New NC State Veterinary Medicine Project Aims to Unlock Mysteries of Dog Pain

Deep down, pet owners know it. Veterinarians do, too.

There’s the bulldog who seems tougher than other breeds and the pug who’s a little more squeamish than others. There’s the golden retriever who is as happy-go-lucky as only golden retrievers can be, even when in pain.

What’s unknown is if there is actual science behind the perceptions.

A new study at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is hoping to be the first to answer an intriguing and potentially impactful question: Are there actual breed differences when it comes to pain sensitivity?

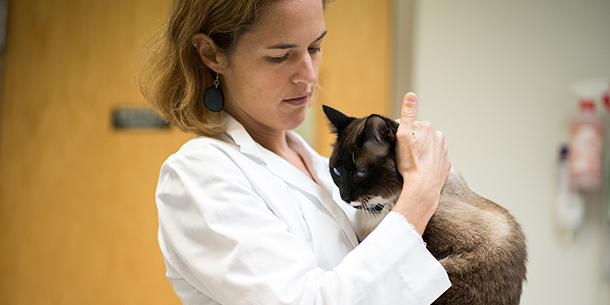

“We’re trying to pinpoint whether it’s just a stereotype that we carry around or if there is something to it,” says Margaret Gruen, CVM assistant professor of behavioral medicine, who is overseeing the research project. “If there is this biological basis for a difference in pain sensitivity, that would be something important for us to know from the standpoint of treatment of dogs, but also for understanding pain in pets.”

A Unique Look Into Pet Pain

The two-year study, funded by the American Kennel Club, is unlike anything done before at NC State — or in veterinary research.

For the past year, Gruen and her research team have recruited dogs from 10 different breeds — Chihuahuas, Malteses, Jack Russell terriers, Boston terriers, golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers, border collies, Siberian huskies, pitbulls and German shepherds — working with one dog a day to collect data.

A total of 180 dogs will participate in the study, and the team still needs additional Malteses and Siberian huskies to participate.

Dogs are examined to make sure they are in normal health and free from joint or other pain. They then undergo a sensitivity test, in which a small portion of hair is clipped from their front and back legs.

Three tools are used, two that apply pressure and one that applies light heat. As soon as the dog pulls away, the encounter is stopped. Researchers record the grams of pressure, or how long the dog tolerates the heat stimulus.

Each dog spends the rest of the afternoon in playtime, during which researchers assess a dog’s cognitive flexibility, as well as other characteristics such as attention span and emotional reactivity to new objects and a stranger — even their judgment bias, whether they are optimists or pessimists.

That information paints a well-rounded picture of what makes the dog tick and helps form an idea of whether some dog breeds are truly more sensitive to stimuli or more emotionally reactive in general.

The team begins analyzing data this summer. If it’s determined that certain dog breeds are actually more sensitive to pain than others, that would have massive ramifications. Dog owners may receive an even bigger picture of how their dog experiences and displays pain. Veterinarians could potentially tailor treatments to fit a breed’s unique pain sensitivity profile.

“The data are going to be fascinating regardless of what the answer is,” says Duncan Lascelles, CVM professor of translational pain research and the project’s co-investigator. “You can imagine the next step could be starting to look at the genetic makeup of these different breeds and relate that to pain sensitivity. And this has significant implications for breed-specific and individualized pain medicine in the future”.

If it’s determined there is no difference in breed sensitivity to pain, the question remains: How did such thoughts develop in the first place and how and why are they perpetuated among both dog owners and veterinarians? As a supplement to the research project, the team will also review nearly 2,000 ER records for a range of breeds.

“I think that’s my big motivator: What does this mean for when you bring a dog into the vet?” says researcher Rachel Park, a Ph.D. student at the CVM who is writing her dissertation on the study. “Are there certain assumptions that are already made before the dog gets in the door and then how do we as a veterinary community account for those?”

Attacking Pain

Preliminary findings are intriguing. Gruen was inspired to pursue the project after hearing a speaker discuss disparities in human medical treatment when she was a postdoctoral scholar at Duke University. That got her thinking about veterinary medicine and stereotypes of different dog breeds.

With Brian Hare, professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke, Gruen surveyed pet owners and veterinarians, asking them to rate pictures of 28 breeds of dogs on a pain scale from “not at all sensitive” to “most sensitive imaginable.” Then she asked them why they felt that way.

The results indicated that both groups felt strongly that different breeds of dogs did, in fact, differ in pain sensitivity. A dog’s size was the factor for the general public. For veterinarians, the “warmer” they felt about a breed, the less sensitive to pain they thought a dog was, which could indicate that they are forming an opinion on how easy the dog is to handle, says Gruen.

For the general public it was the opposite: The more warmly they felt about a breed, the higher they rated their pain sensitivity.

“We established that this phenomenon exists, but the question becomes, is it real?” says Gruen. “How would we test that and then does it matter? Does it impact the way we interact with dogs of different breeds? Does it impact the way we treat them, especially for pain?”

Just 10 years ago, no one was asking these questions. The study is believed to be the first to comprehensively break down pain sensitivity by dog breed. The study also represents a dream team of veterinary minds coming together to decode animal pain.

Gruen has been a part of groundbreaking studies into canine behavioral development, and Lascelles is one of the world’s preeminent scholars in the understanding and treatment of companion animal pain. In 2018, Laacelles co-founded the inaugural Pain in Animals Workshop, the first time veterinary and human medicine clinicians, government agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health, and animal health industry giants came together to discuss the best ways to measure and treat animal pain.

CVM postdoctoral scholar Rachael Cunningham, leading data collection, is a trained veterinarian; Park’s background is in animal welfare and psychology. Also contributing is Kenneth Royal, CVM associate professor of educational assessment and outcomes, who will help decode where the breed pain perceptions come from if they are not biologically based.

“Pain research in veterinary medicine has come a long way in the last 20 years,” says Lascelles, a board-certified small animal surgeon. “It has never had a ‘home’ of its own, like ‘surgery,’ or ‘cardiology,’ maybe because there’s not been an umbrella for it to live under.

“But now, it’s moved on to a position where people from several different disciplines are getting involved. I think this cross-discipline interest is fueled by the fact that there have been significant advances in our ability to measure pain and create treatments for it. Once you start to have some tools with which to perform your research, the speed picks up.”

A Breakthrough Approach

Studying pain in animals is challenging enough in itself: How can you accurately describe pain levels if the patient can’t verbalize it themselves? The solution is in the research team’s ingenious approach.

Park says it was tough at the beginning to recruit dogs for the study. On paper, pain sensitivity testing is a tough sell. However, researchers assured owners of the safety of the pain test and that if dogs felt uncomfortable or scared in any way, the study would be over.

They also emphasized the second part of the study — the cognitive testing session, the fun playtime and the free physical and orthopedic exams.

A big help: Park started featuring each participating dog on social media, humanizing the study experience. Because of pandemic restrictions, owners could watch the study live via an iPad from their car in a CVM parking lot.

“One thing that’s really important as a behaviorist is that you’re making sure that, yes, we’re doing research, but to have good quality data, dogs have to be comfortable,” says Park. “They have to be at ease; they have to enjoy the process. That’s just as important for owners to know, that we’re treating the dogs just like they would at home.”

Bonnie Giles knew a lot about her golden retriever, Eve, before participating in the study, but was curious to see how much of Eve’s personality was based on breeding versus breed. Eve came to the Giles home first as a foster in 2017 but became their permanent pet the same year.

“Eve is our party girl, our fear-of-missing-out girl, our girl that’s going with you as long as the adventure does not involve a vehicle,” says Giles. “She’s our optimist.”

The study confirmed Giles’ optimist assessment, but participating wasn’t just about confirming personality.

“The more data available regarding a breed’s strengths and weaknesses can help caregivers determine appropriate treatments,” says Giles.

Part of Cunningham’s role is talking to owners like Giles after the study is completed. When she applied for small animal surgery residencies last year, Cunningham also looked for opportunities to broaden her research experience. The CVM position offered her a chance to take a leading role on a project that could directly impact her future career as a surgeon.

“Pain management in veterinary patients is an important topic to me,” says Cunningham, who will begin a surgery internship at Michigan State University in July after data collection is complete for the first part of the project. “If we find that different dog breeds sense pain differently, that information can help veterinarians better individualize their pain management plans.

“If dogs don’t differ in their sensitivity, then veterinarians might need to reevaluate how they recognize and treat pain in breeds they think are ‘stoic’ or ‘overly sensitive.’”

And as the team prepares to analyze the results of the study for a year, Gruen is also excited for whatever comes next.

“I think that’s one of the things that’s so neat about this project,” she says. “Whichever way it goes, it’s going to be interesting and it will fuel new research. I think if we find a difference in sensitivity, then that will certainly lead to a lot of interesting avenues for pain research in veterinary medicine. I think if we find no difference, that’s still interesting for veterinary medicine.”

The research is also representative of where veterinary medicine is right now in pain research, says Lascelles.

“Pain research is pulling in people from very different backgrounds and very different experiences to produce a much more comprehensive, elegant and interesting approach to answering these questions,” he says. “It epitomizes what we do at NC State.”

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine

For more information, here’s a link to a short questionnaire for interested owners: https://ncsu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3yCIig0kLvgyWdn

Follow the research project on social media: https://www.instagram.com/cvmresearch