House Officer Highlight: Her Workplace is a Zoo — and an Exotic Animal Clinic and Several Aquariums

As an NC State zoological medicine resident, Dr. Lauren Mumm helps in healing thousands of exotic and aquatic animals across North Carolina while researching improvements for these creatures’ care.

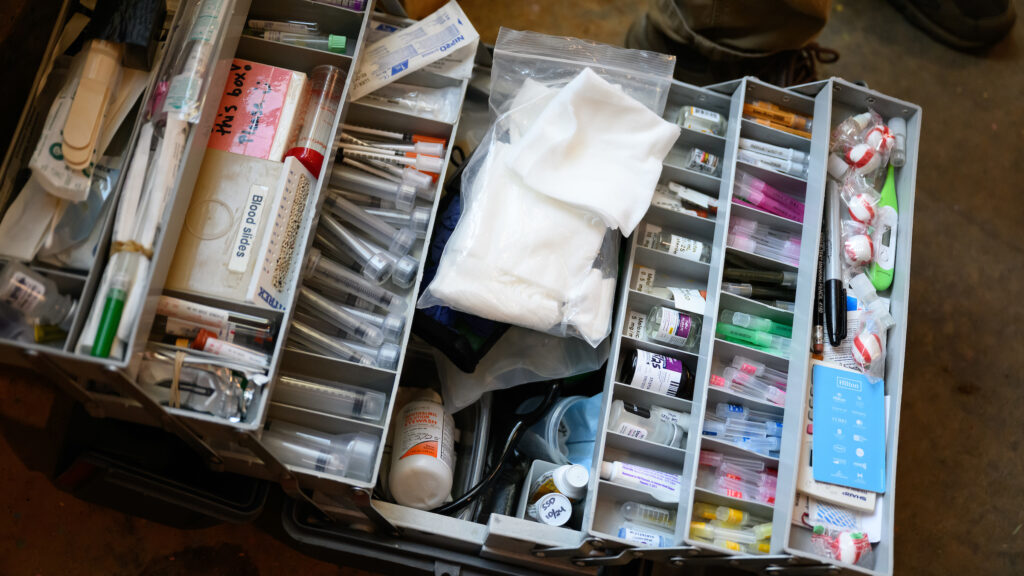

By lunchtime on a recent Friday, Dr. Lauren Mumm had already treated an African elephant’s foot abscess, performed a quarantine exam on a bongo antelope, given antibiotics to a spiny-tailed lizard and cleaned the shell of a river turtle with a fungal infection.

Though she is still a second-year resident at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, Mumm zipped around the North Carolina Zoo, the world’s largest natural habitat zoo, examining animals with the skill and panache of a seasoned attending veterinarian.

The zoo is just one of three campuses where the College of Veterinary Medicine’s three-year zoological medicine residency program is providing Mumm with firsthand experience in healing creatures across the animal kingdom, advancing veterinary research on their care and learning from veterinarians across our state.

The three-year program, designed to train veterinarians in all emphasis areas of the American College of Zoological Medicine, or ACZM, also rotates Mumm through the NC State Veterinary Hospital’s exotic animal medicine service, the NC State Center for Marine and Sciences and Technology in Morehead City and the three coastal locations of the North Carolina Aquariums.

“The hands-on component of any program is the most important for me, and this program really lets the residents have primary case responsibility,” Mumm says. “And that is the best way that I learn.”

The path to becoming a board-certified zoo veterinarian isn’t easy. To even qualify to take the ACZM’s board exam, veterinarians need at least three years of professional training after veterinary school and at minimum three published first-author research papers to their names.

But Mumm, who began pursuing veterinary medicine after she graduated college, has pursued this goal for a decade and grown only more enthusiastic about it as her experience builds.

“The two biggest goals for me [are] to come out of this program as a good zoo vet and to pass my board exam, and I do feel confident that I’ll be able to do both of those with this training,” she says.

From ice hockey to arctic animals

Before zoo medicine, Mumm’s passion was ice hockey, and it led her to the veterinary field in a roundabout way.

Mumm grew up playing the sport in Rogers, Minnesota, and attended the University of St. Thomas to play for the Tommies women’s hockey team. She entered the school as an art history major but changed her focus four times, ultimately majoring in biology because of her affinity for science.

She began volunteering at the nearby Como Park Zoo & Conservatory as an undergraduate and was hired on as a zookeeper after she graduated in 2014. There, she worked primarily with reptiles but also helped oversee the zoo’s bird yard.

“Working as a zookeeper is really what inspired me to want to be a zoo veterinarian,” says Mumm, who began veterinary school at the University of Illinois in 2016.

Mumm worked at a wildlife epidemiology lab while earning her DVM and spent two summers conducting field conservation biology research on Blanding’s turtles, a native and endangered species in Illinois.

After graduating in 2020, she completed a one-year rotating internship at Oradell Animal Hospital in Paramus, New Jersey, to add to her clinical skills foundation. From there, she matched into a zoological companion animal internship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“The path of least resistance to becoming an ACZM Diplomate is to do a residency and train with mentors who have that ACZM Diplomate status,” Mumm says. “In order to get into these competitive residencies, a majority of people do two internships beforehand.”

The ACZM recognizes just 22 institutions worldwide as having compliant training programs. When Mumm was applying to residencies, she made NC State’s a priority.

“This program has a very diverse clinical load, which I think is really important for not only being a clinical working zoo vet, but also preparing for the board exam,” Mumm says. “It also has a strong aquatic and invertebrate medicine component, and that is really unique in zoo residencies. And then we also receive strong mentorship for board studying from ACZM Diplomates who can help us through that process.”

‘An incredible asset to this program’

Mumm has no shortage of mentors through the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, from the clinical faculty on main campus to partner veterinarians at the zoo and aquariums.

“Dr. Mumm has always impressed me with her variety of skill sets,” says Dr. Sarah Ozawa, NC State assistant professor of exotic animal medicine and an ACZM Diplomate. “She is an excellent clinician, a caring colleague and an empathetic communicator. She has been a great advocate and peer to her fellow resident-mates and has provided great mentorship to the first-year residents this year. She is an incredible asset to this program.”

Mumm is also an accomplished researcher, Ozawa says. NC State requires zoological medicine residents to prepare five papers for publication by the end of their program, and Mumm has seven studies in progress as she wraps up her second year of residency.

One of these is a collaborative project with the NC Zoo evaluating the use of a viscoelastic coagulation monitor in chimpanzees. Her team is assessing how effectively the device can measure blood clotting in primates that have been sedated for routine procedures.

“That project has given me the opportunity to visit multiple different institutions outside of North Carolina and partake in chimpanzee anesthetized exams,” Mumm says. “And it’s been a really cool opportunity to see how these places all anesthetize these chimps differently for procedures and to get the opportunity to see things outside our program, too.”

In hockey, a “hat trick” refers to a player scoring three goals during a game. With three post-grad training experiences and three years at NC State working at three different locations, Mumm is completing a veterinary triple hat trick all her own.

“Between the clinical, research and mentorship opportunities I’ve had at NC State, I feel prepared to be a good zoo vet at any institution I end up with in the future,” she says. “I’m very thankful for this residency program. I’m very happy that I’m here.”

This article is part of a series featuring house officers across the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Hospital. Click here to find previous House Officer Highlight stories.