graduate who has helped NC State and Tuskegee students earn scholarships. He talks about Lynn Hoban and Margie Lee, two African American women who both graduated from what is now the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in 1986, the same year Hanner graduated from the CVM.

“Progress is slow, but there has been great progress,” says Hanner. “It takes generation after generation to continue on and get us to where we want to be and where we should be. You see the potential in students like Shaka and Andrea and Quincy and you support them, hoping they will pass along the support.”

Hawley and Gentry-Apple were moved by how fast the scholarship was funded. Like Hanner, they call it a positive step but a stepping stone, an encouraging moment that shows people care about the principle the scholarship represents.

All three agree that more should and will be done to encourage inclusivity in veterinary medicine. Hawley and Gentry-Apple would love to deepen the impact of the scholarship, increasing the endowment to make it a full ride.

“I think there is more awareness of the issue when scholarships like this become a reality. I think the more leadership talks about it, the more talking about diversity becomes a comfortable conversation,” says Gentry-Apple. “One thing I think we really have to normalize is sitting down and having conversations about diversity and inclusion and not have anyone feeling prickly and feeling like they can’t talk or have an opinion or have a safe space.”

It’s difficult for Hanner to put into words how much the new scholarship means to him; he says it brings him to tears.

But what he’s most excited to talk about — what he mentions first — is that his classmate, Schopler, called him and talked to him about how he never completely understood Hanner’s daily struggles. That Schopler understands it in a way now, but knows he also can never fully understand it.

What Hanner wanted to talk about first was a story about a classmate who became his friend — and who still is.

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine

The Tracy Hanner DVM Scholarship Endowment By contributing to the Tracy Hanner scholarship, you invest in a strong culture of diversity and inclusion at the CVM and in veterinary medicine. To contribute, go here.