What I Learned “Fixing” the Dog: Second-Year Veterinary Student’s Experience in the OR

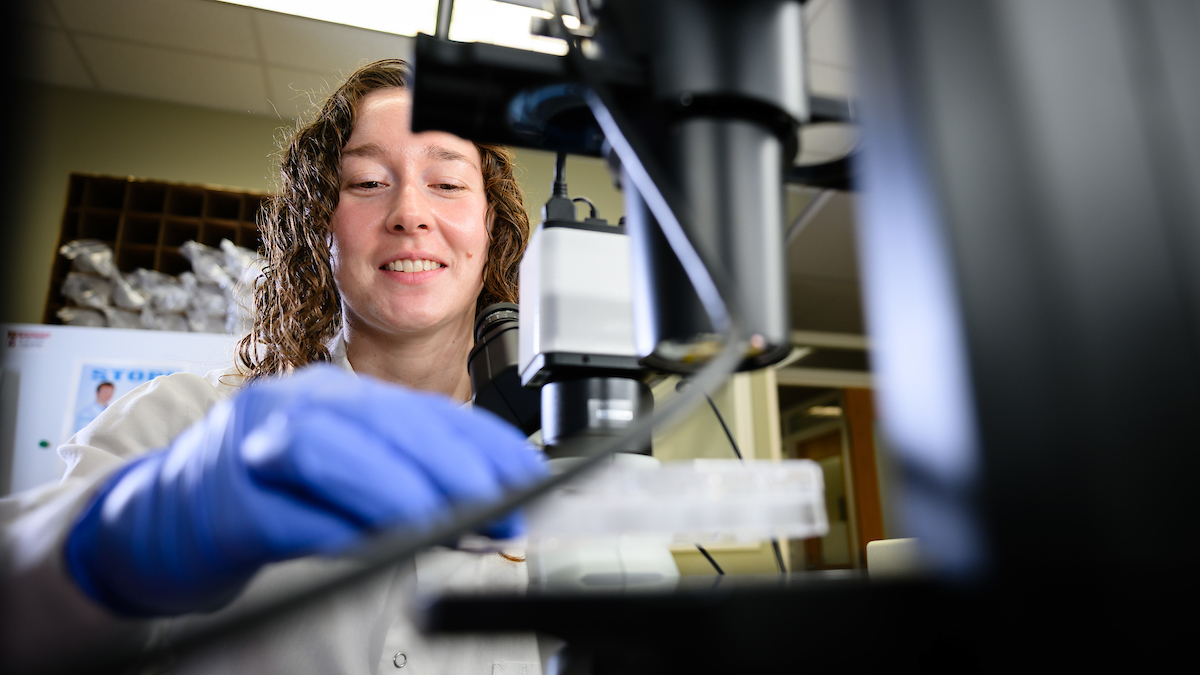

Surgery team members Sarah Blau (left) Daniel Carreno and Sarah Oxendine in post-procedure photo. Students learn spay and neuter procedures in the CVM Veterinary Health and Wellness Center.

Sarah Blau, a member of the Class of 2017 at NC State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, is sharing some of what she learns and experiences as a second-year veterinary student with readers of the CVM News Central Blog. Watch for these postings on a monthly basis.

Last month I picked up a sterile surgical blade for the very first time and made a delicate incision into the belly of a young female dog. My classmate and anesthetist for this surgery carefully monitored the patient’s vital signs at the head of the table. Another classmate, my surgical assistant, deftly blotted the cut area clean for me to proceed. I was so focused, my hands didn’t shake; not even a little. The goal: complete an ovariohistorectomy procedure, more commonly called spaying or “fixing” the dog.

Unlike my previous experience neutering a cat last spring, this procedure is much more invasive and requires the utmost care to maintain a sterile surgical environment. All second-year veterinary students at NC State University undergo this introduction to surgery. During surgery labs we learn how to dress in proper surgical attire and how to handle surgical instruments. We also learn suture patterns, practice hand-tying skills, and watch sample surgery videos over and over again to prepare for our big day, the day when we are wielding the scalpel.

This amazing second-year experience not only taught me essential surgical skills and provided my first sterile surgery experience but also encouraged me to think about why we do these (spay and neuter) surgeries in the first place. Like many, I grew up watching Bob Barker on “The Price Is Right” telling me to spay and neuter my pets to help control the dog and cat population that overcrowds animal shelters and leads to countless euthanasia procedures each year. For a long time, I though this was the only reason to “fix” a pet.

More recently I have learned of other advantages of spaying and neutering our pets. Spaying a young female dog before she first comes into heat reduces her chance of developing mammary cancer (similar to breast cancer in humans) by about 95 percent. This percentage decreases in proportion to the number of heat cycles the dog has had before being spayed. However, even in older females, spaying completely removes the threat of pyometra, a uterine infection that often becomes life-threatening and that about 24% of unspayed dogs will develop by age 10.

Similarly, neutering male dogs has shown to decrease the risk for developing certain prostatic diseases, although it seems to have no effect on the prevalence of prostatic cancer. Neutered male dogs are also less likely to roam away from home and to inappropriately urinate inside the house.

Unfortunately, having our pets fixed can have its down sides as well. Both male and female dogs that are neutered/spayed have a higher chance of becoming obese during their lifetimes. They are also at a higher risk of developing urine incontinence, meaning that they cannot always hold their pee and might leak urine. In fact, about 10% of spayed female dogs will develop incontinence – a fact I learned last year when my own three-year-old pup, Cheddar, started leaking urine in the house. This so-called “spay incontinence” can seem quite a hassle, but there are a couple veterinary drugs currently available that control the problem well.

Despite my own dog developing one of the most frustrating side effects from having been spayed, I would still recommend to almost anyone to have their pet fixed. I agree with many veterinarians that the advantages of spaying/neutering outweigh the disadvantages. The most important thing, in my opinion, is that pet owners know both the reasons for and against fixing their pet so they can make an informed decision.

Sometimes the decision is not up to the owner. Most animal shelters will automatically spay pets before they are adopted out. In fact, all the dogs my classmates and I spay this semester are from local animal shelters and rescues. In this case, it is even more important for pet owners to understand the benefits and risks associated with spay/neuter procedures that will already apply to their new adopted family member.

Now, as fall break draws to an end, I am eager for my next surgery, armed with my new skills and knowledge. I am also glad to have a better response to the question “why should I have my dog fixed” rather than just that Bob Barker said we should.