NC State Gastroenterologist Awarded $3.5 Million NIH Grant to Improve Small Intestine Transplant Process

Intestinal transplants have a five-year success rate below 60%, but researchers say an emerging technology for pre-transplant organ storage could boost tissue health, improve patient outcomes and expand the donor pool.

For many people experiencing intestinal failure, a transplant can be life-changing but uncertain.

Over 40% of intestinal transplant grafts fail within five years, causing patients and their families to stress about future care. Researchers, including those at NC State, have identified that changing the way donor organs are stored and transported before surgery is one of the biggest opportunities to improve transplantation success rates and patient well-being.

Organs are traditionally preserved by refrigeration in a method known as static cold storage, but an emerging technology called normothermic machine perfusion, or NMP, has shown decreased rates of organ damage and increased rates of graft survival and function in heart, kidney and liver transplants.

Dr. Liara Gonzalez, an associate professor of gastroenterology and equine surgery at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, has helped pioneer research funded by the Department of Defense suggesting that NMP can also improve the success of intestinal grafts by preventing inflammation and promoting regeneration of damaged tissue before transplantation.

Supported by a $3.5 million R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health, Gonzalez is now launching a five-year study testing NMP’s potential clinical use in small intestine transplantation using a porcine model.

Her NC State lab and co-investigators from Duke University aim to demonstrate that the technology reduces instances of ischemia-reperfusion injury, or organ damage caused by the resumption of blood flow and oxygen, compared with the cold storage method, keeping these organs healthier long-term.

Gonzalez hopes her team’s work with NMP can expand the pool of healthy, transplantable organs and offer a lifeline to people with intestinal failure. Many of these patients are young children who would otherwise be dependent upon intravenous nutrition, she says.

“Studies show that patients’ qualities of life are dramatically improved when they have successful intestinal transplantation,” Gonzalez says. “I’ve always wanted to make a difference, and in doing this translational research, my team and I are able to make a greater difference and improve the lives of both human and veterinary patients with intestinal disease.”

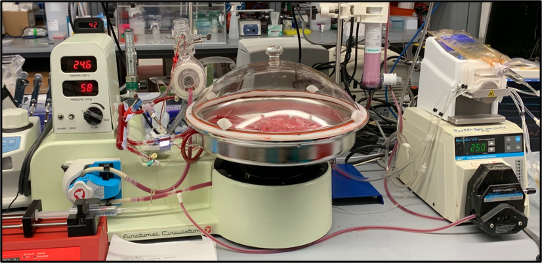

Normothermic machines essentially treat organs as if they were still within the body, Gonzalez says. They supply organs with nutrients, antibiotics and blood kept near body temperature and measure the tissues’ oxygen, pH and electrolyte levels.

Previous research shows putting organs in static cold storage for over six hours can damage the organs’ epithelial cell lining and their cellular barriers. Long periods of static cold storage are also linked to complications including recipient post-reperfusion tissue injury, the spread of disease-causing gut bacteria within the body and even transplant failure.

Gonzalez’s prior study showed that not only did NMP successfully store porcine small intestine over that time, but it also showed evidence of healing sensitive intestinal tissue from damage typically sustained in the organ procurement process.

But six hours is a very short time to package, transport and prepare an organ for transplant, Gonzalez says. The first part of her new study will test how long NMP can keep porcine intestinal tissue viable, with the goal of quadrupling the successful storage time to 24 hours.

“We’ll be doing a lot of different analyses, from gross observation down to stem cell culture, to evaluate the viability of the intestinal stem cells in the tissue,” Gonzalez says.

Once researchers identify the most practical storage period, they will transplant cold-stored and NMP-sustained small intestines into different recipients. An immunologist will compare any differences in the intestines’ immunological responses, including inflammation and changes in epithelial cells’ barrier function.

Lastly, the team will test the normothermic machine’s ability to repair injured small intestines for transplantation. Researchers hope this step will provide further evidence that NMP can broaden the available supply of transplant-ready organs.

“Right now, how clinicians assess a donor and their suitability is based on very broad parameters, but that decreases the pool of potential donors,” Gonzalez says. “In previous liver transplant studies, researchers have shown they were able to rescue some livers that would have otherwise been discarded using NMP and successfully transplant those.”

The R01 is the largest and most prestigious grant the NIH awards to a single principal investigator, but Gonzalez emphasizes her research is a team effort that has depended on the contributions of colleagues, lab leaders, technicians and trainees.

“A lot of times the principal investigators get the recognition, but the reality is that there were so many graduate students and technicians involved and we could not have gotten here without their dedication,” she says. “What has made this research successful is a group of can-do people who kept working toward our ultimate goal of improving the lives of people with intestinal failure.”

At NC State, Gonzalez’s current lab members include research specialist John Freund, equine emergency surgeon Dr. Elsa Ludwig and NIH Postdoctoral Fellow and Ph.D. candidate Dr. Caroline McKinney.

These talented scientists help NC State’s research span from barn to bedside, Gonzalez says.

“Given the resources we have here at the College of Veterinary Medicine and our proximity to human hospitals and medical schools, we’re in a very unique position to make significant advances in translational research,” Gonzalez says.

Gonzalez would also like to recognize the current and former contributions of the following NC State faculty and students to this research: Post-doctoral research fellow Dr. Elizabeth Goya Jorge; DVM/Ph.D. student Lydia Poisson; assistant research professor Dr. Amy Stewart; graduate alumni Dr. Cecilia Schaaf and Dr. Brittany Veerasammy; anatomical pathologist and associate professor Dr. Jennifer Luff; porcine immunologist Dr. Tobias Kaeser; flow cytometrist Dr. David Rose; and proteomics researcher and associate professor Dr. Manuel Kleiner.

She also extends her gratitude to Duke University transplant surgeons Dr. Debra Sudan and Dr. Andrew Barbas, along with surgical resident Dr. Nader Abraham, for their collaboration.