To Surveil and Protect: The Fight Against Antimicrobial Resistance

In the thick of war it pays to know your enemy, and bacteria is an unrelenting, captivating foe.

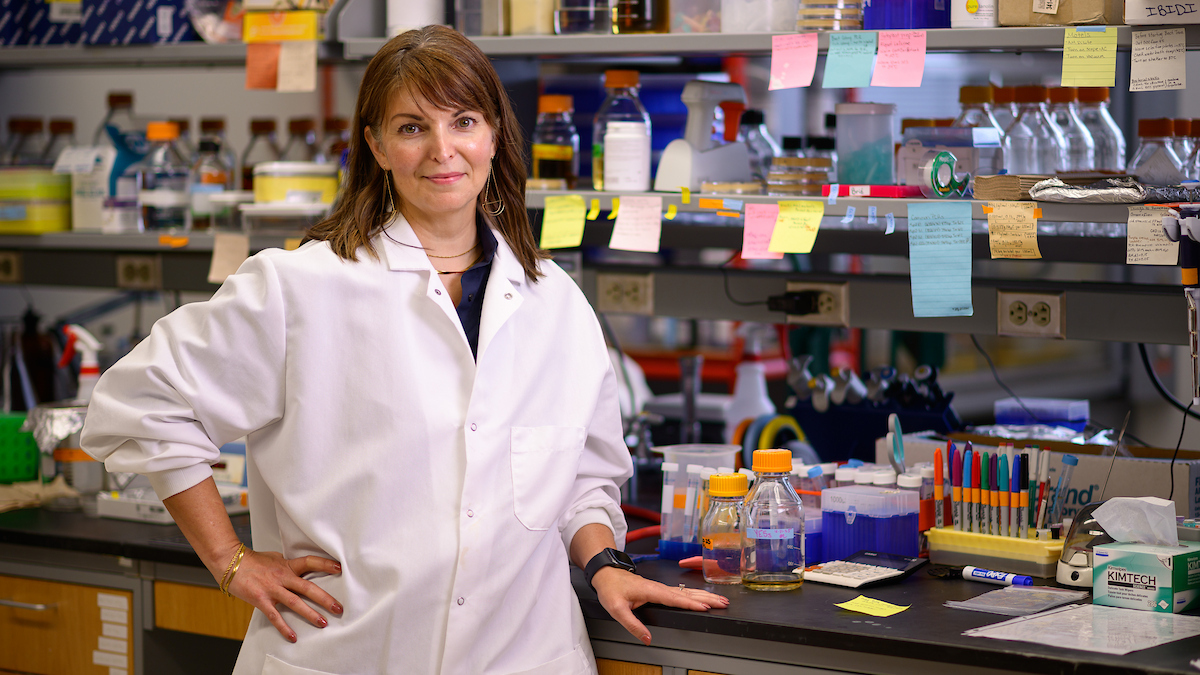

“How does something that you can’t see, that doesn’t have a brain, develop very sophisticated survival mechanisms almost immediately?” said Paula Cray, head of the department of population health and pathobiology at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. “You have to be in awe that something has been here since the beginning of time and has outsmarted the smartest of us.

“That is the grand challenge. How do you tame this beast?”

The challenge is combating a rising tide of drug-resistant bacterial pathogens, including strains of E. coli, Salmonella and campylobacter, some of the most common agents of foodborne illnesses.

It’s a global fight, and the CVM is an integral part of the armor.

“You have to be in awe that something has been here since the beginning of time and has outsmarted the smartest of us.” ~ Paula Cray

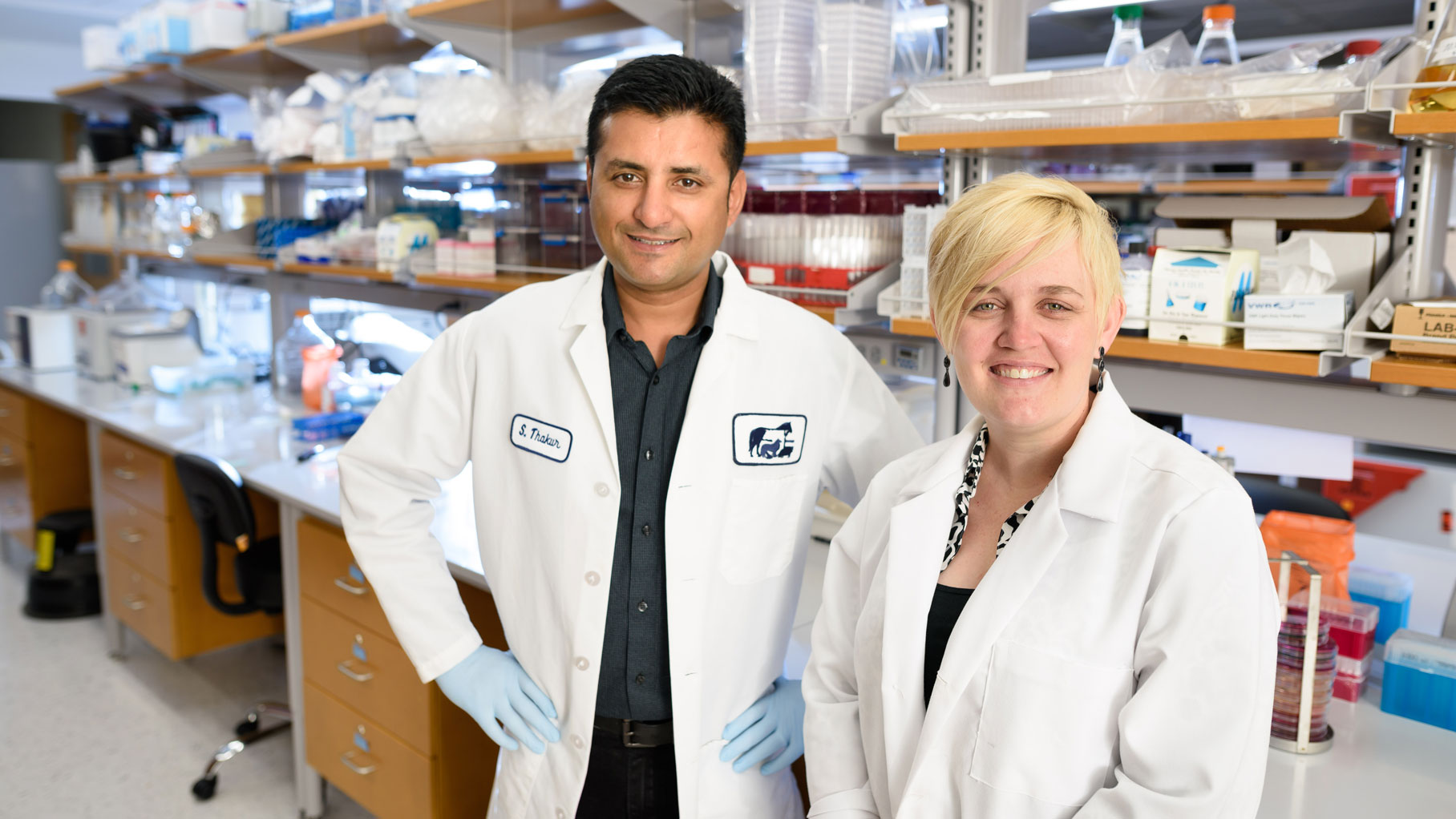

United States Food and Drug Administration recently awarded a grant to the CVM for a five-year study monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends in retail meat sold in the area. A research team of Cray, Siddhartha “Sid” Thakur and Megan Jacob will collect pork, chicken, ground turkey and ground beef samples from stores in North Carolina and from them generate complete genome sequences of Salmonella, E. coli, campylobacter and enterococcus to detect emerging antimicrobial-resistant strains. The work will be done with support from the North Carolina State Laboratory of Public Health.

The data will be added to the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System, or NARMS, used to identify dangerous strains and definitively pinpoint sources of outbreaks. NARMS was established in 1996 as a collaboration between the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The new grant means that North Carolina is now part of two national antimicrobial resistance surveillance systems — and both are in Thakur’s lab at the CVM.

Last year, Thakur’s lab also became part of the FDA’s GenomeTrakr program, a worldwide network of labs conducting whole genome sequencing to identify pathogens. Thakur, CVM associate professor of molecular epidemiology, recently received a grant giving long-term funding for GenomeTrakr at NC State.

“We’re providing powerful information,” said Thakur, who also leads the emerging and infectious disease research program at NC State’s Comparative Medicine Institute. “We are not just working in-house. We’re now an important part of determining the entire picture of antimicrobial resistance.”

A True Global Problem

Antimicrobial-resistant strains of bacteria in chicken and pork are common sources of foodborne illnesses. The Centers for Disease Control estimates 48 million Americans each year are sickened by contaminated food and drink, leading to 3,000 deaths. A 2013 CDC study found that 2 million people in the United States become infected with bacteria that’s resistant to antibiotics.

By participating in NARMS and GenomeTrakr, the CVM helps paint a portrait of antimicrobial resistance trends forming slowly but steadily. Isolating genomes and adding information to databases is painstaking work, but in antimicrobial resistance research, it’s vital.

“We go all the way from the farm to all the way down to the genome sequencing,” said Thakur. “That’s as deep as you can go. With drug resistance research right now, it’s all all about filling in gaps of information.”

New resistance mechanisms in bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses are emerging and spreading in increasing numbers. Resistance can happen through natural genetic changes, as well as through exposure to antimicrobials and antivirals in animals and humans. Mutations can be spontaneous or acquired. Some bacteria, like strains of enterococci, are particularly effective as reservoirs for antimicrobial resistance, easily acquiring it and then and sharing it with other organisms. E. coli behaves differently from Salmonella, which behaves differently than staphylococcus.

“From a pathogen perspective, it’s often survival of the fittest,” said Thakur. “When they are exposed to these different antibiotics, they usually die. But over a period of time, they adapt to make changes and survive eventually. They figure out that they need to maintain that change because, otherwise, this drug is going to kill me.”

Antimicrobial resistance research also plays a critical role in maintaining healthy food animal populations. Jacob, associate professor of microbiology and director of the CVM’s diagnostic laboratories, has long been dedicated to advancing techniques of diagnosing and monitoring antimicrobial-resistant organisms in animals such as feedlot cattle. Jacob often works on an array of research projects with Derek Foster, CVM assistant professor of ruminant health management, including better ways to monitor antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract of cattle. Foster’s unofficial antimicrobial resistance research team includes newly hired CVM faculty specializing in infectious disease and microbiomes.

There’s a reason why so many disciplines and institutions must work together to combat antimicrobial resistance. Drug resistance impacts livestock farmers in Africa and families in American suburbs. It does not discriminate between the young and old or the sick and the healthy. It impacts effective treatment of tuberculous, pneumonia, malaria and HIV, as antibiotics developed decades ago become less effective.

The World Health Organization says that antimicrobial resistance is “an increasingly serious threat to global public health.” Last fall, when WHO members held a two-day on conference on antimicrobial resistance, they did so at the CVM.

“In scientific communities it’s understood that someone’s headache is not just their headache. It can become my headache very soon.” ~ Sid Thakur

Cray has been part of an advisory group to WHO on antimicrobial resistance issues since it was founded 20 years ago.

“It’s work done for the societal good, not just human society but for the animal sector,” said Cray. “Surveillance systems provide the foundation for driving things forward. Being a part of a national program and doing global work puts us at the table for being informed and informing science.”

Within NARMS, the CDC heads data collection related to human disease outbreaks and the USDA participates in monitoring antimicrobial resistance in animals. The FDA’s retail meat research program bridges the gap between what’s going on at a farm and what’s put on the dinner table.

Everyday work at the CVM reflects that three-pronged surveillance approach. The CVM is also home to a portion of the Food Animal Drug Residue Avoidance Databank, to help prevent drug residue in animals humans eat. Students are exposed early and often to issues related to drug contamination and proper use of antimicrobials and help conduct research on effective antibiotic practices for both companion animals and farm animals.

“In the students I regularly see, every one of them has a passionate opinion on antimicrobial resistance because it affects every one of them to some extent,” said Jacob. “It affects the way they can help their patients.”

It affects researchers, too. Fighting antimicrobial resistance is like chasing something that’s always just out of reach. Everything that has been done to counteract or combat drug-resistant bacteria, Jacob said, bacteria have found a way around it all.

“By the time we find out how they change, they change again,” she said. It’s daunting, but it’s exciting. We have to find a way to do it faster and better.”

A Part of the Solution

Antimicrobial resistance impacts every country in the world, but every country doesn’t deal with it in the same way. That’s part of the problem.

“I think this is some of the most exciting work someone can have. It is the grand game. It is the game that has yet to be beat.” ~ Paula Cray

When Thakur was in India on a WHO grant studying antimicrobial resistance, he was able to walk into a pharmacy and get whatever type of drug he asked for. Sometimes, the same types of drugs are used for humans and animals in different countries. Regulations are not uniform and public health priorities vary from country to country.

“That’s the ground-level reality,” said Thakur. “The problem is then having new mechanisms of resistance emerge quickly in India, in China, in Southeast Asia. And these mechanisms can come the U.S. in a matter of 24 hours. Pathogens don`t worry about international physical boundaries”.

“In scientific communities it’s understood that someone’s headache is not just their headache. It can become my headache very soon.”

That’s why part of the five-year strategy for NARMS to is to expand the program outside of the United States, said Thakur, and for the past two decades, the surveillance network has steadily grown in both size and scope.

In 1997, NARMS launched its animal monitoring component, focusing on Salmonella testing and in 2011, NARMS data helped resolve a Salmonella outbreak passed through ground turkey. Just last year, the CDC awarded grants that allowed every state to sequence human isolates of Salmonella. Retail meat testing recently expanded to 18 states.

“The antimicrobial resistance data here at NC State is being accepted at a national and international level,” said Thakur. “The whole world is going to see it and see what’s happening in North Carolina.”

And even after 25 of years of researching antimicrobial resistance, Cray can still look into a microscope and not just be amazed but fiercely motivated to continue the battle, one bit of information at a time.

“It’s combating something that continually challenges you to think and think differently,” said Cray. “I think this is some of the most exciting work someone can have. It is the grand game. It is the game that has yet to be beat.”

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine