Her Dog Died of Lymphoma. Now NC State Summer Research Program Lets Her Work on a Cure

Kona, a peppy boxer with a big personality, was a ray of light for second-year vet student Meg Mulder when times got tough.

He could be mischievous but would sit patiently while Mulder performed mock physical exams on him, practicing what she’d learned working as a veterinary assistant.

But in January 2022, as Mulder was preparing to attend the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, 7-year-old Kona was diagnosed with late-stage lymphoma. He died the next month.

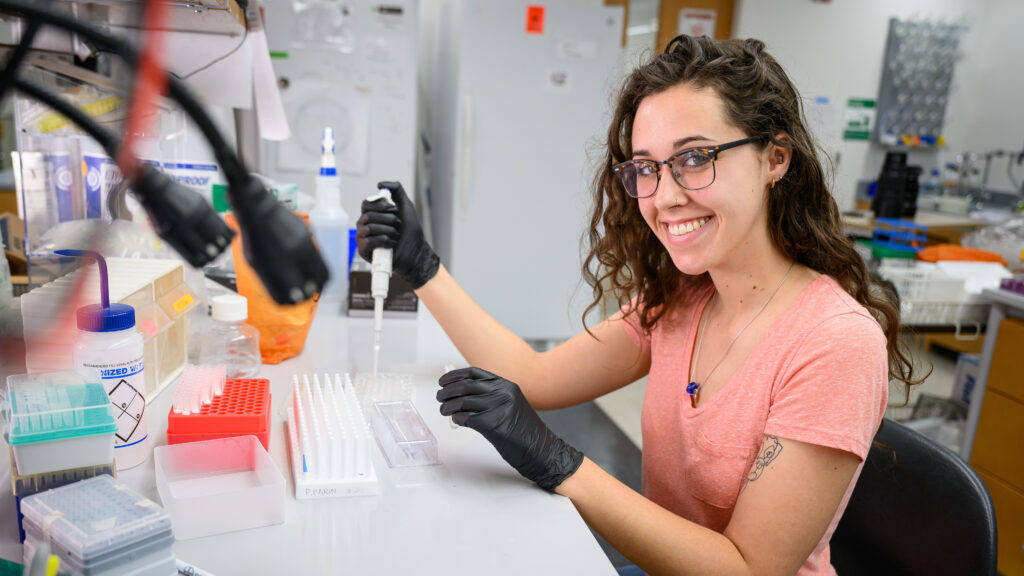

Now, Mulder is excited to be working this summer in a research lab on a potential vaccine treatment for canine lymphoma that could help other dogs recover. She’s one of 22 first- and second-year NC State veterinary students spending 10 weeks in faculty labs on mentored research projects as part of the college’s summer Veterinary Scholars Program.

“It’s rewarding to feel like I’m contributing even just a sliver of that knowledge to the world for dogs like Kona,” Mulder says.

For two decades, the program has given NC State students with little research experience the chance to work with faculty, graduate students and lab technicians while conducting research. The students also attend weekly seminars about the research process, learning how to apply for grants and present their findings, and get networking opportunities with local veterinarians working in outside research facilities. Participation also comes with a $6,500 stipend.

“It’s one of the jewels of the CVM in terms of teaching the veterinary students, but I’m a little biased because I’m a researcher and a veterinarian,” says Dr. Paul Hess, an associate professor of oncology and immunology who is serving as Mulder’s mentor. “The best thing about it is it takes people that are thinking about medicine a lot from a medical and clinical point of view and then essentially turns them into mini-scientists for the summer.”

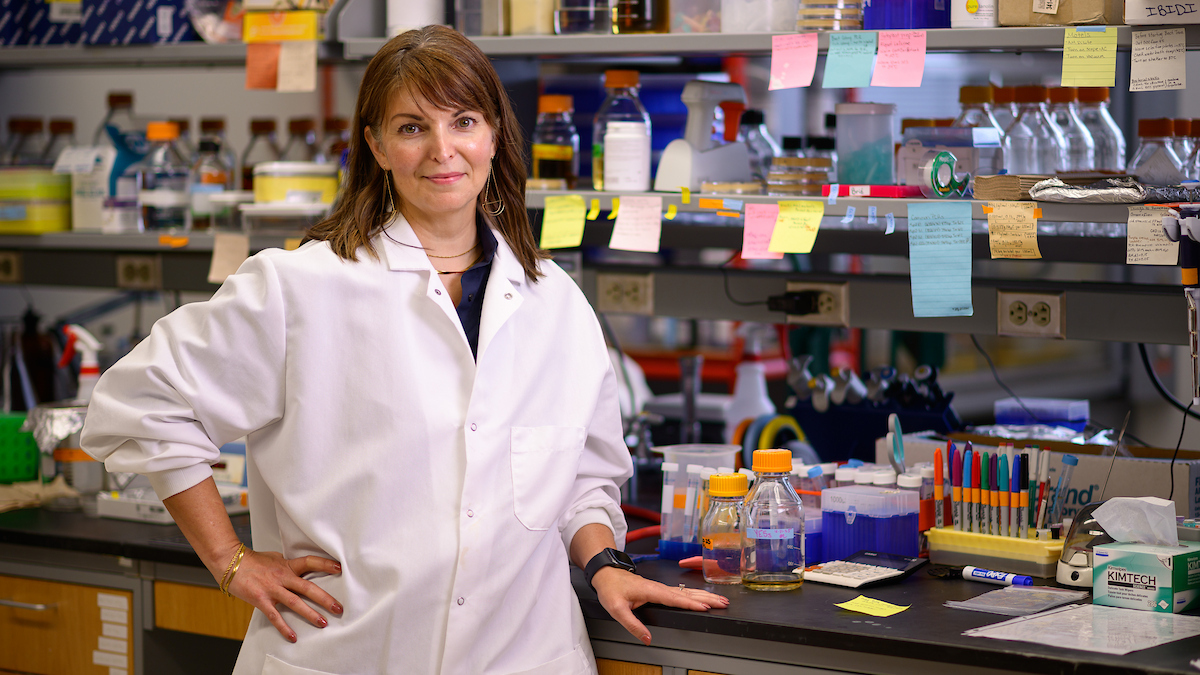

Before participating, many students understand how rewarding clinical work can be, but few realize the possibilities the lab holds for discoveries with profession-wide impact, says Dr. Jody Gookin, who co-directs the program with Dr. Sam Jones.

“There are different levels of gratification in those, and having students see that ladder of gratification can be very rewarding and life-altering for those students, career-changing for some,” says Gookin, the FluoroScience Distinguished Professor in Veterinary Scholars Research Education.

The offering is part of the national Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program. NC State’s program is one of the strongest in the nation and has been commended by the American Veterinary Medical Association as part of the college’s research curriculum, she says.

This year, students are researching subjects ranging from infectious diseases and pollutants in the Galápagos sea lion to the pharmacokinetics of oral antibiotics in steers.

Students will present their research at the Veterinary Scholars Symposium in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in early August. They will also share their abstracts with one another at a practice session at the College of Veterinary Medicine in July and exhibit their work at the school’s Research Forum on Aug. 11.

Mulder, who hopes to go into small and exotic animal medicine, says she was unsure about applying to the program because of her inexperience with research. Talking with Hess and learning more about the lymphoma lab gave her more confidence.

“I had never done research in this capacity before,” she says. “My previous research experience was all – thanks to COVID – virtual. So I’ve never really worked in a lab like this, and there’s just so much great mentorship, people to ask questions.”

Now, she is working to find new immunotherapy targets to treat the disease. Her research involves comparing cells from healthy and unhealthy lymph nodes and from the thymus, looking for specific genes that are only present in the lymphoma cells. Once detected, these genes could hopefully be used in a vaccine to prompt an immune response against the cancer cells.

Essentially, Mulder is checking the body’s filter to see if a treatment vaccine will work, Hess says, adding that no one has found these immune system “filter cells” in a dog before.

He says Mulder has grown as a researcher already. She is adept at troubleshooting problems and has made the project her own, mastering difficult technical skills in a short period.

“The critical step is getting these cells into a tube by themselves, and I think she’s made really good progress at doing this,” Hess says. “At the end of the program, I expect that we’ll probably have this new technique worked out in the lab, so she’ll have gained quite a bit, but we will, too.”

Mulder is glad she took the leap to intern, despite her initial concerns.

“Research was scary to think about doing for me,” she says. “But for one, I think it’s important to do things that scare you. And for two, it’s not as scary as I thought it’d be. I really feel like I’m learning a lot, growing a lot of skills, just expanding my knowledge base. I’d recommend it to anyone.”

And for three, Mulder is working in memory of Kona, whom she called her “heart dog,” or a canine soulmate that forms a once-in-a-lifetime bond with its owner.

“It does feel really cool to know that what I’m doing is directly impacting animals like the ones that I’ve loved,” says Mulder, noting that Kona will always influence her path through veterinary medicine. “I am super proud to be working for him and helping other dogs in his position to help advance their treatment options.”