Saving Snakes from Spherical Snacks

Snakes are excellent predators – or maybe we should say “egg-cellent,” since eggs are often on the menu. But snakes’ senses can sometimes be fooled by other ovoid objects, like golf balls. And when a hungry snake can’t tell the difference between an egg and a golf ball, it can cause serious problems.

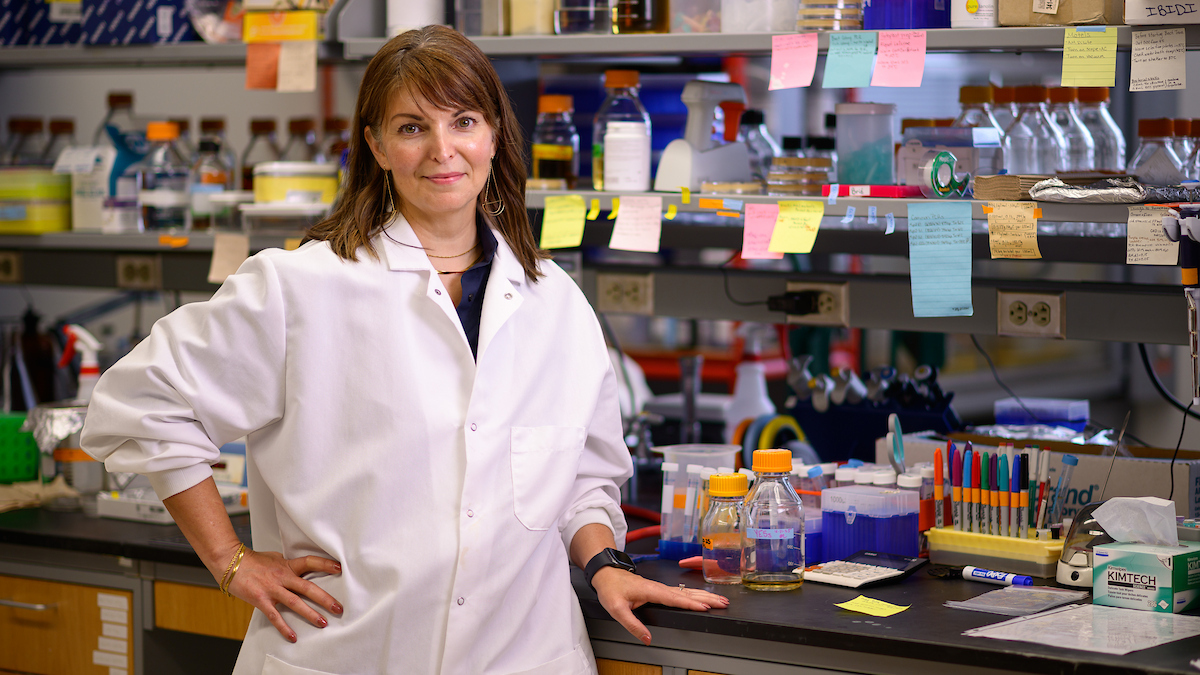

Greg Lewbart, a professor of aquatic, wildlife and zoological medicine at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, specializes in developing innovative treatments for our aquatic and reptilian friends. In a newly published study in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, Lewbart and his four co-authors described four case studies where non-surgical attempts were made to remove golf balls from the digestive tracts of snakes. The results were mixed.

The Abstract sat down with Lewbart to talk about what happens when a snake eats a golf ball, and whether a non-surgical approach to removal is recommended.

The Abstract: First of all, is swallowing golf balls common in snakes? Common enough to be considered a hazard?

The Abstract: First of all, is swallowing golf balls common in snakes? Common enough to be considered a hazard?

Lewbart: I think it is pretty common. I’m sure we only see the “tip of the iceberg,” as many (most) people would not bring us a snake in distress (versus a turtle, for example). Some people with chickens use golf balls as a deterrent and even as a method to kill egg/bird-eating snakes. It’s also likely that snakes near golf courses and driving ranges also consume golf balls.

TA: What happens to snakes that swallow these objects? Do they starve to death? Do they suffer internal injuries? Can these be passed naturally?

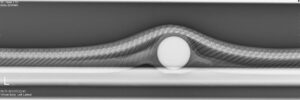

Lewbart: In my experience they will surely die without intervention. At least that’s the case for the snakes we see. I think the golf balls end up adhering to the inside of the gastrointestinal tract and then cannot go either way. They slowly starve to death.

TA: Are there complications from regular surgical removal that made trying non-surgical methods necessary, or is this work part of a generally non-invasive philosophy?

Lewbart: The latter. We have removed a handful of golf balls over the years via surgery without complication. It involves general anesthesia, expense, time and some risk. When co-author Brad Waffa was a student he brought up the idea of possibly using an endoscope for a less invasive approach. We did it and aside from a skin tear it worked. Years later alumnus Greg Scott (DVM ’12) had a couple of cases and hence a project was born. There are actually lay YouTube videos of the process. We think if the snake is found right away the golf balls can be more easily removed.

TA: Are non-surgical and endoscopic procedures more likely to be successful if performed earlier because the golf ball isn’t as far down?

Lewbart: Once objects get out of the stomach and into the intestines it almost always means surgery.

TA: Finally, if someone comes across a lumpy snake – how can you tell the difference between a well-fed snake that just ate an egg and a golf ball-eating snake in distress?

Lewbart: Good question. If they were willing to palpate the snake they would know it is not normal. The swellings are very discreet and firm.

Editor’s note: It should go without saying, but we do not recommend that untrained passers-by palpate nearby snakes – even if they are lumpy.

Tracey Peake/NC State News Services