A Researcher’s Best Friend: Dogs May Unlock Cancer’s Secrets

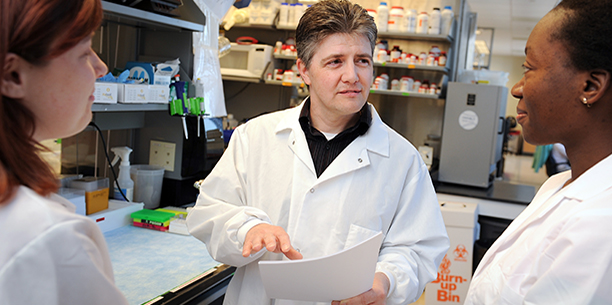

Matthew Breen, a professor of genomics in the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, expects the question and is seldom disappointed.

“Usually in the first few minutes of one of my talks somebody will raise their hand and say, ‘I’m sorry, but you’re saying that dogs get cancer?’, “says Dr. Breen, a member of the NC State Center for Comparative Medicine and the Oscar J. Fletcher Distinguished Professor in Comparative Oncology Genetics.

“The answer, of course, is yes,” says Breen. “Effectively, we and dogs are just differential organizations of the same collection of ancestrally related genes.” Almost a decade ago, Breen showed that characteristic genetic changes in human leukemias were conserved in canine leukemias. Since that time his lab has continued to demonstrate this level of similarity to be the case across a variety of other cancers, suggesting there is a lot to be gained form this comparative approach.

[cvm_video id=”F0RFQnt7YEA”]Watch a video of Breen’s recent presentation “The Role of Clinical Studies for Pets with Naturally Occurring Tumors in Translational Cancer Research” given at a workshop meeting of the Institute of Medicine, a division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. [/cvm_video]

“It is important to recognize that cancers in our pet dog are spontaneous diseases,” continues the genetic researcher. “Our pet dogs live in our homes. They breathe the same air as we, drink the same water, get on our beds and often eat the foods we eat. When we take them for a walk, they encounter the same herbicide, insecticide and pesticide treated grass that we and our children run across. Add to this shared environment the fact that the genome of the dog is 80 to 90 percent similar to that of people, and why wouldn’t dogs and people get the same kinds of cancer?”

A member of a team that decoded the canine genome in 2005, Breen is recognized internationally for his research into molecular cytogenetics—the study of the structure and function of cells and chromosomes—and the comparative medicine application to canine and human cancers.

Breen is a founding member and now serves on the Board of Directors of the Canine Comparative Oncology and Genomics Consortium, Inc. (CCOGC, see CCOGC.net). The CCOGC is a 501c3 national organization that gathers and stores biological specimens from cancer bearing pet dogs,to be used for the advancement of cancer research for humans and canines. He also serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Morris Animal Foundation and is a regular reviewer for the AKC Canine Health Foundation.. Earlier this summer Dr. Breen served as co-editor of a special issue

of the Royal Society’s journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, entitled “Peto’s Paradox and the Promise of Comparative Oncology.

“The dog has been man’s best friend for over 15,000 years,” says Breen. “But the fact remains that in the 21st century, even with lots of new scientific tools to help us understand the cause and progression of cancers, we are still making incremental advancements. I believe the answers to unlocking some of cancer’s most intriguing mysteries about cancer are sitting right beside us. When we look at cancer as an animal problem and not just a human problem, we open the door to numerous comparative opportunities to help accelerate discoveries of new therapies that will benefit ourselves as well as our pets ”