NC State Researchers Create First Genetic Database of North Carolina Black Bears

Through genotyping, the interdisciplinary team provides the ‘bear’ necessities for officials to identify animals involved in law enforcement investigations and help manage wild black bear populations.

Using a broad DNA profiling panel for American black bears, researchers from NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine and College of Natural Resources have created the first genetic database for a subsample of North Carolina’s black bear population.

The database, which can be used to identify individual bears and localized groups, can help law enforcement and wildlife officials identify bears poached by hunters or involved in human-bear interactions reported to the state. Both uses are invaluable to officials in managing North Carolina’s black bears, which number over 20,000 statewide.

“Understanding the black bear population centers and how these populations are clustered on the landscape is an important benefit of UrsaPlex v2.0,” says Dr. Christopher DePerno, a professor of fisheries, wildlife and conservation biology in the College of Natural Resources, referring to the genetic identification panel used in the research. “There is also some real power in the forensics use.”

Researchers also discovered some allele variations unique to North Carolina black bears and different from those observed in the California black bears whose genetic information was used to develop UrsaPlex.

Furthermore, they detected genetic differences between black bear populations within North Carolina. The majority of the state’s black bears live either in the mountains or near the coast, and the variations detected between the western and eastern groups confirm they tend not to interbreed.

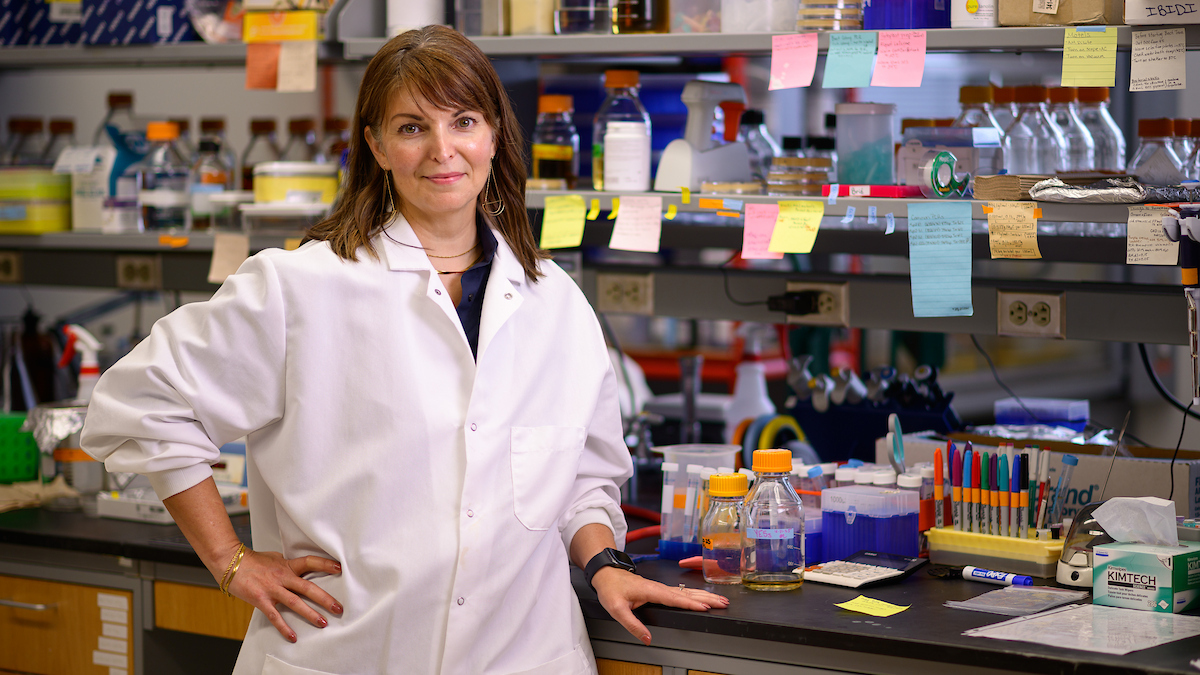

The research was funded in 2021 by a $10,000 intramural grant from the College of Veterinary Medicine, says Dr. Kelly Meiklejohn, an associate professor of forensic science whose lab processed and analyzed the samples used in the study.

Faculty from all three departments of the College of Veterinary Medicine contributed to the research: Meiklejohn from Population Health and Pathobiology, Dr. Michael Stoskopf from the Department of Clinical Sciences and Dr. Matthew Breen from Molecular Biomedical Sciences.

Fourth-year DVM student Samantha Badgett is the lead author of the study’s paper, published in Forensic Science International: Animals and Environments’ latest issue.

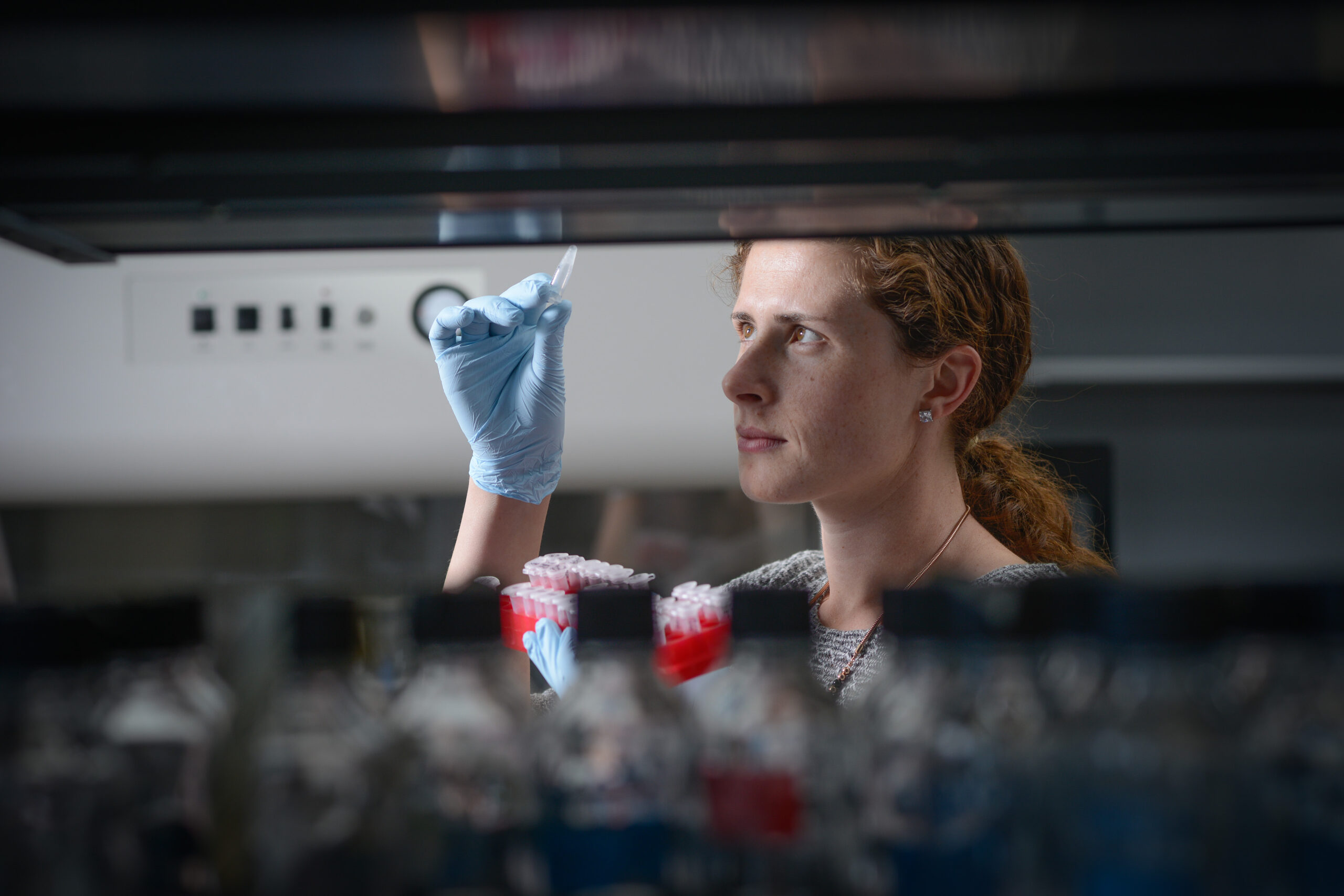

Badgett and Melissa Scheible, a research associate in Meiklejohn’s lab, isolated DNA from black bear blood, saliva and tissue samples to analyze with the UrsaPlex v2.0 panel, a series of steps that compiles a genetic profile.

The biological material was collected from a representative sample of over 350 black bears across North Carolina.

It included archived samples from previous CVM research studies and newer samples collected through DePerno’s decade-long study on black bears living in urban and suburban environments in Asheville.

Additional samples came from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, which approached Meiklejohn in late 2019 about compiling a black bear forensics resource and is a partner in the separate Urban/Suburban Black Bear Study.

UrsaPlex’s creators from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife gave support in running the panel and updating its second version.

Meiklejohn says the research would not have been possible without members of the interdisciplinary team contributing their unique resources and expertise.

“The project would have fallen in a heap if we could not access the samples from our collaborators,” she says. “There’s no way that my forensic biology research lab would have been able to get so many black bear samples from across NC ourselves. We are not an ecology or conservation laboratory and so are not equipped to go field sampling. We tapped into the resources that exist within the university and our partnerships.”

DePerno says collaborative studies are nothing new for his College of Natural Resources team, and it’s rewarding to continue advancing the field of wildlife genetics.

“When you’re working with a charismatic megafauna, everyone wants to be involved,” DePerno says. “And that’s good, because we can then ask landscape-level big questions, answer those questions and move science forward.”

A zoo-focused student, Badgett says the project tied together her passions for wildlife, research and forensics and drew from her previous experiences in chemistry, research and black bear rehabilitation.

“Honestly, it’s kind of a dream that this is my first publication, because it has pretty much all of my boxes checked for things I’m interested in,” Badgett says.

Badgett learned a lot from her lab work on the project, which included compiling, cataloging, extracting, amplifying, genotyping and analyzing the samples.

“It was really incredible,” Badgett says. “My co-authors and everyone at the Meiklejohn lab were just so welcoming and treated me as an equal partner from the very beginning. It was a little intimidating, because they’re all so intelligent and incredibly knowledgeable in their field, but I went from feeling like a newbie to learning so much in such a short period of time in a very niche area.”