NC State Researcher Tracks Cellular Mechanisms that Lead to Pulmonary Fibrosis

The following originally appeared in Results, a publication of NC State University’s Research, Innovation and Economic Development Program.

As a marathon runner, Dr. Phil Sannes knows the value of strong, healthy lungs.

As a professor in the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences in the College of Veterinary Medicine and a researcher with the Center for Comparative Medicine and Translational Research at NC State University, he knows the value of the scarred lung samples he obtained from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

The 60 tissue samples are part of a Recovery Act-funded project to study the cellular mechanisms that lead to pulmonary fibrosis. The disease, which afflicts five million people worldwide and is usually fatal, isn’t well understood by scientists.

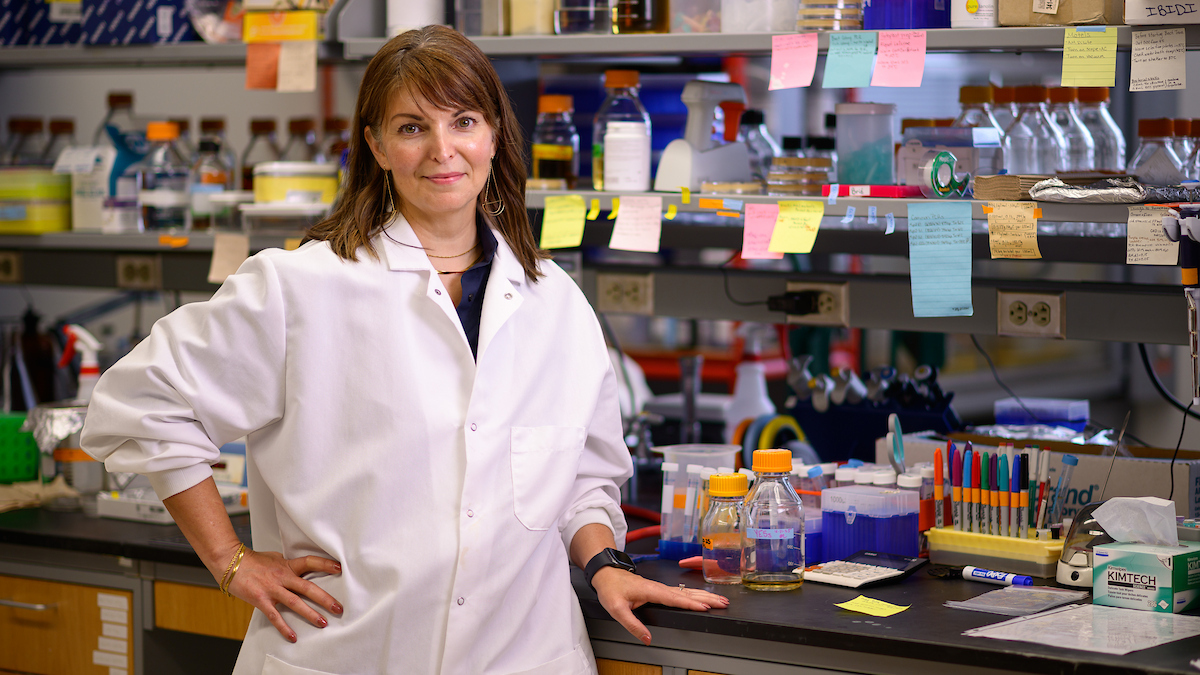

Dr. Phil Sannes is studying the genetic-signaling pathways in people who have pulmonary fibrosis.

Dr. Phil Sannes is studying the genetic-signaling pathways in people who have pulmonary fibrosis.Fibrosis develops when the epithelial cells that compose the ultra-thin lining deep inside the lungs die after being damaged by pollutants or infection and are replaced by fibrous tissue. Dr. Sannes says the process is a normal protective mechanism in the body to keep bacteria and other threats from taking hold inside the lungs. Usually, the fibrous scar gives way as new epithelial cells are formed. Sometimes, however, the epithelial cells never mount a comeback, and the fibrous tissue spreads like kudzu in an open field, overtaking healthy epithelial cells along the way. The thick, stiff scar then reduces the lung’s ability to deliver oxygen to blood cells. “The scales sometimes get tipped out of balance, and we go from normal repair to the body getting a signal that emergency medicine is needed,” he says. “We’re still trying to understand biologically what’s going on.”

Dr. Sannes has studied pulmonary fibrosis for more than two decades, examining the biology of the various types of cells in and around the lining of the lungs. He has discovered that a protein in the stem-like cells in the lungs that regenerate epithelial cells is not present in fibroblasts, the cells in the connective tissue that surrounds the lungs. Part of a group known to play a role in development and in cancer, this particular protein helps determine the path that genetic signals take within a cell, which could cause the cell to maintain a certain activity, divide or even die. The protein could be the driver behind different cellular responses and tissue repair outcomes, he adds.

The tissue samples from the NHLBI will help Dr. Sannes study the genetic signaling pathways in people who have pulmonary fibrosis. He has used the two-year, $149,000 Recovery Act grant to hire a research associate, who is studying two variations of the same pathway. One leads to normal functionality within the cell, while the other does not. “We have to solve this paradox of why cells that normally regress proliferate and cells that usually proliferate die.”

- Categories: