Clinical Trials, Explained: How You and Your Pet Can Help Save Lives and Advance Veterinary Medicine

Participating in a veterinary clinical trial allows pet owners access to cutting-edge treatments that improve the standards of care for all types of diseases. Here’s how that process works at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine.

When Deidre Bruce took her newly adopted cat Punky to his first couple veterinary appointments in 2021, the last thing she expected to learn was that 1-year-old Punky had a progressive and incurable heart condition.

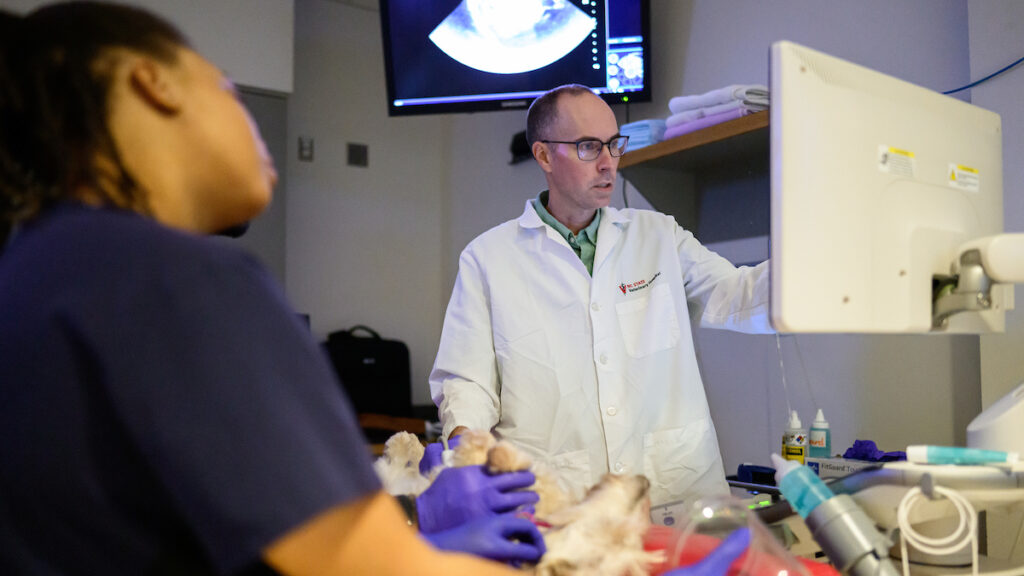

Punky was diagnosed with feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition that causes thickening of the heart’s walls and can eventually lead to life-threatening blood clots, congestive heart failure and sudden death.

The news left Bruce, an NC State College of Veterinary Medicine staff member, reeling. But soon after the diagnosis, Punky’s cardiologist offered a ray of hope: NC State veterinarians were running a clinical trial on a new medication to treat feline HCM, and Punky was an ideal candidate.

“I said, ‘Of course.’ There was no hesitation,” says Bruce. She enrolled Punky in the study that day.

Clinical trials provide an opportunity for health care providers and consenting patients to test a new medication or therapy for disease treatment or prevention within a carefully monitored environment. This vital, and often life-saving, research depends on the voluntary collaboration of community members who donate their time to advance medical progress.

Much like their counterparts in human medicine, clinical trials in veterinary medicine are carefully reviewed for safety by panels of clinicians and patient advocates long before the first volunteers can sign up. At the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, clinical trials have led to groundbreaking discoveries that have improved both animal and human health.

“Clinical trials put NC State at the cutting edge of research and innovation,” says Dr. Joshua Stern, associate dean of research and graduate studies at the veterinary college. “They offer a pathway to define new treatments and change the outcomes of disease, keeping our patients happier and healthier. In many cases, our clinical trials represent the first access to therapies that go forward to redefine the standard of care in veterinary medicine.”

The NC State clinical trial that Punky participated in was critical to making rapamycin, the first drug found to successfully treat feline HCM, available to cats nationwide. After Stern’s team conducted extensive research, including several rounds of clinical trials, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration conditionally approved the drug in March.

“I’m so eager to have the drug come to market so we can get Punky on it,” says Bruce. “We helped in its development in our own way. If owners like me don’t enroll our pets in clinical trials, then NC State wouldn’t be able to conduct this research to help other pets.”

How Do Clinical Trials Work at NC State?

The College of Veterinary Medicine’s Clinical Studies Core team organizes and oversees clinical trials that happen across the NC State Veterinary Hospital. Led by Research Core Director Brianna Johnson, the group regularly updates its list of active trials on the college’s website.

There’s a perpetual need for canine and feline volunteers in studies investigating topics from soft tissue sarcoma to chronic kidney disease to cognition. Opportunities for equine, exotic and farm animal volunteers occasionally arise, too.

For most clinical trials, pets should already have been diagnosed with the condition being investigated. Healthy pets can sometimes get involved to provide a control group for studies. Johnson encourages interested pet owners to check the college’s website and Facebook page to find trials and check recruitment guidelines.

“Clinical trials often offer novel treatments, and some people are interested in the fact that the treatment is something they cannot go to their regular vet and receive,” Johnson says. “People often don’t have insurance for their pets, and they appreciate that clinical trials offer care resources they may not have access to otherwise.”

Some people reach out just because they want to contribute to medical knowledge.

“I’ve heard perspectives like, ‘My pet has this disease and I lost a human relative to the same condition, and I want to do whatever I can,’” Johnson says.

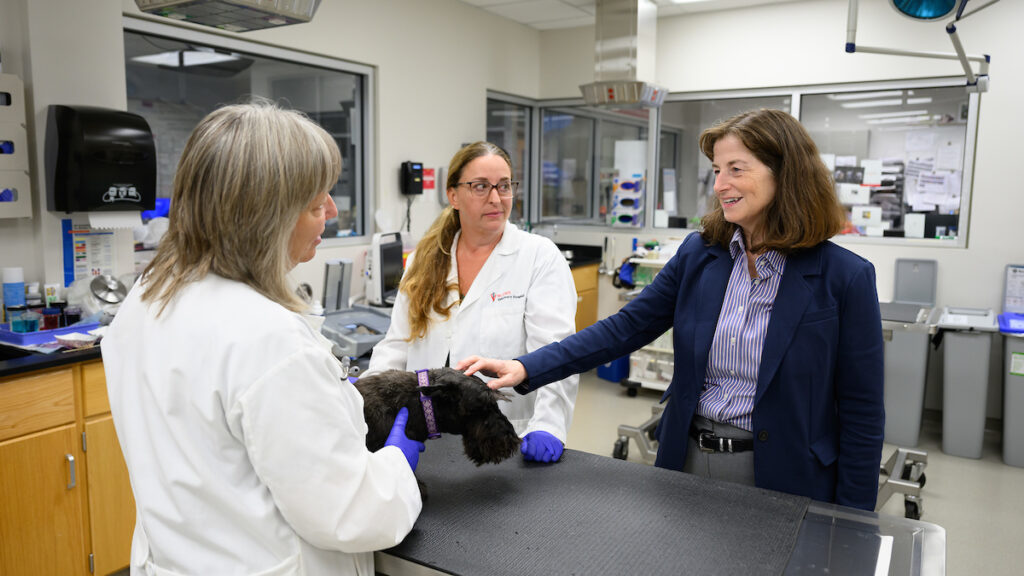

Participation in clinical trials is free, but what care is covered can vary from study to study. Once owners contact the trial’s coordinators, a member of the Clinical Studies Core team — likely research specialists Briana Diquez or Michelle Forte — will reach out with details.

Before pets can participate, the clinical studies group evaluates their medical records for eligibility. If an animal is a good fit, the coordinator will set up a screening appointment with the study’s primary veterinarian at NC State. This appointment provides the opportunity for the owner to meet the clinician in charge of the trial and sign a client consent form.

If a pet is selected for study participation, the Clinical Studies Core works with the owner to coordinate appointments. The length and amount of owner involvement vary study to study, Johnson says, and her team is a key resource for pet owners during that process.

“That’s why we’re here: to really provide that relationship with the client,” she says. “We take care of the extra communication, coordinate paperwork and relay appointment reminders.”

Owner participation is especially crucial at this point. Pet parents become scientists from the comfort of their homes, often administering medications on a particular schedule and monitoring a pet’s health. For example, Bruce visited NC State with Punky three times over a six-month trial period and maintained a daily log of his medication regimen and behavior at home.

“I think there’s this sort of ‘citizen scientist’ mentality where people like to participate in helping other pets and their owners,” Johnson says.

Once a pet’s participation in a trial concludes, it can still take awhile for the results of a trial to be released. That timeline depends on when trial participation numbers are met, if the treatment being studied is a medication seeking clinical authorization and many other factors, Johnson says. Owners can contact the research team with questions even after their participation ends.

“We always have the pets’ best interests at heart,” Johnson says. “We’re all striving to find these cures and develop new methods to help the animals we love.”

‘It’s a win for me’

To say Barbara Willen loves Scottish terriers is an understatement. She adopted her first dogs of the breed in 1969 and has raised and shown generations of Scotties since.

Her deep knowledge of Scottish terriers includes an understanding of the breed’s susceptibility to certain genetic diseases. She has enrolled her own dogs in clinical trials since at least the 1980s, both to keep her own pups healthy and to improve the wellness of the beloved breed.

In 2023, Willen learned that NC State was recruiting dogs for a clinical trial testing the efficacy of a dietary supplement on slowing the progression of transitional cell carcinoma, a type of bladder cancer for which Scottish terriers are at particularly high risk. She eagerly signed up her dogs Piper and Tango.

“It’s a win for me, because my dogs are getting additional excellent veterinary care that they wouldn’t otherwise get,” says Willen, who lives in Hendersonville, North Carolina. “And it’s going to help the other breeds of dogs involved in the clinical study, not just Scotties.”

Soon after Willen reached out, that trial’s research team — led by nephrology and urology professor Dr. Shelly Vaden — sent Willen test kits for canine urine samples that would determine her dogs’ eligibility. Piper and Tango turned out to be good candidates and have been visiting NC State every three months since March 2024.

Both dogs receive a daily pill through the clinical trial, though Willen and the study team are blinded to which dog is receiving the actual supplement and which is receiving a placebo. The dogs share an environment and routine, providing a built-in control group for the potential treatment.

Over the course of the trial, researchers found abnormal bladder lining cells in urine samples from 13-year-old Tango and 12-year-old Piper. Veterinarians are monitoring Piper and Tango for progression of urinary disease, though Willen says the dogs are otherwise symptom-free.

Willen is grateful that the study provided insight into her dogs’ health that she never would’ve received otherwise. Every time Piper and Tango visit NC State, they receive a complete abdominal ultrasound that tracks their gastrointestinal health, too.

“Piper and Tango enjoy the extra attention they get while they’re at NC State,” Willen says. “I sure talk to a lot of people about the benefits of being in a clinical trial for the health and well-being of their dog. For me, medical research for well-loved pets is just as important as it is for people.”