NC State Researchers Partner with USDA to Combat Deadly Virus Affecting Pigs Nationwide

By studying the role unclean vehicles might have in transmitting a swine coronavirus, researchers help boost North Carolina’s food animal industry and support federal agencies in fighting other devastating diseases.

In human medicine, the word “coronavirus” conjures images of masks, vaccines and nasal swabs. But in swine medicine, a different coronavirus causing gastrointestinal symptoms has plagued pig populations and stymied veterinarians for a decade.

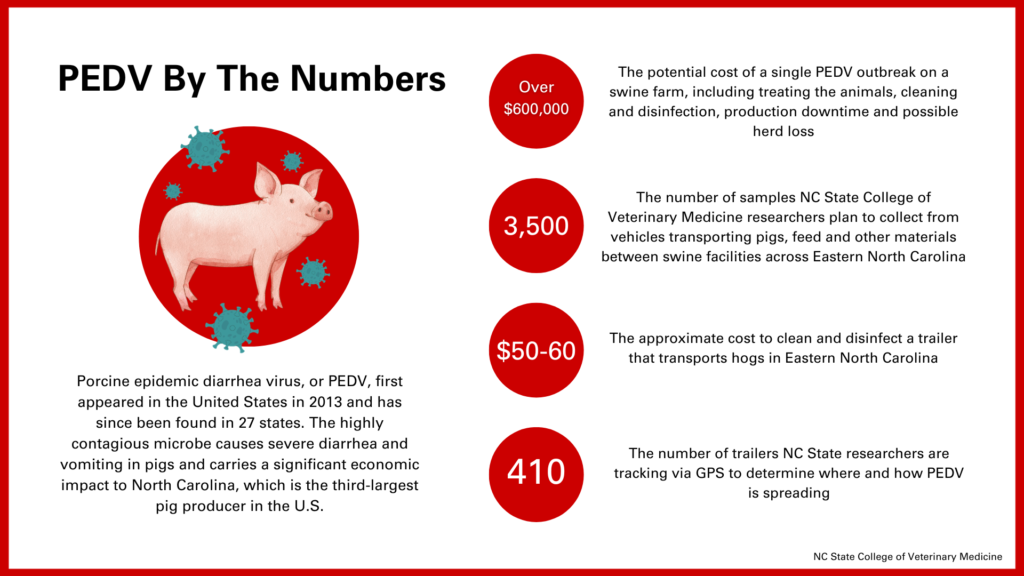

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, or PEDV, is a highly infectious microbe that causes severe diarrhea and vomiting in pigs. It has a mortality rate of between 50 and 100 percent in infected piglets but generally is not fatal in adult hogs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture notes.

A single outbreak can cost a swine farm upward of $600,000, NC State food animal epidemiologist Dr. Gustavo Machado says. As the third-largest pig producer in the U.S., North Carolina is all-too-familiar with the virus’ cost.

Now, supported by a nearly half-million-dollar grant from the USDA, NC State College of Veterinary Medicine researchers are launching the largest study of its kind focusing on a likely culprit of the virus’ spread: possibly contaminated vehicles.

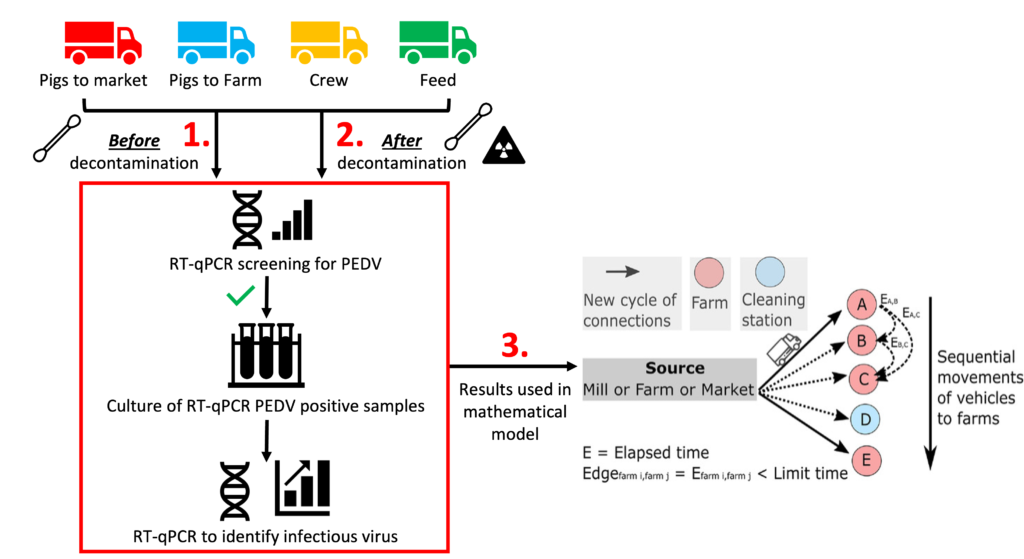

The NC State team will track vehicles hauling pigs, feed and other materials between swine facilities across Eastern North Carolina, swabbing the trucks and trailers at wash stations for evidence of the virus to assess how effectively these vehicles are being disinfected between stops.

“Veterinarians in North Carolina’s swine industry have identified PEDV as a major problem,” says Dr. Juliana Bonin Ferreira, the study’s primary investigator. “PEDV can be spread pretty easily and cause a lot of losses for state and national swine industries, because where we have pigs, we have PEDV. We are trying to help them identify a critical point of transmission and overcome and minimize that spread, which minimizes their economic losses.”

The team on the two-year study — Bonin Ferreira, Machado, forensic scientist Dr. Kelly Meiklejohn and virologists Dr. Barb Sherry and Dr. Michael Rahe, plus their labs’ staff — aims to recommend best practices for disinfecting vehicles between farms and provide an epidemiological model of how other porcine viruses could be transmitted between hog populations.

They were awarded the funding through a USDA program dedicated to preventing the spread of foreign animal diseases, like the extremely contagious African swine fever, in the United States. African swine fever, or ASF, has not yet been recorded domestically but is fatal and has no known treatment or vaccine.

“Essentially, if we can prove that the decontamination protocol of these vehicles is effective for PEDV, it’s likely going to be effective for ASF,” Bonin Ferreira says.

Between October 2023 and May 2024, when infections from the typically seasonal virus are at their peak, team members will swab various parts of the vehicles, including the animal trailer, the tires and the driver’s floorboard, before and after they are disinfected. The group will collect around 3,500 samples from 49 vehicles.

Meiklejohn’s lab will process the samples, looking for viral RNA signaling PEDV’s presence. This method is similar to how qPCR tests detect traces of COVID-19, Meiklejohn says.

But just as people with COVID can continue testing positive for the virus after they’re no longer contagious, these samples could test positive for PEDV that has stopped being infectious.

That’s where Sherry’s lab comes in: Her group looks for evidence of infectious virus in samples taken from PCR-positive vehicles to see whether the hog facilities’ disinfection procedures are removing the actual contagions.

Machado’s lab then combines that data with information from GPS trackers on 410 trailers paired with the vehicles to trace the origins of PEDV outbreaks and model where and how it is spreading.

As part of the study, researchers are also testing two different vehicle disinfectants in two concentrations each to determine which kills the virus most effectively.

Machado previously created an algorithm predicting where PEDV outbreaks would occur and tracked the role of vehicles in spreading swine diseases. He says the NC State team’s research is happening at a necessary time: The low price of pigs this year means farms will have fewer resources to combat viral epidemics.

“By working to reduce the infections of this disease, we’re not only impacting PEDV itself, we’re impacting the whole health of the herd,” Machado says. “We’re using PEDV as an example of a viral infection, but making our overall recommendations for disinfection will impact the whole health of all farms.”

The team’s researchers with backgrounds outside of swine medicine, Meiklejohn and Sherry, say the study demonstrates NC State’s commitment to cross-disciplinary research with wide-ranging impact.

“It’s exciting to get the opportunity to do research that could be benefitting not only veterinary medicine, but our key industry stakeholders here in North Carolina,” Meiklejohn says. “And it’s really great to have this federal funding and continue building our relationship with the USDA.”

Sherry, who heads the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, says she is grateful NC State recognizes the importance of collaborative research and enthusiastically supports it through its Integrative Sciences Initiative.

“This is where science is these days,” she says. “Team science is how we move things forward. I love the opportunity to be involved in something that has a very real application right now, and I’m learning every time I talk to my colleagues.”