Global Health Program Awards First Research Grant

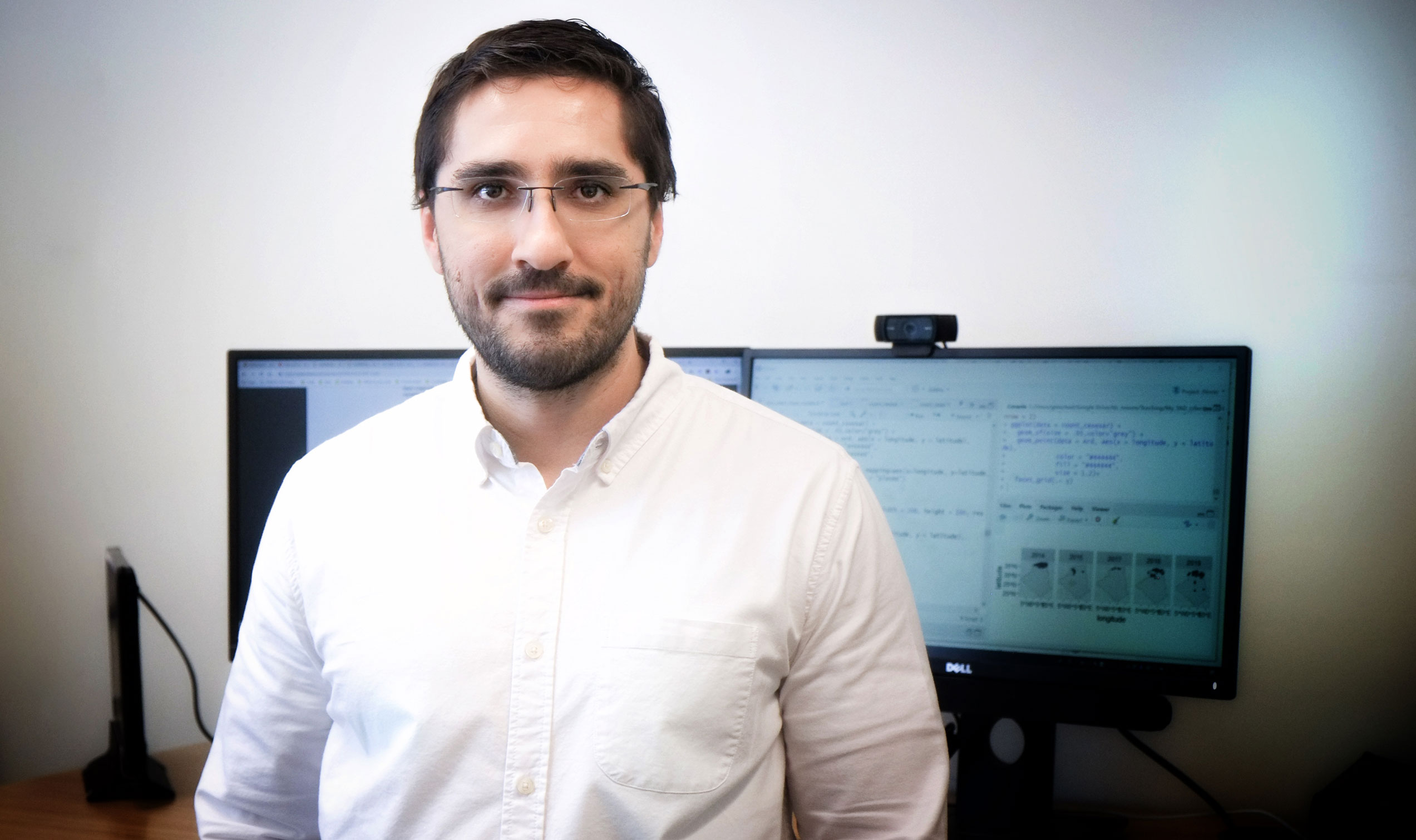

The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine’s global health program is awarding its first seed grant to Gustavo Machado, an assistant professor in the Department of Population Health and Pathobiology, for a project tracking the spread of infectious disease in Brazil.

The $20,000 award supports Machado as he maps swine trade routes in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s southernmost state. Machado and his collaborators in Brazil will track the spread of swine viruses between farms, helping contain future disease outbreaks and continue disease surveillance.

“We want to create mathematical models of swine trading so we can identify the areas that are at high risk for future virus outbreaks,” said Machado.

Machado will study the Seneca Valley virus, which circulates in pigs, with his co-investigator Cristina Lanzas, CVM associate professor of infectious disease, and her Ph.D. student, Trevor Farthing.

Although viruses like Seneca Valley may travel by air or contaminated animal feed and farming equipment, as much as 60% of diseases stemming from such viruses are caused by transporting infected animals to an uninfected farm, said Machado.

Originally from Brazil, Machado is an epidemiologist specializing in transboundary animal diseases, highly contagious infectious diseases that sweep through countries and across national borders. Machado’s research focuses on diseases harmful or fatal to livestock, which disrupt the economy, food security and livelihoods.

Each year, according to Brazilian veterinary authorities, about 26 million pigs are traded within Rio Grande do Sul. Seneca Valley virus does not appear to affect humans, but the virus causes lesions on the feet, snout and mouth of pigs.

To limit the damage caused by Seneca Valley virus, the research team will trace trade routes between farms and municipalities, and construct maps of trading communities throughout the state. The maps will be used to test computer-generated scenarios of Seneca Valley virus outbreaks, critical for pinpointing ways to quarantine the virus when outbreaks happen.

“We need to establish accurate analytical methods and a workforce to prepare for virus outbreaks, so that when we identify an outbreak, we have a better idea about which trade routes need to be halted,” said Machado.

To improve long-term virus monitoring in the country, Machado and his CVM co-investigators will also host a five-day workshop to train 15 veterinarians from Brazil on the project’s analytical approach, which includes network analysis and mapping techniques.

To develop the workshop, Machado is working with Andrew Stringer, CVM clinical assistant professor and director of global health education.

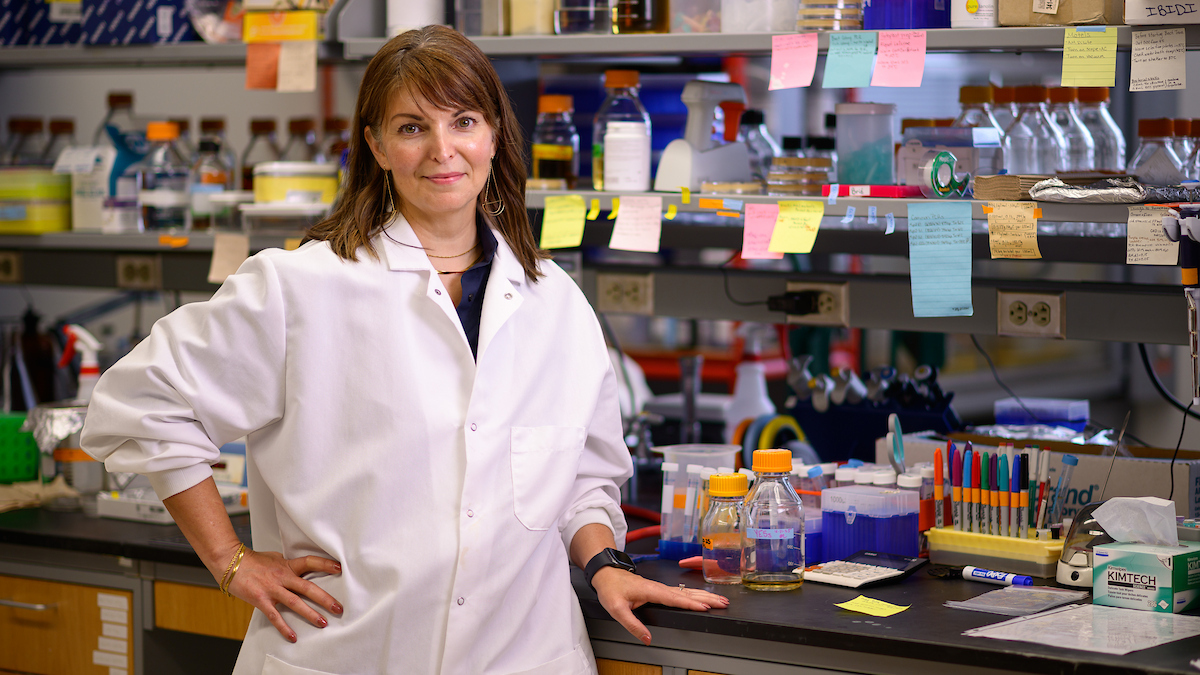

He is also working with Maria Correa, CVM professor of epidemiology, public health and policy, who has worked extensively in Latin America in disease risk assessment and communication.

“This is a great opportunity to combine global health research with specialized training to ensure a country has the independent capacity to protect their own people and economy,” said Sid Thakur, director of global health at the CVM.

Seneca Valley Virus: A Unique Research Opportunity

Seneca Valley virus belongs to a group of diseases that also includes foot-and-mouth disease. But unlike foot-and-mouth disease, Seneca Valley virus is a relatively new discovery, and not currently controlled by vaccinations. This represents a unique opportunity for global health researchers.

From a veterinary point of view, Seneca Valley virus is not an urgent threat; many symptoms are mild, and rarely cause livestock deaths. By contrast, foot-and-mouth disease is a significant global problem, causing major economic losses by reducing the productivity of livestock and restricting animal trading. Many countries, including the United States, have invested heavily in eradicating foot-and-mouth disease, but the disease still circulates worldwide.

The Seneca Valley virus and foot-and-mouth disease have very similar symptoms, said Machado, and by studying the Seneca Valley virus, researchers can gain important information on foot-and-mouth disease, and how to approach future outbreaks.

“This gives us an opportunity to study how Seneca Valley virus is spreading, which we don’t know much about,” said Machado. “But it also allows us to see what could happen if foot-and-mouth disease returned to a disease-free region.”

Livestock disease outbreaks have economic ramifications in the United States. In 2015, a lack information about animal movement in Minnesota led to an outbreak of avian influenza in turkeys, which quickly spread to 21 states and caused economic losses of $950 million. As the nation’s second leading producer of pigs, raising approximately 9 million pigs a year, North Carolina is also at risk from livestock disease outbreaks.

“Our work in Rio Grande do Sul could help places like North Carolina, because we’re all threatened by the same diseases,” says Machado. “We can use similar techniques to create networks of swine trading in regions like North Carolina, and identify which areas are most at risk from future outbreaks.”

~Greer Arthur/NC State Veterinary Medicine Global Health