NC State Student Publishes Groundbreaking Research on Eastern Box Turtle Anesthesia, Her Seventh First-Author Study

“Without a doubt, the highlight of my time in vet school has been my research experiences,” says fourth-year student Ashlyn Heniff, who faculty say already has an impressive portfolio.

The official state reptile of North Carolina, eastern box turtles are common patients at U.S. veterinary clinics as pets or injured wildlife.

Members of this species often need to be sedated or anesthetized for physical exams, diagnostic tests, and treatments because they tend to retreat into their shells and away from helping hands. Surprisingly, until recently no published research existed on the most effective ways to anesthetize eastern box turtles.

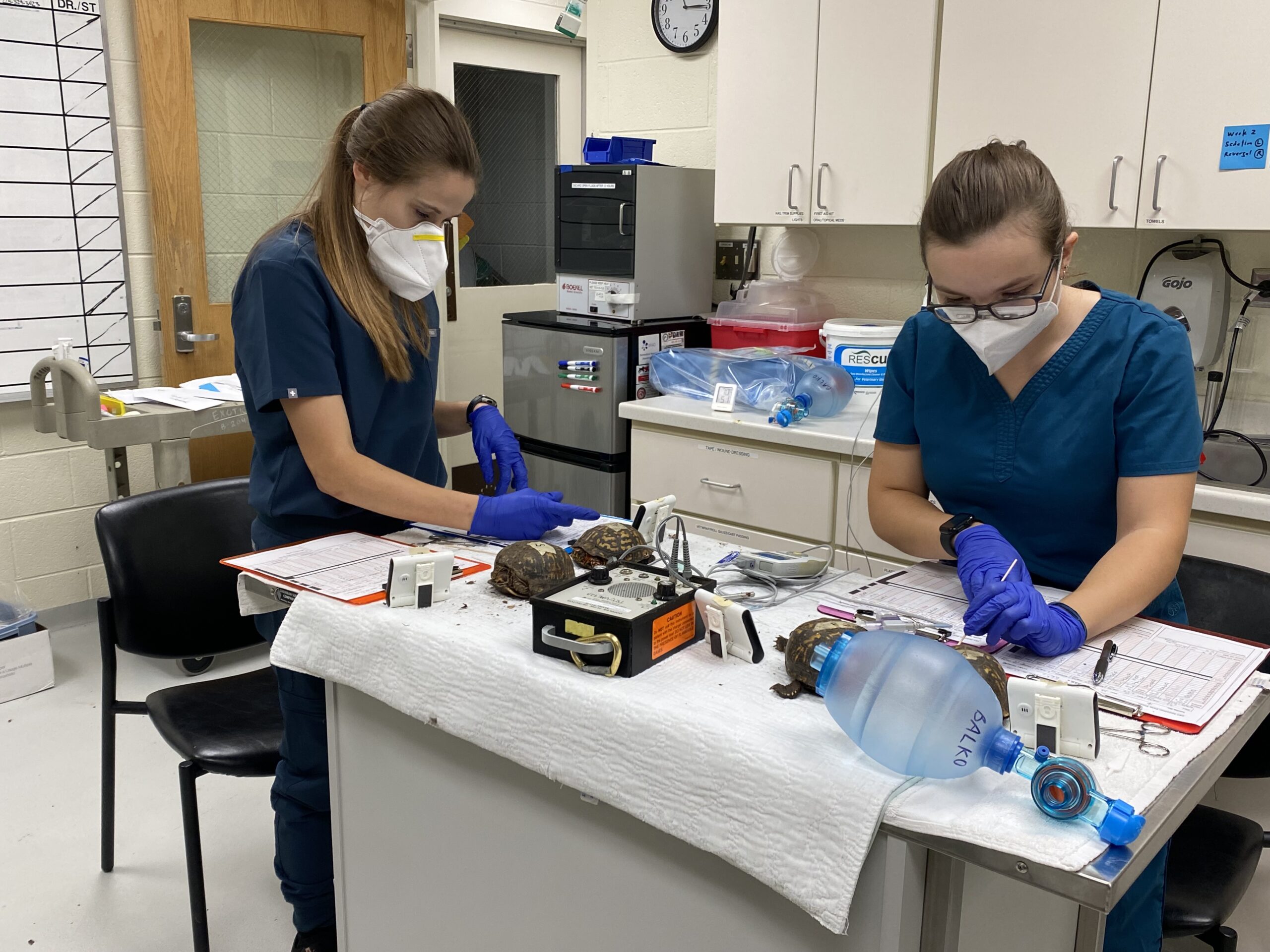

In December, an NC State College of Veterinary Medicine team led by fourth-year DVM student Ashlyn Heniff published the results of the first evidence-based study assessing sedation protocols in the species.

While evaluating how these reptiles’ bodies responded to different anesthesia administrations, the NC State researchers discovered a more effective drug combination and method to sedate eastern box turtles that will benefit veterinarians nationwide.

The research is a milestone for Heniff, too. The manuscript, published in the American Journal of Veterinary Research, is Heniff’s seventh first-author publication in under three years of research experience.

Heniff discovered a passion for research at the NC State CVM. Pursuing it has opened new opportunities for the zoo medicine-focused student, transformed her career aspirations and inspired her peers, Heniff and faculty say.

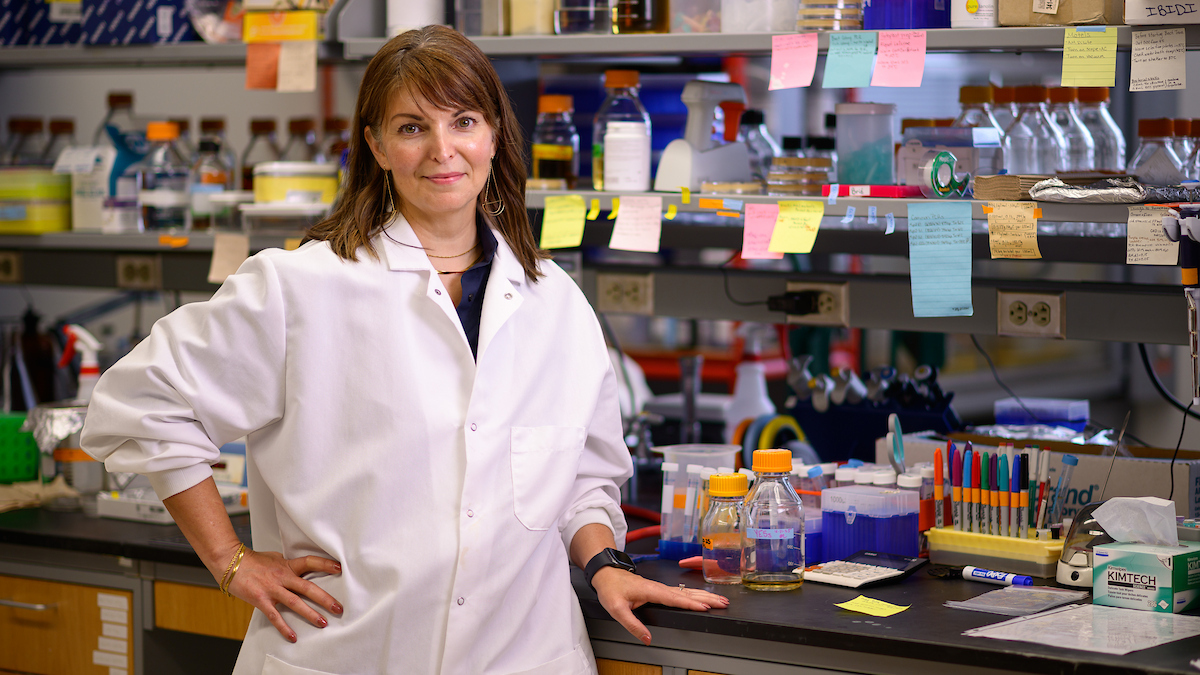

“I would estimate 10 to 20% or less of NC State veterinary students have one first-author publication, so Ashlyn is an outlier,” says Dr. Olivia Petritz, an associate professor of avian and exotic animal medicine who co-authored the study. “I think having that number of papers is even unique among our clinician scientist students. It’s impressive that Ashlyn is able to maintain such high academic scholarship and complete this additional, self-driven work.”

Heniff’s portfolio has come a long way in a short time, starting with an anesthesia study in thorny devil stick bugs during the summer after her first year. She cared for around 15 of what she called terrifying giant insects at her apartment before that initial project but says they did not scare her away from clinical research.

She has since studied more approachable species — including sea turtles, elephants, rhinos, various fish and, of course, box turtles — in experiences she says she could have gotten only at NC State.

“I specifically came to NC State from Indiana because I knew I wanted to do zoo medicine,” Heniff says. “And the opportunities I’ve had with research and mentorship here have been incredible. I am in a very good spot for where I always dreamed of being for my career, and a lot of that is because of this research and the people I’ve gotten to work with doing it. Without a doubt, the highlight of my time in vet school has been my research experiences.”

A ‘stepping-stone’ in sedation

The researchers’ eastern box turtle study yielded two takeaways.

First, injecting the sedatives, a dexmedetomidine-ketamine combination with and without midazolam, in the turtles’ forelimbs led to faster, more effective and less variable sedation than giving the drugs in the turtles’ hindlimbs.

Second, adding midazolam to the drug combination increased the efficacy of the forelimb anesthesia, making the turtles sedate enough for intubation in 89% of the trials.

The findings also suggest that eastern box turtles, like many other reptiles, process drugs through what’s known as a hepatic first-pass effect. This means that a drug given toward the reptile’s back end will often process directly through the liver before entering circulation, making drugs metabolized by the liver less effective and posing a potential risk for organ damage.

Heniff and Rachel Carpenter, another fourth-year DVM student, conducted the study with faculty advisors Petritz, Dr. Gregory Lewbart and Dr. Julie Balko.

The team’s research builds upon a previous Kansas State University study conducted in ornate box turtles.

Petritz says exotic animals are underrepresented in anesthesia research compared with more common companion animals like dogs and cats. Veterinarians who work with under-researched species are often forced to extrapolate drug administration protocols based on existing research in related species, and each new species-specific study provides empirical answers.

“Specific and published drug protocol data is incredibly helpful to safely sedate our patients and to discuss known risks and expected duration of the anesthesia to our clients,” she says. “Studies like these help standardize some of our clinical experience, and this will be yet another stepping-stone for other reptile sedation and anesthesia research to come.”

Co-author Carpenter is a former president of the NC State veterinary college’s Turtle Rescue Team. Eastern box turtles are the most common species the student team treats, she says.

“Our standard protocol is to use dexmed-ketamine and midazolam in the front limbs, so I was really excited and satisfied to see that these results showed more efficacy with that drug protocol,” Carpenter says. “Publishing research like this helps not only zoo practices but also wildlife rehab facilities, because we all need to know the best methods for our patients.”

Making research a priority

Even in the middle of applying for zoo medicine internships and starting her last semester of veterinary school, Heniff is still conducting research and doesn’t plan to pause anytime soon.

She recently had a paper accepted to the Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, the product of a collaborative study between NC State and the North Carolina Zoo to investigate viscoelastic coagulation technology that may aid in managing a deadly hemorrhagic disease in African elephants. She is also working on a project with another major zoo focusing on an endangered mammal species.

Wherever her post-grad career takes her, Heniff plans to continue clinical research.

“I would really like to work at a big-name zoo that has multiple veterinarians who can also dedicate a lot of time and energy to research,” she says. “I don’t want to be just a clinician, I don’t want to be just a researcher, I’d really like to work somewhere where I can do some of both — because I really, really like both.”

And though Heniff’s experience is an exceptional one, Petritz encourages all veterinary students to take advantage of the research opportunities NC State offers.

“Advancements in research are going to change the way these students practice medicine for the better, and knowing what these projects entail and how to critically evaluate their findings are incredibly important skills for veterinarians,” Petritz says.

May 10, 2024 Update: Heniff was named the recipient of an American Journal of Veterinary Medicine student award from her research with eastern box turtles.