Researcher Studies Effectiveness of Canine Pain Medication

By Kelley Weir for Morris Animal Foundation

Humans have been controlling their own pain for thousands of years—not so for animals. Just two decades ago, a graduating veterinarian would have completed relatively little course work that addressed pain management in pets because the standard thinking was that pain management could actually cause animals to injure themselves more. Thankfully, things have changed drastically over the years, and research has shown the importance of pain alleviation in the healing process. Veterinarians now have the knowledge and training to offer pet owners many options for treating pain in the furry and feathered friends who share their homes.

Pain management for animals has come a long way, and Morris Animal Foundation has become a leader in funding pain management studies for all animals. In the last two decades alone, the Foundation has increased its funding by 67 percent for studies that focus on pain management for animals. This increase was in line with an industry trend that began in the early 2000s, when pet owners and veterinarians began demanding more information and options.

Tuning in to pain type

What began as trying to manage pain in pets after injury or illness now includes preventive measures to reduce or avoid pain altogether. Dr. Mike Petty, president of the International Veterinary Academy of Pain Management, says, “Animals feel pain as much, if not more, than we do, yet due to survival instincts they try to hide their pain.”

There are two types of pain: acute and chronic. Acute pain is usually temporary and results from something specific, such as surgery, an injury or an infection. Chronic pain lasts beyond the term of an injury or painful stimulus, but it can also refer to cancer pain, pain from a chronic or degenerative disease and pain from an unidentified cause.

Dr. Petty points out that, regardless of whether pain is chronic or acute, animals tend to hide their symptoms. The goal of veterinarians—and pet parents—is to see through the facade. A position paper by the American College of Veterinary Anesthesiologists on treatment of pain in animals states that the prevention and alleviation of pain in animals is a central, guiding principle of practice. Those in the industry advocate that animal pain and suffering are clinically important conditions that affect an animal’s quality of life, and that methods to prevent and control pain must be tailored to the animal.

“The trend of pain prevention has resulted in research that is trying to validate both acute and chronic pain scales to better understand when animals are in pain,” Dr. Petty says. “There is also a big move for pharmaceutical organizations to develop specific pain medications or delivery systems so that we don’t have to rely on crossover from human medications.”

Morris Animal Foundation is doing its part to find solutions. For example, the Foundation is funding several studies that are establishing subjective pain scales for companion animals, some of which are described in this issue.

Dealing out the right dose

In addition, some Foundation-funded scientists are working to establish proper dosing or administration techniques for drugs that are already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in humans. These medications offer potential solutions to pain, but because drugs are metabolized differently in animals than in humans, the dosing must be appropriate.

“As veterinarians, we really need to know if these drugs work,” Dr. Petty says. “But without research, as we use these human drugs, we can go into uncharted territory.”

Not only do different species react differently to certain drugs, but individual animals also have unique reactions. Some pets respond positively to pain medications, called analgesics, while some don’t experience an effect or suffer negative side effects.

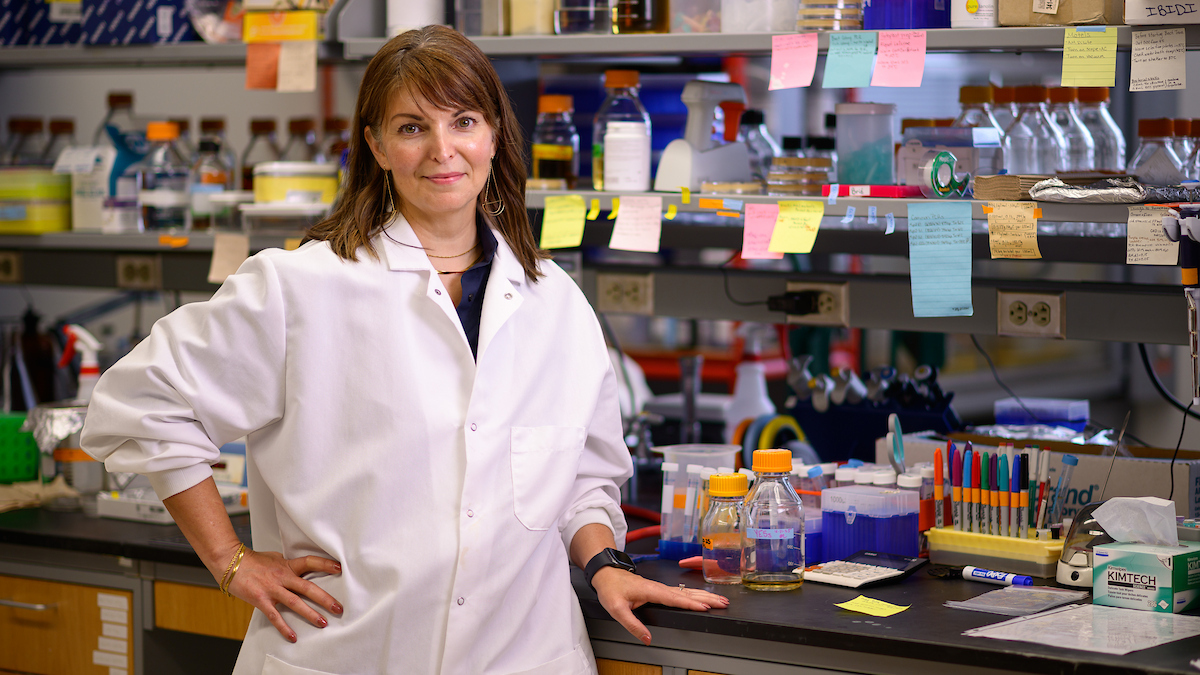

With funding from Morris Animal Foundation, Dr. Kristen Messenger, a veterinary anesthesiologist and researcher from North Carolina State University, is exploring reasons for these differences. She is looking at age, breed, sex, concurrent illness and how the drug carprofen is given to dogs, and she will then evaluate how these factors may contribute to diverse responses. Carprofen (trade name Rimadyl) is a commonly used pain medication for dogs. She will also look for alterations in plasma concentrations, or how the drug is absorbed, which may predispose a dog to develop adverse drug reactions.

While many studies analyze medications using healthy animals, Dr. Messenger’s study is unique in that she will monitor dogs that are already on the medication for preexisting conditions.

“This particular drug is the most commonly used drug at our veterinary teaching hospital, which shows how important this research will be,” Dr. Messenger says.

The research team will have the information and ability to perform genetic testing as part of future studies if important correlations are found.

“This study is the foundation for future research on the effectiveness of orally administered analgesics, such as carprofen, in dogs and should answer some important questions many veterinarians and owners have about this particular drug,” she says.

Pain management is not only good for pets but it benefits owners and veterinary practitioners as well. Patients enjoy improved quality of life, owners maintain the bond with their pets and veterinary teams experience improved morale and job satisfaction. When pain loses, everybody wins.

Updated Oct. 1, 2012